Meeting undue demand How price controls are working to outstrip oil supplies

Jason Reimbold

The Theseus Group

Many factors are contributing to the high price of oil–not least of which is government intrusion into free markets in the form of fuel subsidies. Last month, oil prices reached record highs and the governments of several emerging economies were forced to reconsider polices on subsidizing fuel costs. Over the last several years, the world has witnessed a surge in economic growth in developing nations, and the expansion of the global economy has been fueled by immense increases in oil consumption.

The combination of both macroeconomic conditions and market uncertainty has driven the price of oil to all-time highs, but surging prices are having little effect on demand in many emerging economies.

A number of developing nations such as China, India, and Indonesia have sustained marked economic growth despite rising energy costs by heavily subsidizing fuel costs, and this cost is becoming more difficult to absorb. In fact, Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Sri Lanka have recently reduced subsidies or have announced plans for near-term reductions. However, it is unlikely these reduced subsidies will have a significant impact on global demand without price increases in China.

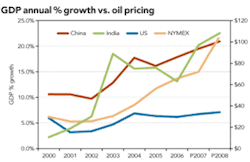

The Chinese government has not announced a reduction in fuel subsidies since a 9% price hike in November 2007. By capping fuel costs, China (the world’s second largest oil consumer) is spurring continued consumption despite spiking oil prices. Currently, China is paying approximately 60% less at the pump than consumers in the US due to fuel subsidies. This means the Chinese economy can continue to grow on ~$80 oil while non-subsidized economies struggle to achieve growth at $120+ per barrel.

Since 2000, nations with fuel subsidies have been able to sustain double digit economic growth in tandem with rising oil prices as nations without price controls, namely the United States, exhibit relatively flat GDP growth.

Anti-inflation and economic stimulus are the primary reasons cited as the justification of implementing price controls for fuel in emerging economies, but these controls may not be as helpful to the impoverished citizens of developing societies as it may appear.

In late 2006, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) published a study on the effects of fuel subsidies. Its research indicated that subsidies were a relatively ineffective instrument for aiding the impoverished. In fact, the report suggests that the richest 60% of households accrue up to 85% of the subsidy benefits.

Of course, this unequal distribution of benefits is because the wealthiest citizens are the largest consumers. Nevertheless, fuel subsidies remain a popular political tool, and any attempt to reduce subsidies in emerging economies will seldom go unchallenged.

Civil upheavals, some violent, have occurred in the past when there was a threat of price increases for fuel. Most recently, India and Indonesia have experienced vast anti-government demonstrations on the news of subsidy reductions. Once implemented, these inefficient policies are difficult to reverse. Therefore, oil producers must struggle to meet undue demand.

Classic economic theory suggests that as price increases demand should fall proportionately, but demand destruction is not allowed to occur in an environment of price controls. Thus, the free market mechanism for controlling prices is unable to work–as we are witnessing in the global oil market. Of course, there will never be a truly free market for oil, but less intrusive political policies would help to alleviate the effects of demand manipulation.

As long as fuel subsidization continues to be a governmental policy in developing nations, the global demand for oil should continue to be strong despite record prices.

About the author

Jason Reimbold is vice president of The Theseus Group (www.thetheseusgroup.com), an energy M&A consulting firm based in Tulsa, Okla. In 2005, Reimbold founded www.GlobalOilWatch.com, an energy research portal for industry analysts and investors. In 2007, he co-authored The Braking Point: America’s Energy Dreams and Global Economic Realities (www.thebrakingpoint.com) with Mark A. Stansberry.