The effect of oil price cycles on investors

NADIA MARTIN WIGGEN, RYSTAD ENERGY

DURING THE SUMMER MONTHS, what is normally peak seasonal demand for oil in the US, we see the oil market struggling to break out to higher prices, instead maintaining a trading range lower than the 2017 peak. While activity levels by North American shale producers have risen since the start of 2017, we see share prices for oil companies have retreated from Q1 2017 highs. Since May 2017, we again see share prices in the oilfield service sector have collapsed faster than the index of exploration and production (E&P) companies like we saw in 2008 (see Figure 1).

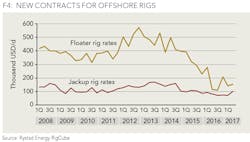

While the mood among oil companies has been less positive since oil prices started retreating during the second half of 2014, we have observed significant decreases in breakeven oil prices both in shale and offshore. Rig rates fell significantly since Q2 2014 through Q3 2016, contributing to lower costs for E&P companies and removing the value proposition of holding OFS company stocks for investors, compared to steadier E&P stock prices.

While many companies continued to drill at the start of the price downturn, the increase in delayed completions was the first sign of waning times. Thereafter, rig counts fell, especially as oil prices fell beneath US$40/bbl. Oil prices bottomed during Q1 2016, and the oil industry started to recover organically.

Nevertheless, OPEC grew impatient with the oil cycle after the 2016 summer and began proposing a production cut amongst members of the cartel and additional producers, driving enthusiasm for a faster recovery in the oil market and attracting investors.

Despite the downturn in the oil sector, shale companies have not experienced real pressure, as they have continued to receive funding throughout this price cycle, notably through the end of 2016. Shale companies with significant DUC inventories increased completions during Q4 2016, as the OPEC and non-OPEC production cut was confirmed. The deal changed the previously morose sentiment amongst shale producers to a positive one, as 2017 business plans and budgets called for significant increases in activity.

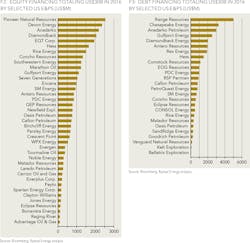

Rystad Energy estimates that shale companies raised an additional US$100 billion in 2016, including US$30 billion in public equity (see Figure 2), US$30 billion in public debt (see Figure 3) and US$40 billion in private equity. Most of this new capital has been used to repay debt and to acquire new acreage. We see the US shale industry in much different shape now versus two years ago when distressed balance sheets weighed on the activity of all but the top performers.

As a result, we now consider the US drilling industry well prepared for another long-lasting investment cycle, with CAPEX likely exceeding cash flows for several years, as we saw in the previous upcycle. In this new upcycle, the first limiting factor will be service price inflation as we have already seen in Q1 2017. This will be followed by infrastructure limitations, especially in the Permian, where we could again see widening basis spreads by early 2018.

Utilizing the additional capital raised through 2016, shale companies have significantly increased both drilling and completions since the start of 2017. Nevertheless, shale completion rates have lagged the increase in drilling. While we have observed higher completion rates for Q2 2017, they are not commensurate to the drilling rates, leading to growing inventories of DUCs. For the oilfield service (OFS) sector, increased activity by shale producers has led to an increase in revenues, and enthusiasm amongst investors that we had seen the bottom of the oil price cycle and that it was time to invest in OFS companies. However, as revenues picked up, initial costs to OFS companies rose, driven by the lack of maintained equipment during the downturn and the need to hire new staff to fulfill demand for services. As OFS companies reached capacity for hydraulic fracking, pressure pumping, and sand supply in Q2 2017, investors punished the oilfield service sector.

In conclusion, OPEC's decision to intervene in the oil markets by cutting production from Q1 2017 through Q1 2018 created an event-driven expectation amongst investors in the oil market that has failed to materialize in an inventories-drawing market. Shale companies benefited first, as short oil cycle producers, though their share prices have also suffered as oil prices have failed to meet investor expectations following the OPEC agreements. OFS companies received an increase in investments earlier in 2017, but this proved initially short-lived despite new offshore rig rates up steeply since Q3 2016 (see Figure 4) and our forecast of even steeper growth in onshore rig counts. We see the jack-ups market showing a small recovery already this year (2017), and expect the floaters market to start showing recovery next year (2018), driving the recovery in the OFS sector amongst investors.

For E&P companies and oil prices, investors will benefit most when the long oil cycle again starts to dominate, most likely from the first half of 2020. Shale production growth will have been maintained, but the non-OPEC, non-shale output will be missing in the oil markets significantly. First, the lack of infill drilling in mature fields will have limited output by one million barrels per day in the current short cycle, and second, the lack of new field sanctioning since 2015 will have cut output significantly five years forward.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nadia Martin Wiggen is vice president of the markets team at Rystad Energy and co-author of the monthly Global Oil Market Trends Report. She has 10 years of experience in commodity markets analysis (spanning oil liquids, gas, power, coal, renewables, agriculture, metals and freight) and trading from Morgan Stanley and Phibro. She holds an MSc degree from the Stockholm School of Economics and a BSc from Georgetown University's School of Foreign Service.