Bridging valuation gaps for undeveloped and unproven reserves

Donald Erickson and Bryce Erickson, Erickson Partners LLC, Dallas

Valuations of petroleum reserves can often be relatively straightforward. The petroleum industry was one of the first major industries to widely adopt the discounted cash flow (DCF) method to value assets and projects — in particular oil and gas reserves. These techniques are generally accepted and well understood in oil and gas circles to provide reasonable and accurate appraisals of hydrocarbon reserves. However, when market, operational or geological uncertainties become challenging, such as today's low gas price environment, sometimes the DCF can break down in light of marketplace realities and "gaps" in perceived values can appear.

Whereas DCF techniques are generally reliable for proven developed reserves (PDP's), they do not always capture many uncertainties and opportunities associated with the proven undeveloped reserves (PUD's). The same is true of the less certain upside in the probable and possible (P2 & P3) categories. In fact, the DCF's present value mathematics many times discourages investment at low ends of pricing cycles. However, the reality of the marketplace is often not nearly as clear. In fact, it can be downright murky. In these scenarios, one potentially useful method to is the use of option theory to help pricing of these assets.

In past periods, one of the practical ways sophisticated acquirers accounted for upside or uncertainty attributable to these reserve categories was to reduce expected returns from an industry weighted average cost of capital (WACC) or apply a judgmental reserve adjustment factor (RAF) used to downward adjust reserves for risk, typically expressed as a percentage. This technique effectively increased the otherwise negative DCF value for an asset or project's upside associated with the PUD's and unproven reserves.

At times market conditions can require buyers and sellers to reconsider methods used to evaluate and price an asset differently than in the past. In our opinion, such a time currently exists in the pricing cycle of natural gas (NG) reserves; and in particular application to the PUD's and even to unproven reserves. The rationale for this thinking is impacted by NG's current low historical price levels; and in light of this price, coupled with the forecasted NYMEX price deck, many, if not most PUD's appear to have a negative DCF value. If one solely relied on the direct DCF income approach much of these reserves would be deemed worthless.

The reality is that in actual market transactions, PUD's and unproven reserves still hold value and sometimes significant value. If one firmly believed in (i) the accuracy of current NYMEX forecasted natural gas prices, and (ii) the outlook for supply, an acquirer might desire to pay very little or nothing for these PUD's and unproven reserves. Yet value remains. A highlighted example of this is Chesapeake's recent dispositions of acreage assets in shale plays.

Chesapeake is not alone in indicating to the marketplace that it is undesirable to drill in many shale areas at sub $6.00 gas prices. However they have been able to generate substantial marketplace value for its holdings. Why then and under what circumstances might they have significant value?

The answer lies within the optionality of a property's future DCF values. In particular, if the acquirer has a long time to drill, one of two forces come into play: either (i) the current price outlook can change radically for a resource and suddenly the PUD's or (ii) drilling technology can change, such as the onslaught of hydraulic fracturing, and the unproven reserves accrue significant DCF value.

This optionality premium or valuation increment is typically most pronounced in unconventional resource play reserves such as coal bed methane gas, heavy oil, or foreign reserves; or, additionally when the PUD's and unproven reserves are held by production. These types of reserves do not require investment within a fixed short timeframe.

Current pricing environment: challenge = opportunity

One of the primary challenges for industry participants when valuing and pricing oil and gas reserves is addressing PUD's and unproven reserves. After the major recession starting at the end of 2007 and continuing in 2008 and 2009, some PUD's dropped from value levels as high as 75% RAF's of proven developed producing pricing to 20% RAF's or less. Fortunately for today's sellers, these RAF's have bounced back to much higher levels in late 2010 and into 2011 for certain types of reserves.

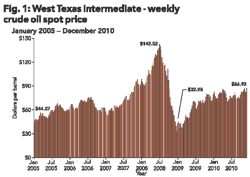

This price level recovery for PUD's is partly attributable to the recovery in the US and global economy and partly due to increases in the price of oil. Oil prices had dropped from $142.52 in July 2008 to $32.98 by the end of 2008. Since then, prices have climbed to above $90 a barrel in early 2011 as shown in Figure 1.

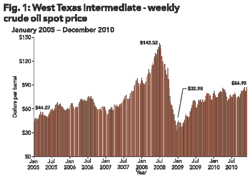

Natural gas prices, on the other hand, peaked at $11.32 an MCF in the summer of 2008 and have dropped to near $4.00 an MCF in early 2011. Worse yet, the outlook for natural gas as evidenced by the NYMEX strip prices to 2015 shows very little increase. These low prices are heavily influenced by the unprecedented successes that the natural gas drillers have had in the shale plays through the continental United States — significantly increasing supply in the United States. See Figure 2.

As previously mentioned, PUD's are typically valued using the same DCF model as proven producing reserves after adding in an estimate for the capital costs (capital expenditures) to drill. Then the pricing level is adjusted for the incremental risk and the uncertainty of drilling success, i.e., commercial volumes, life and risk of excessive water volumes, etc. This incremental risk could be accounted for with a higher discount rate in the DCF or with a RAF or haircut. Currently with the historically low natural gas prices, many times a raw DCF would suggest little or no value for the PUD's or unproven reserves. Interestingly, market transactions with similar reserves (i.e., with little or no proven producing reserves) have demonstrated significant amounts attributable to non-producing reserves demonstrating the marketplace's recognition of this optionality upside.

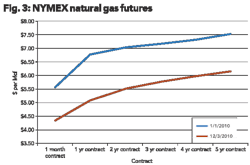

Studies have shown that NYMEX futures are not a very accurate predictor of the future and buyers are estimating the value of this option into the prices they are willing to pay. When NYMEX forecasts $4.00 an MCF it could actually be $8.00 when that future date rolls around.

So what actions do acquirers take when values are out of the money in terms of drilling economic wells? Why do acquirers still pay for the non-producing and seemingly unprofitable acreage? Experienced dealmakers realize that the NYMEX future projections amount to informed speculation by analysts and economists which many times vary widely from actual results. Note in Figure 3 how much the future forecasted prices changed in only one year.

Real options - valuation framework

In practice, undeveloped acreage ownership functions as an option for reserve owners and an option pricing model can be a realistic way to guide a prospective acquirer or valuation expert to the appropriate segment of market pricing for undeveloped acreage. This is especially true at the bottom of the historic pricing range occurring for the NG commodity currently.

This technique is not a new concept. Several papers have been written on this premise. Articles on this subject have been written as far back as 1988 or perhaps further. Other articles and papers have been presented at international seminars.

The PUD and unproved valuation model is typically seen as an adaptation of the Black Scholes option model. An applicability signal for this method is when the owners of the PUD's have the opportunity but not the requirement to drill the PUD and unproven wells and the time periods are long, i.e. five to 10 years. The value of the PUD's therefore includes both a DCF value, if applicable, plus the optionality of the upside driven by potentially higher future commodity prices and other factors. The comparative inputs, viewed as a real option, are shown in Table 1.

Pitfalls and fine print

There are, of course, key differences in PUD optionality and stock options as well as limitations to the model. Amid its usefulness, the model can be challenging to implement. Below are some areas in particular where keen rigorous analysis can be critical:

- Observable market - Unlike a common stock, there is no direct observable market price for PUD's. The inherent value of a PUD is the present value of a series of cash flows or market pricing for proven reserves, if available. All commodity prices are volatile but natural gas prices are more volatile than most, since they have both year to year supply and demand changes in addition to significant seasonal swings.

- Risk quantification — We have found that oil and gas price volatility benchmarks (such as long term index volatilities) are not all-encompassing risk proxies when valuing specific oil & gas assets. If not analyzed carefully the model can sometimes have trouble capturing some critical production profile and geologic risks that could affect future cash flow streams considerably. Risks can include items such as (i) production profile assumptions, (ii) acreage spacing, (iii) localized pricing versus a benchmark (such as Henry Hub or West Texas Intermediate Crude), and (iv) statistical "tail risk" in the assumed distribution of price movements.

- Sensitivity to capital expenditure assumptions — Underlying analysis of an asset or project's economics can present particular sensitivity to assumed capital expenditure costs. In assessing capital expenditure's role as both (i) a cash flow input and (ii) an option model input, estimations of future costs can be a very acute yet challenging assumption to properly measure.

- Time to expiration — This input can require granular analysis of field production life estimates coupled with expiring acreage, then filtered within the drilling plans of an operator. The resulting weighted time estimate can present problems with assumption certainty.

The availability of drilling resources tends to decline while the cost of drilling and oilfield services tend to rise, often precipitously, when oil and gas prices rise. These factors can present an oscillating delta in both cost and timing uncertainties as the marketplace responds by investing capital into undeveloped reserves while the "fuse burns" on existing lease rights. The time value of an option can increase significantly if (i) the mineral rights are owned, (ii) unconventional resource play reserves are included, (iii) foreign reserves, or (iv) reserves held by production. In these instances the PUD and unproved reserve option to drill can be deferred over many years thereby extending the option.

Summary

Utilization of modified option theory is not in the conventional vocabulary among many oil patch dealmakers, but the concept is clearly implicitly considered as evidenced in many market transactions. This application of option modeling becomes most relevant near the bottom of historic cycles for a commodity. Here the DCF many times will yield little or no value even though transactions are being made for substantial values, thereby validating our belief that option theory is being utilized in the marketplace either directly or indirectly. If the right to drill can be postponed an extended period of time, i.e. five to 10 years, the time value of these out of money drilling opportunities can have significant worth in the marketplace.

However, we caution that there are limitations in the model's effectiveness. Black Sholes' inputs do not always capture some of the inherent risks that must be considered in proper valuation efforts. Specific and careful applications of assumptions are musts. Nonetheless, it can be a valuable tool if wielded with knowledge, skill, and good information. It provides an additional lens to peer into a sometimes murky marketplace.

About the authors

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com