Inter-asset dependencies can drive A&D activity in mature provinces

Bart J. A. Willigers and Zaur Muslumov, Palantir, Aberdeen, Scotland

Most of the oil and gas production in mature hydrocarbon provinces such as the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS) and the shallow water Gulf of Mexico (SW GOM) is exported via systems of offshore hubs, subsea pipelines, and onshore terminals. In many cases, infrastructure assets are owned by parties that are different from those who produce hydrocarbons.

Commercial agreements on transportation, processing, and operating services create economic dependencies between infrastructure owners and hydrocarbon producers. These intra-cluster dependencies may lead to material risks and opportunities that can be realized by both existing asset owners, and by potential buyers. Informed decision making, therefore, requires a thorough analysis of infrastructure assets and inter-asset dependencies, and an accurate modeling of associated commercial arrangements.

Rising transportation, processing costs in mature basins

The business landscape in SW GOM and UKCS has changed over the past decades, with many assets today nearing the end of their economic lives, and typically suffering from high operating costs and looming abandonment liabilities. This provides a strong incentive for owners to keep them operational for as long as possible or to divest them.

Although the importance of availability of reliable infrastructure in these conditions is widely acknowledged by industry participants, many still underestimate the costs, risks, and also potential business opportunities associated with the joint use of infrastructure assets.

During the development stages in the past in both SW GOM and UKCS, substantial investments were made in infrastructure networks. At that time, little ullage existed in transportation and processing systems and unit operating costs were relatively low.

The present situation is very different. Large parts of the existing infrastructure require significant maintenance investment as installations have passed their designed lifespan or will do so in the near future.

The gradual production decline implies that the transportation and processing infrastructure does not operate at full capacity. Both factors translate into much higher unit operating costs. As a result, understanding the economic implications of transportation and processing costs in mature provinces has never been as important as in the present, final, stage of production.

Tariff and cost-sharing arrangements

Most infrastructure assets receive either a tariff or a cost-share payment from their users. There is a key difference between jurisdictions where oil and gas infrastructure tariffs are regulated, and those where tariff levels are negotiated.

In jurisdictions with no detailed prescribed tariff-setting mechanism, such as the UK, users are generally charged a negotiable unit tariff paid on periodic hydrocarbon throughput. Over time, the total tariff payment decreases as a consequence of the natural decline of production. Once the service provider is no longer able to cover its costs and to generate profit with tariff receipts, many commercial agreements default to cost sharing.

In the cost-sharing phase each user in a cluster pays an allocated portion of the infrastructure costs in proportion to its share of the total throughput. Infrastructure owners also charge the uplift (profit margin), as a percentage of allocated costs (typically between 10% and 20%).

In jurisdictions with regulated tariffs, such as the US, tariffs generally represent the cost of service (both the historical capital recovery and ongoing operating expenses) plus the regulated rate of return or a profit margin. The policy objective is to limit the price-setting power of infrastructure owners, which arises from the fact that most hydrocarbon infrastructure assets are natural monopolies. Under such arrangements, since costs are included in the tariff calculation, all users within a cluster are automatically allocated a share of infrastructure costs, or, in other words, enter the cost sharing phase from day one.

Users prefer tariffs to cost sharing because tariff payments tend to be more stable and predictable. Also, users have more control over tariff levels than over infrastructure costs. In addition, during the cost-sharing phase, the payment made by a user is dependent not only on infrastructure costs, but also on the economic performance of other users within the same cluster.

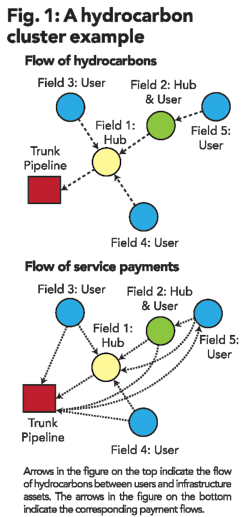

Further complexities arise from the fact that users often use various sections of the infrastructure chain, where each element may have a different ownership. As a consequence, user payments are subject to several commercial agreements that typically involve different terms (see Figure 1). In addition, some fields act as users of downstream infrastructure elements while serving as hubs for one or several upstream assets.

Dynamics of field cluster economics

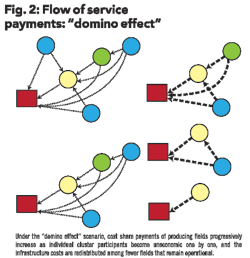

Once a user is in cost sharing, the operating costs depend on the performance of all other fields using the same infrastructure system. A particularly dramatic result of economic dependencies within a cluster of fields is the so-called "domino effect."

The "domino effect" as first described by Willigers et al. (2010) can occur when a user from the cluster ceases operation, which increases the cost burden for the users that remain on stream (see Figure 2). Such an increase in costs allocated to remaining fields is, therefore, likely to shorten their economic lives. This could in turn result in another user becoming uneconomic in the same period, triggering a chain reaction in which the growing costs for individual users might cause the entire field cluster to turn uneconomic.

While there are a number of available measures to mitigate against the "domino effect" impact, such as the removal of redundant infrastructure elements (e.g. unused processing trains and compressors) and more efficient maintenance, they are limited due to the lack of infrastructure scalability.

Because operating cost profiles of infrastructure assets are heavily dominated by fixed costs, it is very difficult to vary costs in line with current throughputs. As a result, the risks associated with the "domino effect" tend to be more pronounced in mature provinces with declining production.

A&D strategies and field cluster economics

Although uncertainties related to inter-asset economic dependencies clearly represent a risk to asset owners, they can also create valuable A&D opportunities for informed players. An important realization when evaluating and modeling field cluster economics is that a change in assumptions for one element of a cluster will cascade throughout the system of dependent fields, thereby impacting all connected parts of the cluster.

Players that have superior knowledge of the future potential or expected adverse developments in certain elements of a cluster can exploit such information asymmetry to their benefits. For example, development of a large new field and its subsequent connection to a hub could dramatically lower cost-share payments for the existing hub users. The reduction in the cost-share payments could significantly increase the value of these users, thus creating a material value gap between those players who are aware of the new development and those unaware of it.

In an alternative scenario, the infrastructure owners might have exclusive access to data that suggests that the decline in the total throughput of the infrastructure asset is accelerating faster than expected. As steeper decline rates imply higher unit costs, these players might exploit the information asymmetry by farming out their equity in users of the infrastructure.

Until now, firms that have focused on the acquisition of mature exploitation opportunities appear to have ignored the bigger picture. As transportation and processing costs have a large impact on the value of such opportunities, it is essential to understand the economic dynamics and inter-asset dependencies within infrastructure systems and field clusters. Players might, for example, be in a position to acquire infrastructure assets alongside equity in a user and create an opportunity to benefit from the economic upside resulting from further brownfield developments or exploration successes in the areas adjacent to their upstream assets.

Finally, it is important to note that the "domino effect" dynamics are broadly ignored in the assessment of economically recoverable reserves by the existing asset owners, which often makes reserves-based asset valuation methods inadequate in mature hydrocarbon basins.

Conclusion

Strategic and economic interdependencies between oil and gas fields and their offshore transportation and processing systems are complex. Events occurring in one part of the system affect all connected elements of the infrastructure network and their users, and can have a dramatic impact on asset values. Players who have better access to information, and who are able to accurately model the economic dynamics within infrastructure systems and field clusters will be in a position to identify A&D opportunities hidden from fellow players. OGFJ

About the authors

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com