Horizontal drilling boosts production in Mississippi Lime

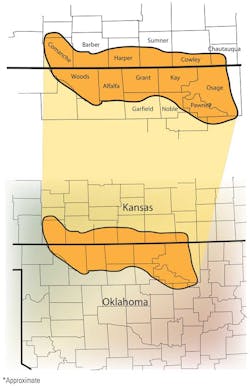

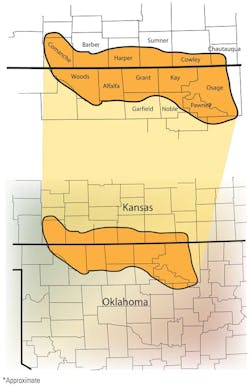

Technology typically used for drilling and completing wells in shale formations has created a resurgence of interest in a non-shale play, the Mississippi Lime in northern Oklahoma and southern Kansas. Operators have been sinking the drillbit into the Mississippian play for decades, but the vertical wells produced less-than-exciting results. Thousands of wells have seen only hit-and-miss success.

Today, however, using a combination of horizontal drilling and multi-stage hydraulic fracturing, they are bringing in wells with hundreds of barrels of oil equivalent in production per day and ultimate per-well recovery estimated at up to 400,000 barrels. And those wells can cost less than $2.5 million each.

Previously, vertical wells into the Mississippi Lime formation might be lucky and get into the fractures. However, just as many wells were not so lucky. Geologists say the formation is made to order for horizontal drilling.

Wells in the Mississippian play frequently produce a lot of water, which is something operators don't mind because generally the more water and fluids you see, the more oil you're producing, said an operator active in the play.

The Mississippi "Chat" is located atop the Mississippi Lime and is considered a very good hydrocarbon reservoir. Chat reservoirs are widespread and vary in thickness from a few feet to 80-feet thick. The Chat is comprised of chert, limestone, and dolomite with porosities varying from 3% to 35%. It has long been targeted for drilling with traditional, vertical wells.

The Mississippi Lime underlies the Chat and this zone is also very productive for hydrocarbons. Geologists describe it as a "deep water to shallow marine limestone sequence with interbedded dolomite facies enhancing porosity and permeability." Porosities range from 5% to 15% with water saturations ranging from 25% to 60%. Net porosity thickness greater than 5% range from 10 to 100 feet, with an average of 30 to 50 feet.

The Mississippian rocks below the Chat are tighter and less porous (it is a carbonate formation rather than shale), therefore fracturing combined with horizontal drilling are needed to make the Mississippi Lime economic. Operators are currently targeting the more liquids-rich parts of the play due to chronically low natural gas prices compared to crude oil and natural gas liquids.

Among the companies operating in the Mississippi Lime are: Chesapeake Energy, SandRidge Energy, Devon Energy, Apache Corp., ExxonMobil, Range Resources, PetroQuest Energy, Eagle Energy, Pablo Energy, AusTex Oil Ltd., Magnolia Petroleum, and Petrodyne Petroleum – to name a few.

The gas-rich shale plays first brought major producers back to domestic fields about 10 years ago. Names like Barnett, Marcellus, Haynesville, Bakken, and Cana Woodford became synonymous with unconventional drilling and revived US energy reserves.

With chronically low natural gas prices, the move now is toward deposits containing mostly oil and natural gas liquids. The Mississippi Lime's ratio is often 52% to 55% oil, according to reports.

The Lime is a reasonably low-cost play where hydrocarbons have been found before, with a lot of wells drilled in the past. And that gives you good data points.

In fact, the Mississippi Lime, which begins at a depth of about 5,000 feet on average, has about 17,000 vertical data points – seismic information, etc. – throughout the trend. The growing number of horizontal data points now exceeds 500.

The nice thing about this trend versus shale is that it requires low-horsepower equipment, and smaller players can be competitive.

The limestone's porosity and natural fractures also can mean less expense on the drilling and hydraulic fracturing parts of the project. Expenses can total half and even a fourth of typical unconventional well efforts.

As with the Bakken and other shale plays, there are "sweet spots" that will see great production and there are other wellsites where profitability is questionable. The key is acquiring acreage in the right locations, which can be an art as much as a science.