Using like-kind exchanges to optimize tax benefits for O&G property, equipment

Kelly Alton, NES Financial Corp., San Jose, Calif.

The capital-intensive nature of companies engaged in oil and gas operations and the liberal rules that determine the like-kind nature of oil and gas properties combine to make IRC Section 1031 like-kind exchanges very attractive to oil and gas companies. Although Section 1031 requires an “exchange,” which suggests an unmonetized reciprocal transfer of property, the vast majority of like-kind exchanges are structured simply as a sale of a property to one person followed by a purchase of property from another person and the exchange element is supplied by the participation of a qualified intermediary (QI) which, from a tax perspective only, serves as the person with whom the exchanger actually does the exchange.

This opens up a vast array of dispositions and acquisitions that may be structured as a like-kind exchange.

Tax benefits of a like-kind exchange

The tax benefits of an exchange are considerable: all of the gain (including depreciation and depletion recapture) that would otherwise be recognized currently on the sale is deferred until such time as the replacement property acquired is sold in a taxable transaction. The “cost” of these benefits is the carryover basis rule. The replacement property uses the basis of the relinquished property, increased by net cash paid or non-like-kind property transferred and any gain recognized. This rule creates a further incentive for an exchanger to exchange the replacement property in future like-kind exchanges, which has the potential to make the tax deferral benefit permanent.

At current federal income tax rates, this translates into a potential tax savings of 35% for corporations and 39.6% for partnerships and individuals, plus state tax savings, which can be significant depending upon the state. Money not paid in the form of taxes to the federal or state government can be used in the exchanger’s business, resulting in a greater return on capital.

Generally, the types of assets most suitable for a like-kind exchange are those with a high residual value and a low basis relative to current fair market value, either through appreciation in value or by taking depreciation or depletion deductions. To achieve the full tax benefits of the like-kind exchange, the exchanger must invest at least the full equity of the relinquished properties into the replacement properties and the replacement properties must also be equal or greater in value to the relinquished properties. An exchanger may add its own cash to the exchange in order to “trade up” to a better property, or may acquire one replacement property in exchange for several relinquished properties, or vice versa.

Tax benefits are also available where the exchanger is unable to acquire enough property to defer all of the gain, which could occur if a deal falls through. If the exchange “fails” in the following taxable year, the sale is treated as an installment sale and the gain is deferred to the year in which the exchange fails. This generally creates a one-year tax deferral, subject to a possible interest charge on the deferred tax liability.

What is like kind?

The crux of the like-kind exchange rules is the like-kind standard, which determines whether the properties can be exchanged tax-free. This is the first step in deciding whether a like-kind exchange is feasible. The like-kind standard breaks down into three rules based upon the type of property being exchanged: real property, personal property, and intangibles. By personal property, the IRS means tangible depreciable property that is not real property, which in the business context is capital equipment.

The real property rule is the most liberal of the three rules. Almost all real property is considered like-kind to other real property for Section 1031 purposes. Thus, unimproved real estate is like-kind to improved real estate, and many mineral interests, such as oil leases and overriding oil and gas royalties, due to their status as real property under state law are considered like-kind to other types of real estate. For example, an office building may be exchanged for an oil lease, a tract of vacant land, a farm, or even supply contracts that are tied to specific mineral deposits.

The personal property rule is less liberal than the real estate rule, but it is still flexible enough to offer many opportunities for exchanges. Personal property must either be like-kind or like-class to qualify for a like-kind exchange. The IRS has provided definitive guidelines for the like-class rule, which piggyback on the North American Industry Classification System and the general asset classes (GAC) used for tax depreciation. All properties included within a NAICS 6-digit class or a GAC are considered like-class. Notwithstanding its inclusion in a NAICS class, if the equipment is considered a fixture under state law, then it would be considered real property.

Oil and gas related production and transportation equipment would generally be included in one of the following classes:

- NAICS 333132, which covers oil and gas derricks, drilling rigs, drilling machinery and equipment, rock drill bits and Christmas tree assemblies;

- NAICS 333120, which covers all manner of heavy construction equipment;

- NAICS 333911, which covers oil well and oil field pumps; and

- NAICS 336611, which covers floating oil and gas drilling and production platforms, barges, cargo ships, container ships, towboats, tugboats and other marine vessels.

Although this system may seem rigid, in practice it is often very beneficial because any property described in a given class is considered like-class to any other property listed in that class no matter how different they may seem. The system provides a safe harbor for taxpayers, which means that an IRS agent generally will not second guess the taxpayer about whether the exchanged properties meet the like-class requirement.

The intangibles rule is the least flexible and requires that both the rights involved in, as well as the property underlying, the intangible be like-kind. Although goodwill, going concern value, partnership interests, and liquid assets, such as stocks and bonds, are excluded from Section 1031, most other types of intangibles, such as patents, permits, licenses, processes, and designs, can be exchanged.

However, even if the properties are like-kind or like-class, the locations of the properties may change that status to non-like-kind. Real property located in the United States is not like-kind to real property located outside the United States. Personal property is subject to a similar rule which looks to where the property has been used or will be used, rather than its location, which may change over time. Special rules allow transportation equipment operated to and from the US and equipment used in offshore production activities to be treated as US property.

Like-kind exchange structures

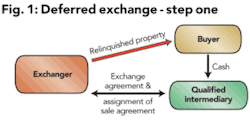

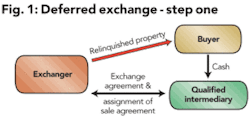

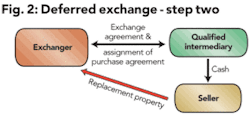

Once it has been determined that the properties are like-kind, the exchanger must then decide how to structure the exchange. Most like-kind exchanges are “deferred exchanges” where there is a gap in time between the sale and the purchase. In a deferred exchange, the exchanger has 45 days after the sale of its property (relinquished property) to identify like-kind replacement property and must acquire the identified replacement property within 180 days after the sale of the relinquished property. In order to create the exchange, the exchanger must enter into an exchange agreement with the QI and assign its rights, but not its obligations, in the sale agreement to the QI prior to the sale.

Conversely, on the purchase leg of the exchange, the exchanger assigns its rights, but not its obligations, in the purchase agreement to the QI prior to the purchase. In both legs, the other parties to each contract are notified of the assignment to the QI. Otherwise, the sale and the purchase both proceed in essentially the same manner as they would have in the absence of the exchange.

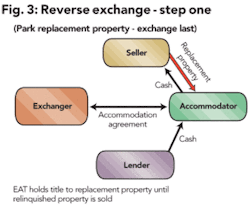

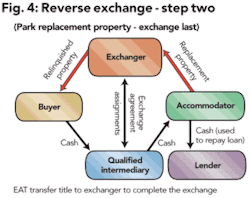

So-called “reverse exchanges” are also possible where an exchange accommodator, usually a wholly owned subsidiary of a QI, holds (“parks”) the replacement property prior to the sale of the relinquished property so that the replacement property can later be transferred to the exchanger (Exchange Last) or parks the relinquished property after the exchange for subsequent sale to an unrelated buyer (Exchange First).

A deferred exchange can also be structured in conjunction with a reverse exchange so that some of the replacement property can be obtained and parked before the sale of the relinquished property, while the rest of the replacement property can be acquired after the sale of the relinquished property.

A like-kind exchange involving multiple assets or multiple types of assets, such as real estate and personal property or a business unit, will be segregated into exchange groups where each group consists of all the properties that are like-kind or like-class. The basis and gain computation rules are then applied to each exchange group.

Conclusion

Companies should always consider whether a like-kind exchange is feasible when planning sales and acquisitions of property and equipment because of the significant tax benefits and minimal changes to the buying and selling processes.

About the author

Kelly Alton [[email protected]] is general counsel of NES Financial Corp., a qualified intermediary in San Jose, Calif. Her practice is focused exclusively on Section 1031 like-kind exchanges. Alton holds a JD from Harvard Law School and a BA in mathematics from Boston University.

Bibliography

Author, with Bradley T. Borden, “Section 1031 Alchemy: Transforming Personal Tangible and Intangible Property into Real Property,” Real Estate Taxation, Vol. 24, No. 2 (1st Quarter 2007)

Author, with Louis S. Weller, “New IRS Ruling Unveils Restrictive Approach to Like-Kind Exchanges of Intangibles,” Journal of Taxation, Vol. 104, No. 4 (April 2006)

Author, with Bradley T. Borden and Alan S. Lederman, “Rev. Proc. 2004-51: The IRS Strikes Back,” Taxes, Vol. 83, No. 2 (February 2005)

Author, “Personal Property Like-Kind Exchange Update: New NAICS Product Classes,” Journal of Taxation, Vol. 101, No. 5 (November 2004)

Author, with Louis S. Weller, “Does State Law Really Determine Whether Property is Real Estate for Section 1031 Purposes?” Real Estate Taxation, Vol. 32, No.1 (4th Quarter 2004)