The debate over future oil prices

Why forecasters almost always get it wrong and why nobody listens when they get it right

CHARLES CHERINGTON, ARGUS ENERGY MANAGERS, HOUSTON

NOTHING IS MORE AMUSING than watching oil industry forecasters, the legions of pilot fish attached to the great industry whale. The number of these fish dedicated solely to predicting the whale's future direction is in the high thousands. Market forecasters work at contract research firms, investment and commercial banks, hedge funds, oil midstream and downstream enterprises, power companies, airlines, energy private equity firms, and government agencies, just to name a few.

All forecasters share a common trait: they are wrong. Some are only wrong most of the time and most are wrong all the time. While other industry whales also support vast populations of wrong-headed pilot fish (stock market, anyone?), nothing compares to the oil and gas sector. One day, an enterprising PhD student will collect all the past forecasts of the wise and the worthy and carefully document their spectacular legacy of wrongness. Even then, the forecasting ecosystem will continue to thrive, undaunted.

Why is the market so unknowable, and why do we keep trying nonetheless?

The forecasters persist in casting bones, reading tea leaves, and firing up their hard drives because they are paid good money. Forecast consumers are inherently gullible. It is a strange world in which willing consumers consume products defined principally by their persistent wrongness.

But what question is it that forecasters try to answer? If you took the weight of all the papers written about the short-term market-what will happen in the next year or two-you would fill several large dumpsters. Work devoted to the long-term market? Perhaps a single trash can. Yet, the short-term market's noise generally overwhelms its faint signal, whereas the long-term market actually reverses that equation at certain points in the cycle. However, forecasters give the people what they want, which tends to focus on tomorrow or next month. After all, what happens tomorrow drives most trading and stock prices. Ask today's oilfield service company CEO about prices in five years, and he'll have to restrain himself from socking you. His chief preoccupation is making payroll next week.

There's another reason people keep buying what the soothsayers sell. Occasionally, they are right. Once in a while, clear signals emerge from the noise, and when they do, they can be extremely valuable. But in a world of overwhelming noise, how do you know when you are hearing a signal? In 2014, oil inventory was bloated and getting worse. Daily supply was greater than demand, with no end in sight. But few market players seemed to hear the signal, even though it was deafening. That's because when the soothsayers are wrong so much of the time, when they start yelling about a pack of wolves at the village gate, very few people listen. It is also because the market was convinced that the long upcycle would continue, as if by magic. Even when OPEC elected not to cut production in late 2014, market sages ignored the deafening signal and blithely declared that the downturn would be short-lived.

SHORT-TERM VERSUS LONG-TERM MARKETS

Short-term markets have, in recent years, gone from merely unpredictable to completely crazy. Several factors have contributed:

The volume of oil derivatives has grown to 15x the quantity of the physical commodity being produced. Derivatives are either ignored or misunderstood by much of the market. Even for those who try to include derivatives in their analysis of near-term behavior have to contend with market opacity. Imagine trying to predict the driving performance of a Mini Cooper on a highway. Unbeknownst to you, it is attached by a short chain to 15 invisible Harley soft tails also moving down the highway. Good luck.

Short-run oil pricing behavior is heavily influenced by players reacting to single factors like an OPEC announcement. Two distortions tend to arise: first those factors don't tend to be clearly understood, and second, they tend to be over weighted. How much ink has been spilled in the last two years, both in exuberance and despair, in response to OPEC announcements? A great deal.

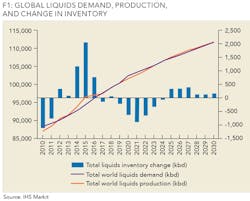

Shale. In one sense, shale isn't a big deal. Five million barrels of daily supply in a 97 million barrel market isn't much. However, the global oil market can be thought of as an ecosystem. The river of supply (Supply River) enters the North end of a lake of inventory (Lake Inventory) and exits the south end through a river of demand (Demand River). When Supply River pours more into Lake Inventory than Demand River drains on the other end, the Lake grows. In 2012-2013, the lake held about 4.8-4.9 billion barrels, or 50 days of supply. By the first quarter of 2015, it had grown to 5.4 billion barrels. Why did an additional four days of supply eventually cause the market to crash and launch one of the longest, most severe downturns in history? Shale turned the industry-and the world-upside down.

Imagine that someone waves a magic wand and adds a five-million-barrel-per-day tributary to Supply River (Shale Tributary). That's shale. It threw the whole global system out of balance. Without shale, Lake Inventory would be running dry, and prices would be over $100 per barrel. With shale, the market is oversupplied, the Lake is overflowing its banks, and even with OPEC cuts, it will take a few years for a reduction in the Supply River to offset the impact of shale and allow the Lake to start draining. The problem is that the Shale Tributary does not behave like the Supply River. Supply River flows change slowly, over a span of years. E&P capex spending today leads to increased production in five or ten years. Or at least it did until shale came along.

Shale responds in months to small, transient price signals. These days, shale producers can hedge whenever oil prices get into the fifties. So, take one dose of market overreaction to a single piece of news, fortify it with derivatives, and prices suddenly move inexplicably. Then shale producers immediately lock in hedges, which crystallizes an irrational short-term price increase with a meaningful dose of new supply. Presto - markets are now meaningfully distorted in the short run, and all because a few market players got excited about a vague signal from OPEC's headquarters in Vienna.

Shale has made the US the new Saudi Arabia. We are now the swing supplier to the global oil ecosystem (see Figure 1).

Shale keeps getting better. Today, shale wells produce twice as much for less cost than yesterday. Nobody knows what tomorrow will look like, but it will be better again. It is a reasonable bet that the lion's share of productivity gains are behind us-but not a certain one. Shale gains mean that predictions about US output have to factor in unknowable future well results. Shooting at a moving target with a blindfold poses challenges.

But wait, there's more: capital markets are crazy. After the 2007-2008 recession, central banks around the world turned on the monetary spigots. Banks can borrow at almost no cost. The problem is, in a low-growth global economy, they can't lend. Then they found the oil industry. Both debt and equity capital have been freely available to the shale industry, with a brief timeout during the current downturn. Loose capital markets have provided the perfect storm. Bear in mind that in simple terms, shale producers are cash flow neutral at $50 oil, even with hedges. More capital anyone?

For all these reasons, predicting what's going to happen in the near term is simply impossible. Did we mention that Venezuela is collapsing, Libya could add or lose a million barrels a day, depending on the mood of the local militia commander? Saudi rig count is high, even as they restrict supply; OPEC's ability to enforce compliance has typically been limited, and so on.

But the biggest uncertainty comes from shale, with well productivity on the rise, capital markets at the ready, and hedges locking in new drilling whenever short-term market sentiment bids up prices for a few days. Add a giant, opaque derivatives market and one can being to appreciate that market forecasters have to peer through a major to track the movements of a lizard a mile away.

LONG-TERM FORECASTS

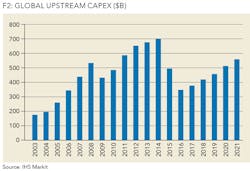

In the long-term, forecasters track Supply River feeding Lake Inventory from the North and Demand River emptying the lake from the South. While the Shale Tributary has wrought complete havoc on the short-term market, it simply can't contribute enough to the oversupply picture in the long run to prevent the older, slower moving oil ecosystem from reasserting itself. Supply River is fed by global upstream spending. Over the past few years, spending has declined sharply (see Figure 2).

A simple truth exists in the global oil industry: global exploration and product capex drives future production. However, as we observed earlier, a lag effect exists. Exploration spending outside of US shale drives production five to ten years from now. Today, meaningful new supply is coming on line from projects started years ago in the North Sea, Brazil, Kazakhstan, and the Canadian oil sands.

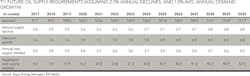

So what about tomorrow's supply? Supply River has a big job in the long run: it has to replace global declines of roughly 2.5% per year, and it has to compensate for the growing effect of Demand River, whose flow, as a rule, increases steadily every year. It surprises most industry observers to learn that global liquids demand has grown every year for the last 30 with the exception of 2008-2009.

Some simple math tells us that Demand River grows predictably and steadily in the long run, and that Supply River simply won't be able to keep up, no matter what the Shale Tributary might do (see Table 1).

Why can't supply keep up when we get into the 2020s? As low prices choked global capital expenditures, new discoveries in 2015 and 2016 reached lows not seen since the 1940s, when spending was first tracked. In short, we are at a point today when the noise from short-term markets is overwhelming, but the signal from long-term markets is loud and clear.

Some general conclusions can be drawn from that signal. For most investors, that signal doesn't have much value. For public company CEOs, what matters most is the next ninety days. For hedge funds targeting oil, the near term has enormous importance. After all, a few bad quarters, and redemptions can put a hedge fund chieftain out of business.

However, long-term trends matter deeply to a subset of the investment world. Right now, the 2020s are telling a very interesting story. That's because by the time the wider world realizes that we are facing a major supply shortfall in the 2020s, the Shale Tributary will not be up to the task of balancing the market. It won't even be close. Rebalancing markets will be the job of the Supply River. But as we've seen, Supply River volumes take years to increase. Start spending on a new deepwater project today, and first oil might be well over a decade in the offing.

We know a few things today: first, new discoveries are at historic lows. That does not augur well for future supply. Second, when prices rise in an effort to fill Supply River, it will take years for those prices to translate into higher volumes. Supply River is famous for responding to price signals. A sharp increase in prices triggers an upsurge in activity, today. But that activity doesn't deliver increased volume for many years.

In the short run, the Shale Tributary has changed everything. But as we look into the 2020s, we see supply shortfalls that can only be filled by a dramatic increase in capex. Today's oil prices don't support that capex. Shale has saved us from high oil prices today, but ensures them tomorrow. Long-term investors who take note will certainly profit from this information, but only if they can separate the signal from the noise.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Charles Cherington is co-founder and chairman of Argus Energy Managers. AEM is a Houston-based privately held company with equity interests in distinguished boutique investment managers focused on the energy space. This affiliate network of private equity firms currently manages, in aggregate, more than $1.7 billion of committed capital, focused on upstream, energy services and equipment, and fixed-income investments.