Increasing the maturity of upstream (E&P) supply chain functions

RYAN HAWK AND PETE DOMANKO, PWC, CHICAGO

STEVE WRIGHT, PWC, HOUSTON

Recent declines in the price of oil, along with more than a decade of steeply rising costs in upstream oil and gas, have influenced E&Ps toward more focused and cautious capital spend. Some E&Ps have sought to improve their supply chain management processes as part of a broader effort to increase operational and capital efficiencies. Indeed, the current low-price environment provides an opportunity for Supply Chain functions to communicate and advance the cost efficiencies and overall value they can bring to the larger E&P organization.

Traditionally, E&Ps have been somewhat immature in their Supply Chain management practices, particularly relative to those seen in other industries. Even today, some mid-tier independents operate without a formal procurement organization. But the recognition that "resource plays" are cost-driven plays, coupled with the aforementioned price decline, has many E&Ps looking for efficiencies in that area. Drawing on insights from PwC's 2014 Upstream Procurement/Supply Chain Management Benchmarking Study, which included extensive surveys and in-depth interviews among more than 20 participating E&Ps, this article focuses on what Supply Chain organizations can do now to increase the value they provide to their companies. (For more information on this participants-only industry benchmarking study, please contact the authors.) We begin by outlining some of the constraints under which upstream Supply Chain organizations typically operate, as well as the practices the study found to differentiate good and bad performance-the levers that Supply Chain organizations may consider using to add value.

FACTORS AFFECTING SUPPLY CHAIN ORGANIZATIONS AT E&Ps

Two important trends have had a profound impact on E&P supply chain organizations: (1) a history and culture of business unit or asset autonomy, particularly common among independents; and (2) the strategic shift from international and offshore exploration toward onshore resource play development. The former has resulted in a twofold constraint on Supply Chain organizations. First, control of procurement decisions by asset or region leaders can limit the visibility the Supply Chain organization has into materials management and in some cases even spend. Asset leadership's control over procurement decision-making may limit the ability of the Supply Chain function to deliver value through strategic sourcing. Often this manifests itself in the limited number of spend categories that Supply Chain functions have responsibility for managing. (Although the average Supply Chain organization surveyed by PwC managed about 60% of its company's total third-party spend, the wide range of responses [from a low of five percent to a maximum of 95%] suggests the degree to which E&Ps differ in their opinions about how spend should be managed.)

Second, in the extreme, asset autonomy over materials and services can result in a lack of cross-region standards in processes and data, which in turn can constrain the ability of those companies to leverage the full power of their systems. Many PwC benchmarking study participants suffered from a lack of standard data taxonomy (e.g., over how spend categories are constructed) and managed basic purchase transactions in highly manual fashions. Without the ability to efficiently transact and leverage systems and technology, and lacking the visibility into spend data that would enable cross-region strategic sourcing, Supply Chain organizations may be hard-pressed to sell their services to sometimes-skeptical regional leadership.

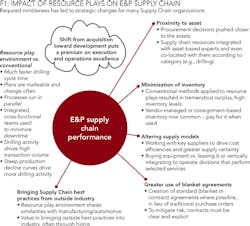

The shift to onshore resource play operations has directed many companies to rethink their approaches to supply chain management. Resource play (unconventional) development differs from the conventional in a host of respects. Most important for Supply Chain organizations, resource plays are often characterized by much faster drilling cycle times, significantly higher transaction volumes, and greater fluidity of plans and rig schedules than are conventional development plays. Because of these characteristics, operators have changed their supply chain approaches in several ways (see Figure 1):

- Relying more on blanket or contract agreements rather than traditional purchase orders. Conventional methods of purchasing simply cannot keep up with the tremendous transaction volume inherent in resource plays.

- Pursuing custom/tailored supply arrangements. Examples include buying equipment as opposed to leasing it or vertically integrating to operate divisions that perform selected services (e.g., self-sourcing proppant, buying rather than leasing truck fleets).

- Minimizing inventory to the extent possible. To establish that they don't overstock supplies like pipe, more resource play operators are using consignment or, to a lesser extent, vendor-managed inventory. The goal of these operators is to pay for materials when they are used, and not until then. On average, companies participating in the PwC benchmarking study reduced inventory values by 15 percent between 2012 and 2014, and several saw reductions of 60% or more over that time period.

- Pushing procurement decisions closer to the assets. Often this means integrating Supply Chain resources with asset-based experts. For example, it is not uncommon for Supply Chain drilling experts to be co-located with an asset drilling team.

In addition, some resource play-intensive E&Ps are now beginning to work with suppliers to help drive costs down and encourage greater supply certainty. In exchange, service companies and suppliers generally require demand forecast information from operators that helps them to make better, timelier decisions on asset and resource utilization. The E&Ps are also recognizing that, with the analogies to the "factory model" found in resource plays, hiring Supply Chain personnel who have experience in manufacturing, automotive or similar fields can yield benefits. More generally, there is increasing recognition that best practices and proven approaches in processes that are endemic to resource plays (e.g., fleet logistics for water hauling trucks) are likely to come from outside the industry.

PERFORMANCE AMONG E&P SUPPLY CHAIN ORGANIZATIONS

The PwC benchmarking study highlighted a number of key performance drivers, some organizational and others focused on key practices.

Organizational

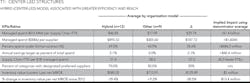

- Hybrid ("center-led") model vs. others. Successful organizations are generally moving toward center-led (hybrid) organizational models for procurement, with careful scrutiny given to the areas that should be centralized. In the hybrid model, most strategic procurement/supply chain management elements are centralized, while their execution is generally decentralized. The often competing goals of customer intimacy, on the one hand, and consistent use of strategic sourcing techniques and stronger visibility, governance and control, on the other, can be met via the hybrid model. The study found that companies using hybrid organizational models had roughly 45 fewer Supply Chain full-time equivalent (FTE) employees, on average, than did those using fully centralized or decentralized approaches. Those companies also witnessed a higher percent of Supply Chain FTE identified as "strategic," higher spend under formal contract, higher annual average cost savings targets, and lower current inventory values (see Table 1).

- Decision-making responsibility for supplier selection-Shared with Supply Chain vs. unilateral business/operations decision. Most E&Ps rely on operations expertise for ultimate authority on supplier selection. But companies where the Supply Chain organization was involved to some degree in the supplier selection decision-in other words, where the decision-making process was shared between Supply Chain and the business-averaged about 1,000 fewer active suppliers than did companies where operations made such decisions unilaterally.

- Sourcing/contracting done centrally vs. regionally or locally. Companies in which most sourcing and contracting was done through a central headquarters location averaged approximately 40 fewer Supply Chain FTE than did those companies whose predominant sourcing method was local or regional.

Practices

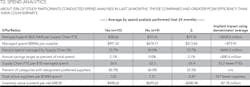

- Spend analytics. Companies that had conducted a formal spend analysis in the previous two years generally had higher managed spend per Supply Chain FTE, higher managed spend per supplier, higher annual average cost savings targets, and lower current inventory values (relative to production) than did their non-analytic peers. At average spend levels, companies conducting spend analysis had 937 fewer active suppliers than did companies that did not conduct such analysis (see Table 2).

- Annual savings target. The companies in the PwC study were about evenly divided between those that maintained a Supply Chain organization cost savings target and those that did not. Having such a goal was associated with higher managed spend per FTE, higher managed spend per supplier, higher percent spend managed by Supply Chain and percent spend under formal contract, lower current inventory values (relative to production), and a higher percentage of Supply Chain headcount identified as "strategic."

- Formal supplier management. Supplier management includes the management of supplier relationships and supplier performance, and may also include the establishment and maintenance of a supplier strategy or framework. Participating companies with formal supplier management programs were leaner in terms of Supply Chain headcount than were companies that lacked such programs. And on average, they had 1,200 fewer suppliers than companies that lacked supplier management programs.

WHAT E&P SUPPLY CHAIN ORGANIZATIONS CAN DO NOW TO ADD VALUE

The previous section examined drivers of performance across companies-factors that most clearly separated good and bad performance of Supply Chain operations. An even more significant study finding is that even the leading E&Ps surveyed have opportunities for improvement in areas ranging from strategic sourcing to materials management to supplier management. Three opportunities that can provide substantial value to their companies are discussed below.

- Increased strategic sourcing and true category management. Expanding the scope of strategic sourcing-both through additional categories and additional geographic scale -is for many E&Ps the most promising short-run value opportunity in supply chain management. If central Supply Chain functions are to deliver more value when commodity prices rebound, it is this area where the growth in resources should be most pronounced.

- Leveraging systems for greater automation. Many participants have systems that are not being fully leveraged for greater automation of purchasing/requisition processes. Others have systems with significant limitations or use spreadsheets or manual methods for specific areas (e.g., material transfers). Two-thirds of participating companies reported some degree of manual effort for every requisition they process. (That is, none of their requisitions was processed in a fully automated fashion.) And none of the independent E&Ps in the study had automated integration with suppliers for acknowledgment of materials received or services provided. The current environment may provide a good opportunity for companies to invest in these capabilities to prepare for the eventual upturn in the cycle.

- Better, cleaner master data. Most participants recognize the importance and power of data analysis, especially spend analytics. In order to leverage that data, however, their data capture, cleansing, storage, governance, and reporting processes need substantial improvements. Once realized, better master data can enable increased strategic sourcing, contract management, transactional efficiency, and overall control over spend, as well as possibly reducing risk for the business.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Ryan Hawk is the lead Partner for the Energy Operations team and has more than 20 years of experience in industry and consulting. Ryan has led numerous consulting projects in oil and gas across upstream, midstream, downstream and oil field services industry segments over the last 10 years.

Pete Domanko leads PwC's Strategic Supply Management capability for the US Energy sector. He focuses on operating model design, category management, purchase-to-pay, contract management, and materials management across the Energy value chain. Industry experience includes Procurement & Supply Chain Management operating model design and implementation, materials management process development, category strategy development, and an end-to-end procurement process transformation.

Steve Wright is the Oil and Gas Benchmarking Lead at PwC. He has more than 25 years of experience in benchmarking and applied research. He has developed and led oil and gas industry studies on cost management, operations, supply chain, finance, and human resources.

PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP is a Delaware limited liability partnership. PwC refers to the US member firm, and may sometimes refer to the PwC network. Each member firm is a separate legal entity. Please see www.pwc.com/structure for further details. This content is for general information purposes only, and should not be used as a substitute for consultation with professional advisors.