Avoiding Gambler’s Stalemate: strategies for investing in petroleum ventures

Rick Box Hunt Petroleum Corp. Houston

Investing in petroleum ventures is like playing blackjack: too much risk yields spectacular defeat, while too little risk yields unspectacular defeat. This article is intended to provide a simple, cost-effective method for steering for the narrow sweet spot in-between.

Terminology

Three basic results are possible from a series of gambles:

- Gambler’s Ruin – The capital allocated to the venture is lost, and no more gambling is possible

- Gambler’s Victory – The objectives of the gambling (whatever they may be for a particular investor or set of investors) are met1

- Gambler’s Stalemate – An alternating series of small wins and small losses result in little overall net gain or loss; time is lost, and possibly with it the opportunity.

Very little has been published about Gambler’s Stalemate, yet it is a vital part of the investor’s strategy. In fact, the objective of the investor can be usefully summarized as, “To invest in such a way that Gambler’s Ruin is unlikely, and the chances of Gambler’s Victory compared to the chances of Gambler’s Stalemate are acceptably favorable.”

The major purpose of this article, therefore, is to explore some strategies that might improve the chance of recognizing and avoiding Gambler’s Stalemate.

Gamble size is proportional to Stake

We are most interested in companies who follow a “proportional-risk strategy,” which means that their amount invested in a particular opportunity is directly important to the “Stake,” the value of the company. Most companies follow this strategy. Bigger companies take on bigger ventures to achieve equivalent percentagewise effects.

One corollary is: any company’s optimal amount to invest in each venture is proportional to that company’s available capital2; as their success or failure produces growth or shrinkage, the optimal amount invested will grow or shrink proportionally. Mathematically, this means (see Equation 1) that investment is a function of the probability of success of the venture, the reward expected, and of time.

Equation 1: Investment(Ps,Ret,t) = PIET(Ps,Ret) * Stake(t)

Where t = time;

Ps = Probability of success;

Ret = Return (expected NTIR3)

Stake = The amount of money available for investment;

And PIET = Percentage Invested Each Time, the fractional amount of the Stake that is invested.

Obviously Stake is a function of time, because successful gambles will grow the company, and unsuccessful ones with shrink it. The question is: exactly how does PIET depend on Ps and Ret?4

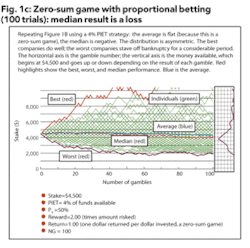

Zero-sum game with Proportional Betting: median result is a loss

One thing to be aware of before designing an investment strategy is the bias inherent in any PIET method.

The clearest way to illustrate this is to model a very simple series of zero-sum coin-flips where the PIET is fixed (in this case at 20%). In Figure 1A, we have a typical result for two companies after two gambles each. The first company began with $5,000, risked 20% (i.e., $1,000) in their first gamble, and lost.

In their second gamble, 20% of their remaining $4,000 (i.e., $800) was risked, resulting in a victory, bringing their money up to $4,800. The second company also began with $5,000; the first gamble ($1,000 risked) won, bringing their money up to $6,000, then 20% of that (i.e. $1,200) was gambled and lost, bringing their result down to $4,800.

After one win and one loss in either order, companies have lost the same amount of money. This result may seem unexpected5: after a 50-50 result in a fair game, both gamblers have lost 4% of their initial stake. There would seem to be a bias in favor of “The House,” like negative-sum games have. This PRB (“Proportional-Risk Bias”) is worth investigating more deeply.

Zero-sum game with Fixed Betting: median result is a tie

In Figure 1B, we model the scenario where 101 companies each begin with $4,500, and play 100 sequential gambles of a fixed $180 each.

As expected, the result is a random-walk around $4,500. In red, the best, worst, and median results are highlighted. The best and worst results move symmetrically away from the median, which is flat. The average result, shown in blue, is also flat (a requirement of zero-sum games). Only the worst company went bankrupt. The histogram is symmetric around $4500.

There is no PRB here, because the gambles are fixed at $180, not proportional to Stake.

Zero-sum game with Proportional Betting: many gamblers and many trials

In Figure 1C, for comparison, we model the scenario where 101 companies each begin with $4,500, and play 100 sequential gambles of a proportional 4% each. Initially the investment is 4% of $4,500, or $180, which is identical to Figure 1B, but after the first gamble it will float up or down with success or failure.

The median value trends downward, but the average trend is flat. The best case goes up more steeply than the worst case goes down. The histogram is asymmetric (“skewed to the left”). The good news (from the gambler’s standpoint) is:

- If a losing streak happens, the player responds by gambling less, making bankruptcy theoretically impossible6 and practically rare.

- If a winning streak happens, the player responds by gambling more, making big success quite possible.

The bad news:

- If neither good nor bad luck happens, and the winning percentage remains around 50% at all times, the player experiences a slow diminution in funds: Gambler’s Stalemate with a negative bias (PRB as seen in Figure 1A) built in.

Unlike gambling addicts, who might raise their bets to try and recover from a losing streak, a responsible company following the proportional-risk strategy will reduce their bets, making Gambler’s Ruin unlikely. Another way of looking at this is that the company has no memory: each gamble is treated as the start of a brand new scenario – the current level of funds available determines the current optimal amount to be risked.

In the event of a hot streak, the company will grow, so its amount risked will grow proportionally, but euphoria will not be allowed to raise it more. As with any proportional-gambling strategy, the median case will inevitably suffer from a negative bias (PRB).

In summary, proportional betting in a zero-sum game yields an asymmetrical distribution of outcomes compared to fixed-amount gambling: victory is enhanced; ruin is mitigated; median cases are somewhat diminished, and are lower than the average.

Biased perceptions

The political implications of this are huge. Imagine if a hundred or more oil companies were engaged in strategies similar to that of Figure 1C. More companies would lose money than make money (because the median is negative), so people down at the Petroleum Club would be crying about the industry being in yet another drought, needing tax breaks or better technology to avoid closing down. Workers would fear losing their jobs.

The net average profit of all companies would be zero (because the average is flat), so bankers would be very hesitant to lend money to the industry, and stock gurus would advise investing in a more robust industry. The best one or two companies would experience record profits and massive growth (because the best case is excellent), which they would struggle to manage without great dislocation in their methods. The media would give disproportionate coverage to these bonanzas. The public would learn about their conspicuous success and cry out for oil companies to be taxed or nationalized.

This is a pretty accurate description of the status of the oil industry most of the time. The statistical benefits of the proportional-risk strategy are so important that every company must adopt something similar even though the political consequences for the industry as a whole can be very negative. Much of the unpopularity of the oil industry with the public is explained by this asymmetry.

Positive-sum game

To introduce our methodology in its clearest form, the previous simulations were oversimplified in three main ways:

- No company in any industry would ever knowingly engage in zero-sum gambling: if there is no net profit to be had, why bother?

- Typical Ps for petroleum ventures is less than 50%, ranging from 5% to 40%, with 15% to 20% being common.

- Gambling is not a perfect analogy to petroleum investing in several ways. Most importantly, there is a lag involved in receiving money after successful gambles. To some extent this can be corrected using various time-value-of-money techniques. Also, gambles can happen simultaneously, violating the mathematical assumptions used here. These issues are touched upon later in this paper.

Next, let’s next see how factoring in the first two of these three effects make the PRB asymmetry even worse.

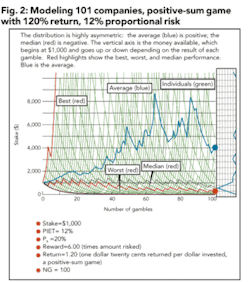

In Figure 2, we model the scenario where 101 companies each begin with $1,000, and play 100 sequential 20% Ps gambles of a proportional 12% each. For the first time, the situation favors the players: $1.20 expected return per $1.00 invested. However, the chances of success are far lower, making the down-side risk more dangerous.

The average (blue line) grows7, as expected8, but the median (center red line) still declines somewhat. The best result (upper red line) grows rapidly; the worst result (lower red line) falls dramatically to a very low number. The histogram is extremely skewed to the left, emphasizing that most companies lose money, while a very few do extremely well.

The political implications of this are similar to those for Figure 1C, but more so. More companies would lose money than make money, so people at the Petroleum Club would be crying for relief. Many companies would fold. Workers who hadn’t yet lost their jobs would be in fear. The net average of all companies would be profitable, so bankers would be somewhat willing to lend money to the industry, and stock gurus might cautiously invest. The best several companies would experience record profits and massive growth, which they would struggle to manage without great dislocation in their methods. The public would learn about their conspicuous success and cry out for oil companies to be taxed or nationalized.

Simulation strategy

If a company has embarked on a proportional-risk strategy, and finds a venture of a certain Ps available, what percentage should they invest? In other words, how does optimal PIET depend on Ps?

A good approach is to forward-model each possible PIET value then compare results. For the case where PIET=12%, Figure 2 is the modeled result: but was 12% the best figure? From the right edge of the diagram, the final median (central red line) value of around $300, and the final average (blue line) value of around $4,000 are saved in a table. If this is repeated for PIET values ranging from 0% to 50%, and the two curves plotted against PIET, we arrive at Figure 3A. The red and blue dots representing the endpoints of Figure 2 are not perfectly met, because of the randomness involved in repeated trials. Figure 3A displays the results after 100 trials of each PIET value.

To optimize the median result requires PIET to be around 5%; to optimize the average result requires PIET to be around 20%: so what do we want to optimize?

Hybrid measurement

One crucial aspect of proportional gambling is the downward bias in the median. In practical terms, this means that in these environments, a healthy company will lose money in most years. Statisticians may be comfortable with this, willing to recommend riding a long string of mediocre-to-losing years, waiting for that one hugely successful year to arrive, but what if the investors are not so patient?

Each investor will have differing objectives, so there is no universal answer to the question of what measure to optimize. However, it should be possible in the case of any given investor to find their particular answer.

Suppose for example that our particular investor (whether individual or corporate) is rather typical, and says things such as:

- “The best-case results are alluring, but the romance of a 99th-percentile result should be more or less ignored in planning; if it happens, wonderful.”

- “The worst-case results are alarming; but 0th-percentile result should also be ignored.”

- “Our average-case result is important, because it is driven by the upside possibilities we so crave.”

- “Our median-case result is even more important: about twice as important as the average, because our particular investors demand a certain routine level of success.”

From these answers a metric can be devised.

Equation 2:

Hybrid = (Median2 * Average)1/3

This is nothing more than the geometric average of the median twice with the average once. The “Hybrid” function has been displayed in black on Figures 2 and 3A. It tracks closer to the median than to the average. Other Hybrid functions, incorporating the 20th Percentile result, or chances of losing money, or various other statistics, could be devised to represent any investor’s suite of motives.

Once a suitable Hybrid function is found, the problem becomes to locate its maximum.

Example of optimization

If Return=1.20 and Ps =20%, what is the optimum PIET strategy for the above investor? As shown in Figure 3A:

- Investing 3% to 5% would optimize our median performance, but offer little chance of big success, as seen by the fact that the average result is below $3,000 there: This would commit the company to rather pedestrian results, so it is probably too conservative. The Hybrid curve is not optimized.

- Investing 12% to 28% would make average performance soar off the charts, but offers a median performance around $0: This would make it likely that we would go bankrupt, unless we got lucky enough to hit it big, so it is probably too risky. The Hybrid curve is not optimized.

- Investing 6% to 9% would probably be best for the investor interviewed above, because his Hybrid measure is maximized there. This offers a performance that is likely to be better than $1,000 (based on the red median curve), with good possibilities of 6- to 10-fold return or better (based on the average curve).

Given that the black Hybrid curve is not smooth, where is its true maximum? The jitter gives us a feel for the randomness of the underlying process, but complicates the optimization process9. Perhaps more companies could be put into the simulation, to blend this out. Perhaps a longer time frame (i.e., greater NG) should be studied. Figure 3B is a re-run of Figure 3A, using an incremental PIET of 0.002, giving a denser horizontal sampling and a zoomed-in view: this helps, but the optimum is still difficult to locate precisely.

These are complexities which will not be fully explored here, though they are interesting, and narrowing down this range is obviously vital to the investor. For now, let’s assume that the investor is comfortable with using Figure 3B to decide that an optimum PIET is about 7% for this example, and move on to the next vital question: How does PIET vary when Ps and Return change?

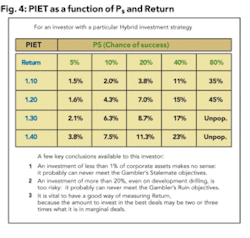

Overall optimization

If the analysis shown in Figure 3A and 3B is repeated for various values of Return and Ps, most of the cells in Figure 4 can be populated10. The cells in the lower right cannot be populated, because low-risk gambles that return a sizeable multiple of the investment do not exist in the real world. If they did, they could not be modeled by this method, and do not need to be, for the optimal strategy is clear: run, do not walk, to invest immediately, without further analysis. Get there before the competition does. Read the rest of this article after you are wealthy.

The values in Figure 4 are useful, though they only apply precisely to the investor whose Hybrid function was optimized. They remind us that where margins are tight (Return<1.20) and risk is high (Ps <20%), care must be taken to invest a rather small proportion (PIET < 5%) of the company assets on any given venture. This is where the typical oil company finds itself. Many ventures, especially those in deep water or remote locations, cost more than any single company could afford in light of their PIET restrictions: this explains why even the super-major oil companies bring in rival firms to partner with them on their most attractive prospects. It is evidence of responsible caution, not of collusion.

On the other hand, when some companies perform the exercise of defining their investment strategy and a metric to measure it with (such as the Hybrid function shown here), then perform PIET optimization (such as in Figure 4), they are surprised to find that their typical historical investment has been significantly less than the optimum amount. They inhabit the left portion of Figure 3 where the median is high but the average is not. They have resigned themselves unknowingly to Gambler’s Stalemate. A very simple analysis of the type done in this paper, allows them to re-energize their future.

Consideration of Figure 4 leads people to make bolder resolutions, such as, “We should never again fear to invest more than 1% of our corporate assets into any venture.”

Simultaneous investment

In Figure 3B, the Hybrid curve is low to the left of about 5% PIET. This happens because the gambler has more than 95% of his funds idle at any given time. The same would not usually be true of petroleum investors: the funds would be simultaneously invested, not sequentially. This has not been modeled here, for it complicates the mathematics severely without adding much understanding.

Investing in several small deals simultaneously would have the effect of filling in the part of the Hybrid curve left of its apex. In the extreme case where all money is reinvested continually, the Hybrid curve could be completely filled, and would be flat from the apex shown here to the y-axis. The investor could then say, for example, “Your curve shows that a 6% PIET is optimum, but if I did 2% PIET on three times as many investments, the result would be the same.” To which we would reply, “They would both avoid Gambler’s Ruin, and they might offer similar average results, but there is more upside romance in the 6% strategy, and it involves one third as much work. Moving to the left of the optimal PIET would not be as bad as the graphs here show, but still is not recommended.”

Summary

Running a program that simulates sequential gambles with instantaneous reward can give good insight into the petroleum investor’s problem, even though it involves simultaneous gambles with longer-term payouts – though care must be taken to consider the time-value-of-money issues, and the effects of simultaneous investing.

The method employed here consists of:

- Determine a set of mathematical objectives representing investor goals

- Determine the relative weights of each objective

- Generate a Hybrid investment function (a weighted average of the objectives)

- For each value of Ps and Return, select a range of possible PIET strategies; for each strategy, run forward models to simulate many companies, computing the best, worst, median, and average results, and blending them to calculate the Hybrid function.Select the PIET value that optimizes the Hybrid function.

Conclusions

Petroleum investing can be modeled as a sequence of gambles. For each gamble, the optimal amount to be risked depends on the chance of success, but is also proportional to the stake available for investment. A proportional-risk strategy is therefore probably best, although it contains asymmetries that are important for the investor and carry with them negative political consequences.

The public will usually focus on the most successful companies at any time, and be jealous of their success, while industry workers, market analysts, and banks will focus on the median performance, which may be underwhelming or worse. Investors need to consider both average and median results, in order to take a careful look at which proportional-risk strategy to employ: too much aggressiveness will imply almost certain decline in net worth and will risk Gambler’s Ruin; too much conservatism condemns them to run on a treadmill with little chance of big rewards (“Gambler’s Stalemate”). Between these lies a narrow sweet-spot, which may be located by proportional-risk modeling.

About the author

Rick Box [[email protected]]earned a bachelor’s and two masters’ degrees from the Mo. U. of Science and Technology. He has worked in the petroleum industry for 30 years as a geophysicist with particular interest in tying well data to seismic data. He returns to his mathematical roots occasionally, writing papers on economics, statistics, or computer sort algorithms.

- In other words, the capital yields a satisfactory return.

- Because “Company X” may in fact be “Company Y,” the same company at a later date. What is true for separate companies at the same date is true for one company at different dates.

- This would normally be Undiscounted Cash Flow divided by Investment, though other methods of accounting are also valid.

- We purposely simplify here by ignoring the fact that in the petroleum business the gambles are not always sequential, but may be overlapping. A company may be required to decide how much to invest in Venture #209 when the results of Venture #208 are unknown. This does not invalidate the results that follow here, but it means that there is a time lag that is not accounted for. See the “Simultaneous Investment” section.

- Many people believe that this cannot be true of a zero-sum game, but it can.

- Of course if there were a company reduced to pathetically gambling fractions of a penny, it would not be viable in practice, though not technically considered bankrupt by the mathematics.

- In line with the expected growth of 2.4% (investing 12% at a 20% return)

- Depending on the time-frames involved, and other factors, this might be a more attractive ROR than that offered by almost any other industry.

- This instability is caused by the large instability in the Average curve. Since Hybrid is the cube root of the median (a smooth function) times itself (smooth) times average (highly unstable), Hybrid will be somewhat unstable by its nature.

- When Return=1.20 and PS=20%, the optimum PIET=7%, as we learned in the previous section