An uneven playing field exists in oil vs gas pipeline development

Mark K. Lewis and D. Kirk Morgan II, Bracewell & Giuliani, Washington, DC

The dramatic growth of shale gas development in the United States over the last five years has led to countless new pipeline projects designed to move natural gas from unconventional production areas to market. Questions remain, however, as to whether the development of new natural gas pipelines will be matched by the development of pipelines to transport new oil production and the natural gas liquids (NGLs) that are a byproduct of the rush to develop shale gas reserves.

In the Marcellus, for example, Millennium Pipeline, Tennessee Gas Pipeline, Spectra Energy, Dominion Transmission, and Equitrans, among others, have all announced plans to construct new pipeline projects for purposes of transporting Marcellus natural gas production to northeastern markets. Although a lot of Marcellus production is rich in ethane – an NGL that is highly valued as a petrochemical feedstock – the development of pipelines to transport ethane to markets in Texas, Louisiana, and Ontario have not kept pace with the growth in production and the development of natural gas pipelines in the region.

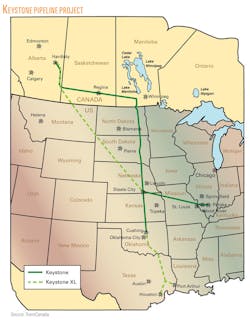

The same dynamic exists in the Bakken, where crude oil pipelines have been constrained and in allocation for years because pipeline capacity has not kept pace with growth in production.

Multiple factors contribute to the disparity between the pace of development between natural gas pipelines and oil pipelines, but chief among them is the difference between the way that the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) regulates natural gas pipelines pursuant to the Natural Gas Act (NGA) and oil pipelines and NGL pipelines (together referred to herein as "oil pipelines") pursuant to the Interstate Commerce Act (ICA).

The paradox is that the NGA's more heavy-handed and pervasive approach to regulation of interstate natural gas pipelines actually facilitates the development of natural gas pipelines. In contrast, the ICA's more light-handed approach to regulation of oil pipelines thwarts FERC's ability to facilitate pipeline development.

Interstate natural gas pipeline development

Pursuant to the NGA, a company may not construct, commence service on, or abandon an interstate natural gas pipeline without first obtaining FERC authorization. An entity wishing to construct or expand a new interstate natural gas pipeline is required to obtain a certificate of public convenience and necessity from FERC. The entity seeking the certificate files an application that includes the tariff that will govern service on the pipeline as well as the initial rates that will be assessed to the customers who will utilize the pipeline.

In an order on a certificate application, FERC decides not only whether the proposed pipeline project is in the public interest, but whether the proposed terms and conditions of service and rates are also in the public interest. Accordingly, prior to the commencement of construction, the project sponsor will know the terms pursuant to which it will provide service when the pipeline is operational and what rates that it will be able to assess.

Perhaps more important, FERC's issuance of a certificate comes with federal eminent domain authority as well as federal preemption of state and local laws that interfere with the FERC approved project. Thus, a FERC certificate provides a pipeline developer with the crucial authority to ensure that a landowner or state or local governmental body cannot block a project that has been found by FERC to be in the public convenience and necessity.

Interstate oil pipeline development

In contrast with the development of an interstate natural gas pipeline, FERC has no jurisdiction over the construction or abandonment of an oil pipeline. This is not a policy decision by FERC. Rather, it is dictated by the terms of the ICA, the statute that provides FERC with the authority to regulate the transportation of oil. The ICA provides FERC with the authority to regulate the rates and terms and conditions of service offered by an interstate oil pipeline, but the ICA does not provide FERC with the ability to regulate an oil pipeline's entry into or exit from the market.

There are significant project development hurdles associated with FERC's limited jurisdiction over oil pipelines. Foremost is the absence of FERC project authorization and the correlative absence of eminent domain authority and federal pre-emption of conflicting state and local laws.

As might be expected, each state has different rules and regulations governing the construction of pipelines. While one state may have a fast-paced application process in which a proposed project is subject to little scrutiny prior to construction, another state may have an entirely different process that imposes more burdensome requirements upon those seeking to construct a pipeline. Moreover, state or local permitting authorities may have anti-infrastructure agendas and there is no federal determination that an overriding public interest warrants that a project proceed.

Coordinating the different state approvals that are required for a single interstate oil pipeline can be a daunting prospect, especially with respect to environmental and landowner issues. In contrast with interstate natural gas pipelines, to the extent that an oil pipeline is unable to negotiate a right-of-way easement with a particular landowner, the oil pipeline may be able to seek eminent domain authority from the state in which the landowner resides. If this proves unsuccessful – or eminent domain authority is simply not available in that state – the pipeline may have to undertake a costly and time-consuming re-route to avoid the property of the disagreeable landowner. As a result, acquiring the rights-of-way easements for an interstate oil pipeline is more complicated and costly than for an interstate natural gas pipeline.

The absence of FERC authority over the entry of an oil pipeline into the market means that there is no requirement or even authority for FERC to authorize construction of an oil pipeline. Nor is there a requirement for FERC to approve an oil pipeline's rates or tariff prior to commencement of service.

A problem created by the lack of prior rate and tariff approval is that project sponsors lack certainty as to the revenue they will be able to generate once the oil pipeline is completed, as well as the service terms that the pipeline will be required to offer. Fortunately, starting in the mid-1990s, pipelines began to request and FERC began to issue declaratory orders for purposes of providing project sponsors with a level of certainty as to rates and service terms for yet to be constructed oil pipelines.

In essence, the developer of a prospective oil pipeline may file a petition asking FERC to issue an advance ruling as to the rates and terms of conditions of service that the pipeline will be able to utilize. Obtaining a declaratory order prior to construction is not a requirement and is not utilized by all prospective oil pipelines. Still, the declaratory order process can serve as a useful tool to alleviate some of the regulatory uncertainty that might otherwise deter investment in a proposed oil pipeline project.

Even so, as evidenced by the rate complaints filed against the Enbridge Southern Lights project notwithstanding the prior issuance of a declaratory order, a degree of regulatory certainty continues to exist until "live" rates tariffs are filed by the pipeline when service commences.

The way in which capacity is allocated on an oil pipeline also creates development obstacles. Pursuant to the ICA, oil pipelines are regulated as common carriers, which means that oil pipelines must provide transportation service to any party that reasonably requests service. This means that if an oil pipeline is constrained and a new customer asks for transportation service, the oil pipeline's capacity must be allocated among its customers – including the new customer – and the existing customers all lose some of the capacity they otherwise would have had.

In contrast, on an interstate natural gas pipeline, service is provided to customers on a contract carriage basis that entitles customers to firm capacity on the pipeline. If a new customer requests service on a constrained interstate natural gas pipeline, the pipeline would not be required to provide service to the new customer. If a natural gas pipeline is fully contracted, a new shipper is out of luck.

The relative inability, subject to certain exceptions discussed below, of an oil pipeline to offer firm service can deter customer-backed pipeline projects. Simply put, prospective customers are less likely to backstop a new pipeline by providing a revenue stream through a long-term contract if they incur a fixed financial obligation without an assurance that they will have firm rights to the pipeline's capacity or, worse yet, that their right to capacity will be no different than that of any other customer – including customers who have not committed to the development of the pipeline.

FERC does allow a prospective oil pipeline to offer discounted rates to shippers that commit to long-term contracts. In addition to having the benefit of lower rates, the customers who sign long-term contracts can have a higher priority in an allocation situation, but they nevertheless remain subject to allocation.

Less common, a pipeline may set aside capacity free from any prorationing for shippers who agree to pay a premium rate. Thus, the shipper backstopping the project has to pay a higher rate than the shippers who just show up after the fact without a long-term commitment, in contrast to natural gas pipelines where the anchor shippers typically pay lower rates.

No easy answers

Looking at the need for new oil pipeline development and the regulatory hurdles that stand in the way of such development, it is tempting to argue that FERC should regulate oil pipelines like natural gas pipelines. However, providing FERC with the authority to grant federal rights of eminent domain and preempt state and local laws for oil pipeline projects would require major changes to the ICA.

The same is true if FERC were to regulate oil pipelines as contract carriers rather than common carriers, i.e., if FERC were to regulate oil pipelines the same way that FERC regulates natural gas pipelines. It is unlikely that FERC, as a matter of policy, could permit contract carriage akin to that provided by natural gas pipelines and still remain true to the ICA.

Fundamental changes to the way in which oil pipelines are regulated would require Congress to amend the ICA – a scenario that seems unlikely in the current political environment. Even if there was the political will to amend the ICA, regulating oil pipelines as contract carriers could be a mixed blessing. While it may facilitate the development of much needed oil pipeline development, it would also subject existing and new oil pipelines to a much heavier handed form of regulation.

Rather than a statutory overhaul, the most effective way to facilitate the development of new oil pipelines is for developers to think creatively about ways to work within the confines of the ICA to attract investment. The use of declaratory orders to obtain regulatory certainty for creative rate, contract and capacity allocation solutions may be the best way to try to push the boundaries of what FERC will do within the confines of the ICA. The industry should continue to work with FERC to implement policies that are consistent with the ICA and at the same time facilitate much needed investment in new oil pipelines.

About the authors

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com