CHINA: An Unconventional Direction

Cover photo: "Acrobat show, Chaoyang Theater" by Andrey Muntyan

This sponsored supplement was produced by Focus Reports. Project Directors: Federica Torgneur and Andrey Muntyan. Project Coordinator: Chiraz Bensemmane. Project Assistants: Nala Nouraoui and Karina Mereuta. Project publishers: Crystelle Coury and Ines Nandin. For exclusive interviews and more info, please log onto www.focusreports.net or write to [email protected] |

In March of this year, China's Ministry of Land and Resources announced that China likely has the largest reserves of shale gas in the world, estimated at 886 trillion cubic feet (TCF). The authorities had by then already trumpeted their ambitions of commercializing shale by 2015. Ultimately, says Jiao Xu Ding, founder of the landmark Chinese oilfield service company Copower, these vast resources may be able to support China's current population for the next three centuries.

An Unconventional Direction

The announcement comes on the heels of a turning point for the country's oil and gas industry. In the exploration, production, and marketing of traditional oil and gas, business has long been channeled through China's principal 'Big Three' National Oil Companies (NOCs): China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), and China Petrochemical Corporation (Sinopec). Generally, non-state upstream enterprises can participate in E&P plays only through a production-sharing contract with one of the three. Service providers, meanwhile, must contend with extensive state-owned competition: each NOC is an umbrella organization housing every imaginable subsidiary from equipment manufacturer to engineering company to research institute, and the state gives preference to its own.

BP's flagship investment in China - the SECCO petrochemical complex

The government, however, has introduced a surprising directive: by the second round of bidding, shale blocks will be tendered not only to national players, but private domestic firms as well. CNOOC's chief energy economist, Chen Wei Dong, speaks about the power of open competition in North America in inciting industry. In China, too, the private oil and gas industry is starting to mushroom, and the opening of the shale sector is more broadly emblematic of the authorities' increasingly capitalistic mood.

Opportunity is also drawing the international industry to China in droves. China first introduced the 'Reform and Opening Up' policies in 1984. Under this series of legislation, the state formally opened its doors to foreign players, and the market has never looked back. The National Energy Administration's deputy director of Oil and Gas, Hu Weiping, readily acknowledges the value that international businesses bring to the China market, crediting the open-door policy for helping China to rapidly modernize.

Hu Weiping, deputy director general of oil and gas division, National Energy Administration of China

"During the last three decades of Reform & Opening Up," Hu says, "the Chinese oil & gas industry has been able to to learn much from advanced international companies. Our industry has improved in terms of technology, finance, management, and—most importantly—ideas."

Internationalization in China is both internal and external. As it has let companies in, it has directed its own 'Big Three' to 'Go Out.' Over the last years, each company became partially stock-listed, achieved increased autonomy from the state, diversified its activities, updated its technologies, skilled up its managers, and joined the Forbes Global 2000 list (at #7, #24, and #146, respectively). According to Ernst & Young, in 2009, 2010, and 2011, China's NOCs accounted for 12-15% of all global M&A spend in the oil and gas industry. Chinese companies are now major players in traditional IOC areas such as U.S. shale gas, the Canadian oil sands, and Brazilian deepwater.

Private Chinese industry followed the NOCs abroad, but quickly found a market of its own; many private companies, in fact, went global even faster than their state-owned counterparts.

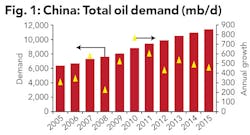

China's oil companies sought the international market because, until unconventionals came onto the scene as a dark horse, the domestic market had grown too small. China has been steadily watching its energy basins deplete. Its top four oil fields—including its largest, Daqing basin in the northeast—have gone into decline. A net exporter until 1993, Chen notes that China today consumes 9 million barrels of oil per day and produces 5—an import imbalance of 125%. Natural gas became a net import in 2007; coal in 2009. Meanwhile, the International Energy Agency projects that over the next 25 years, China will alone account for more than 30% of growth in global energy demand.

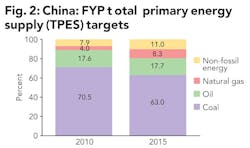

Just as it seeks greater energy autonomy, China seeks to lessen its carbon footprint. A vast industrial economy, the country's pollution clouds are visible from space. In natural gas, the authorities have found a green, and ostensibly abundant, fuel, and plan to double its share in the energy matrix to 8.3% by 2015.

The Rebalancing

The developments of the last years—the promotion of green growth, the internal and external globalization of the industry, the precipitous emergence of the private sector, unconventional gas the poster fuel of the future—are all wound in a greater vision. They are consistent with the 12th 5-Year Plan, China's latest strategy for national socioeconomic development, effective from 2011-2015. At the end of this year, China will quietly experience a leadership shift that occurs once every decade. Current prime minister Wen Jiabao, and current president Hu Jintao, leave to their successors a progressive agenda.

Raphael Schoentgen, chief representative of GDF Suez's China operations, opens his interview with Focus Reports with the following admonition: "The first idea we come across is a very, very strong one: that China cannot proceed with its existing path of development. It cannot follow the same energy pattern, and must shift completely—toward cleaner energies, and more energy efficiency." Schoentgen calls the nation's 12th 5-Year Plan a "rebalancing."

Raphael Schoentgen, chief representative, GDF Suez China

The National Energy Administration's Hu Weiping speaks of a dual-pronged approach: "To solve the problem of increased energy consumption, we need to ensure supply while controlling demand as much as we reasonably can. We need to adjust the structure of our economy and change the pattern of economic growth. In a recent address to the National People's Congress, prime minister Wen Jiabao gave an overview of current government initiatives. The expected GDP growth rate for 2012 is set at 7.5%, which demonstrates our resolution to slow down our growth and adjust our structure."

More Than Merely Interesting

To be sure, as China moves to double the share of gas in its energy mix by 2015, the country will at first rely heavily on imports: LNG shipped from neighbors such as Australia and Qatar (17 million tons of LNG will be imported to China in 2012, according to a study by WoodMcKenzie); or pipeline gas directed via the 1,118-mile natural gas pipeline coming from Turkmenistan, China's greatest single source of gas today.

However, to realize targets of improved self-sufficiency, China is putting greater stock into its own unfarmed backyard. Offshore gas plays in Bohai Bay and the South China Sea—both in shallow water and, today, deepwater—are generating increased attention, and the government is investing US$40 billion in the sector over the course of the 12th 5-Year Plan to support exploration and the development of infrastructure.

Ole C. Willumsen, president, Statoil China

But where the country is truly betting big is unconventionals. In addition to the abundance of shale, the Ministry of Land and Resources currently estimates that China's coalbed methane (CBM) deposits may be the third largest in the world by volume, at approximately 120.7 TCF.

When Ole C. Willumsen, country manager of Statoil in China, arrived in the country in August of 2010, he found a distinct dynamism in the market. Willumsen tells Focus Reports, "It is difficult to pinpoint the moment when the exploration and production of unconventional fuel transitioned from something that was merely 'interesting,' to something that everyone is absolutely eager to take part in. I have the feeling that the drive warmed up around two years ago. I think the next couple of years will be crucial in terms of deciding on the potential commerciality in the various basins. Hopefully, China's resource base will not disappoint."

An overnight success?

Baker Hughes' Mike Dolman on the prospects of shale gas in China

Many experts are skeptical about China's shale gas potential, saying that, while it does appear that reserves are vast, it is too early to tell how economically viable, or geographically challenging, exploitation will be. What is your opinion? Can China shale be the next success story for this industry, and for Baker Hughes?

This is one of the big questions in our industry today—will China be the next place for shale gas, and for unconventionals?

The potential resources are there. Personally, I believe that the growth opportunities could be huge for both operators and service companies. However, from what I have seen in my three years in China, the Chinese take a very long-term approach. By thinking in broader terms, a strategy is being implemented to move from coal to cleaner energies. I see the investments being made. And yet, it will take time.

Mike Dolman, vice president north asia, Baker Hughes

We will have to contend with challenges. The business here is completely different from North America. For instance, even the fundamental logistics are challenging—many of the areas that appear to have resource potential are in difficult-to-access, mountainous terrain with high population density. There is a potential lack of water sources for hydraulic fracturing. China must invest, too, in its pipeline network, as the gas must ultimately be transported to consumers.

For these reasons, I believe that a 'shale gas boom' will not happen overnight. However, I see a very bright future, because political will is clearly behind the exploitation of this resource. Baker Hughes is investing in these opportunities because we believe the market will develop.

Xu Chengzhu, president, Schlumberger China

Unconventionals were, of course, a transformational resource for North America, which continues to aggressively mine its reservoirs on its way to greater and greater energy autonomy. China has made it no secret that it would like to do the same. Cheng Xu, president of Schlumberger China, believes that it can: "I believe that China will be able to replicate this story. The reserves are there. The geology is different, and more difficult—but the Chinese will find a way. Indeed, they must find a way, because they need these resources."

China CBM: A history lesson

Far East Energy (FEE) is a micro-cap upstream CBM company with American roots and an operation based in China. It has three blocks in the region, and one of these—situated in Shaoyang County, Shaanxi Province—has yielded a large area of high-permeability coal that FEE's country manager Robert Hockert believes "represents a turning point in the development of China's CBM industry."

Mr. Hockert, historically, some major energy companies—including Chevron and BP—exited China's CBM sector in the early 2000s, citing policy constraints and low demand in the domestic market. Why did a small Houston-based enterprise decide to tackle what many would view as a challenging market?

Bob Hockert, China country manager, Far East Energy

Most major CBM assets that are developed today are discovered by small independent companies—the fact that the majors pulled out does not necessarily speak negatively about the potential of the resource. Having said that, at the time, gas demand was a shadow of the enormous demand that exists today, and then there were no pipelines and poor pricing. Today, demand is off the charts; pricing is very high compared, for instance, to U.S. gas prices; and pipeline access is increasing although still challenging. Those same majors are now looking at China CBM again.

Since 2005, when we first started really drilling, we have made a major discovery, and we have applied for reserve qualifications. We are pretty excited—we believe we have a great asset!

And yet, the fact that China's geology is quite unlike North America's is not lost on the industry. Expectations are positive, but in many cases reserved, as the gas sits trapped in difficult terrain in inland provinces like Shanxi and Sichuan.

Chen Liming, president, BP China

The unconventionals story in China has so far been fraught with delays. CBM, for instance, has been under development for 10-15 years, and yet results have been thin: BP's China president Chen Liming points out that "the country's CBM production is still very small; it currently produces only 1.5 billion cubic meters of the gas a year. We must look at what has happened in the CBM industry, and ask ourselves what we can do differently in shale gas."

China has in fact taken steps in the right direction for both commodities. According to Chen, poor handling at the state level obstructed the CBM sector; today, a wave of new legislation has cemented CBM exploitation as a national priority and an attractive commercial undertaking. For shale, the intentions of the government are perhaps doubly clear.

Pipeline infrastructure and other midstream foundations, too, are nascent but under hurried development. Halliburton country VP Desmond Kong notes an advantage of the top-down system in China: "Everything is feasible if the government decides that it will sponsor or support it. The historical response of the government is well known: that infrastructure will be built—and it will be built in good time to support their targets."

When China opens a Window…

Shell's in-country chairman Lim Haw Kuang always tells his staff: "Let us not focus first on what we want. Let us focus first on what China needs in terms of energy, and how we can address those needs."

China's needs are growing. As the world's largest energy consumer, China represents a pivotal downstream market. Companies like Shell and BP actively participate in niches like lubricants, petrochemicals, and petrol marketing. Gas giants like GDF Suez are signing long-term deals for the provision of LNG to Chinese partners. An erstwhile compact, and notoriously closed, upstream market is looking increasingly attractive as well: private multinationals and national companies like Statoil alike are looking to partner with local organizations on natural gas plays—a situation prognostic of much-increased foreign presence in the sector.

Lim Haw Kuang, executive chairman, Shell Companies in China

Lim remains largely mum about the issue, but Shell's extensive exploration partnership with CNPC has yielded what appears to be a large volume of recoverable shale gas in Sichuan, and others are eager to follow suit. As a measure of what is possible for foreign companies with the right value proposition, Shell China has grown from 4,000 people to 18,000 people in only the last 4 years.

Service needs in this environment are meanwhile changing. To Yann Reynaud, head of Schneider Electric's Infrastructure Business in China, this has meant evolving his approach. Reynaud notes that, whereas some years ago, the Chinese sought "discreet services," today they want multinationals to act as full partners, taking responsibility for their portions of a project and providing solutions rather than products.

Yann Reynaud, vice-president, head of infrastructure business, Schneider Electric China

Reynaud speaks, too, of being in China, for China: "Whatever you do, your competitors will come to this market and develop products here—whether these competitors are international or local. It is very naïve to think that just because you are not present in this manner, the Chinese customer will not gain access to the technology they want. If they do not get it from you, they will get it from someone else.

"We look at the concept of windows of opportunity. China often opens windows; what, sometimes, a European company does not catch, is the fact that these windows are not open for very long. You catch the window, and you capitalize, or you run after the train. And the train runs very fast, so usually if you are running behind it, you are already too late!"

Shifting Stomping Grounds

Andy Benson, managing director China for Core Laboratories—a specialized U.S. oilfield services company that works to optimize reservoir return—founded his subsidiary in 2005. Core Lab works with both domestic players and IOCs, but has found that it is easier to offer their premium-priced services to their traditional, multinational clients.

Benson says, "We are beginning to really focus on the IOCs working in China. They are already familiar with Core Lab's reputation for quality, and they are beginning to partner with the domestic Chinese oil companies to explore onshore. Many of these partnerships are for unconventional gas reservoirs, and Core Labs has more unconventional reservoir data than just about anyone.

Andy Benson, managing director, Core Laboratories China

"The IOCs first entered the Chinese petroleum market via the South China Sea. Next they moved into the Bohai Bay area. Now everyone is interested in the unconventional gas reservoirs in Sichuan. These new reservoirs are challenging—deep, with low permeability and porosity. We have seen huge strides made in the development of such reservoirs in the US, and now the IOCs want to bring this technology to China."

If an oil company or service provider can form strong relationships in the China market, moreover, the spillover effects may prove lucrative abroad as they capitalize on China's wave of internationalization. GDF Suez, for instance, has a substantive business within China, with 4 Suez Environment companies present in the region and the introduction of the Energy business in 2009—but the group is thinking globally.

In a groundbreaking deal, GDF Suez struck a partnership with the China Investment Corporation (CIC) across multiple businesses that will see CIC become a 30% stakeholder in GDF's international gas E&P business. Chief representative Raphael Schoentgen puts the matter simply: "We are of course also working to partner with Chinese companies outside of China. There are very large developments to be executed in the upstream gas industry and in power. We have to deliver gas to our markets and power to our clients, and we do it often with partners. Partnering is a way to share risks. When there is collaboration, not only are the risk shared, but also operations are executed better. Why not do it with Chinese partners?"

Think Locally

Atlas Copco's John Brookshire—former general manager of Compressor Technique in China, and current GM of the Compressor Technique Customer Center in the U.S.—and Kevin Illingworth, country manager of Expro China, on localizing a global company.

How does your organization adapt to the unique needs of the Chinese market?

John Brookshire: China is immensely important for our company.

We have 15 manufacturing facilities in China, and over five and a half thousand employees. We bring a lot of technology to China—but we also create technology in China. We have two R&D centers in this territory: one focused on mining and construction, and another focused on compressors. We bring our latest technologies to this market right away; otherwise, we develop them locally.

John Brookshire, former general manager, compressor technique China, Atlas Copco; Current general manager, U.S. Compressor Technique Customer Center, Atlas Copco

This region is extremely large, and diverse. We serve many of our traditional customers here—foreign international companies. These customers tend to buy the same products globally. However, if we only focused on our international clients, we would miss a huge portion of the market. Our business is changing, and we are focusing increasingly on local clients, and local content. Indeed we have recognized that, for domestic clients, needs can be different.

We address the challenge of local competition with what we call our 'multi-brand' strategy. Within the Group, we have different tiers of products that offer different value propositions for different levels of the market. These tiers range from the high to the low end. In China, for instance, we have already purchased three local compressor manufacturers. This allows us to offer a different cost structure, and a different value proposition, to align with the needs of customers who are not interested in our more expensive products.

Kevin Illingworth, country manager, Expro China

Kevin Illingworth: The China market is quite unique in terms of the way its national oil companies are structured. Sinopec, CNPC, and CNOOC each have individual subsidiary companies that are the equivalent of entities like Expro and Weatherford. There is hence a major domestic service provider presence, and the market is very difficult to penetrate—the NOCs prefer to give business to their own branch organizations.

Where we, as foreigners, can make a difference is in terms of new technologies and the experience we bring to the table. 10 or 15 years ago, Expro was trying to compete in China in very traditional niches. Today, Chinese companies are themselves very capable in those areas, and this avenue of business has largely gone away; now, we focus on areas where we can truly bring added value, such as cutting-edge technological segments.

Expro, as a company, is always very good at quickly reacting, and adapting, to customer needs. This offers us a competitive edge in the market. What does not change, however, is the fact that anywhere in the world, a company must understand what its clients want. You can only discern their needs with open, face-to-face communication.

Statoil's Ole Willumsen agrees. Some years ago, Statoil engaged in its first foreign partnership at the Lufeng-22 offshore block in China—and, as the company looks to renew its upstream engagement in the market, it is looking to strengthen its relationships through further conduits. Willumsen comments, "If we create cooperation with the Chinese NOCs internationally, it can create positive spill-over effects for our operations in China. Our operations abroad with the Chinese are very beneficial in that regard. We are deepening our relationship. Negotiating at the table is one thing, but really working on a project together is quite another. By doing that, we can enhance our mutual understanding."

BP's Chen Liming leaves his industry with the following thought: "If we look at the evolution of international investment into China, we see that the driving force has changed. In the early days, the pivotal force was money; later, management; later still, technology. The reality has continuously evolved—history has shown that it has evolved quite dramatically.

"In the same way, while one reason for partnership may phase out, another reason will emerge. We cannot say what will emerge in the future, but we are confident that good reasons will continue to incentivize multinationals and China's companies to work together."

China Inc.

It was not long ago that the international community watched CNOOC fail to enter the North American market with a takeover bid for Unocal. Five years later, the company bought one-third of Chesapeake Energy's investment in South Texas in what was the largest Chinese purchase of United States energy assets the world had ever seen. As deals like this and CIC's investment in GDF Suez take shape, 'China Inc.' continues to climb the international value chain.

Globalize

Sinopec chairman Fu Chengyu illustrates a developmental history that he shares with his colleagues at CNPC and CNOOC. "Sinopec," he says, "has implemented a 'Go Out' strategy for more than 10 years. The difficulties we faced at the beginning of this journey were innumerable! However, we have accumulated experience, and learned the value of persistence. It is thanks to this troubled past that we can be confident about our future."

Fu Chengyu, chairman, Sinopec

Through waves of acquisitions, Fu says that he began to pay attention to a maxim put forth by the consultancy McKinsey: "30% of the work is acquisition; 70% is integration." Chinese companies have had to modify their culture to succeed as global companies. Fu speaks of the "enterprise" culture that his organization has developed—a notion echoed by Chinese leaders throughout the industry. Like other international oil companies, today's Chinese NOCs are creative, bold, and unafraid to take risks.

Antonoil Multi-Stage Fracturing for Shale Gas Horizontal Well in Southwest China

CNOOC's Chen Wei Dong also notes a purely market-focused reasoning for China's international expansion: "Company growth, and energy supply security, are not the same. These are two trends on different tracks. And yet, ten years ago—and even now—many people thought that the Chinese are venturing to international markets to secure supply for the domestic market. This is not true!"

Many people believe, too, that the Chinese are going to foreign markets to bring expertise back home. Chen rejects this notion as well. In speaking about Chesapeake, Chen becomes animated: "We went to Texas—and, to speak of larger trends, Chinese NOCs are going outside China—in order to grow our business. We found that Chesapeake could benefit from our investment, and, because of the mature approach in the North American market, our profit margins could be higher. It is a matter of pure business! It is not a matter of bringing knowledge back to the country."

Innovate

Chinese companies are, too, expanding R&D programs with a new mind frame. Chen Wei Dong explains, "We are struggling with a bit of a philosophical question: should we, as CNOOC, focus solely on our own business, or conduct R&D for the greater sake of the country? If we look at the evolution of the multinationals, their growth has been driven by very much focusing on their own interests: when they develop some technology or equipment that is valuable on the market, they guard it very closely." In a break with the old mode, Chen is a firm believer that CNOOC should create intellectual property to serve its interests as a business, rather than its interests as a national company.

Chen Wei Dong, chief energy economist, CNOOC

Zhang Mi, chairman of Honghua Group—a business whose revenues already exceed half of a billion dollars after offering an IPO little more than four years ago—remarks on a very interesting turn of events—and one that, increasingly, is not unusual. It is a very recent memory that Chinese oilfield service companies purchased complex oilfield equipment from North America. Today, companies like Honghua are selling this same equipment right back to a North American audience, with technological development programs that increasingly rival Western competitors.

Zhang Mi, chairman & president, Honghua Group

Zhang tells Focus Reports that the evolution of his company "symbolizes the nation's own transition from 'Made in China' to 'Created in China.'"

A New Kind of Company from the Inside Out

China Oilfield Services Ltd. (COSL), a CNOOC subsidiary and the most prominent and successful of China's oilfield service enterprises, began life in the fragmented form of seven CNOOC divisions. Its technologies and equipment were modest and underdeveloped, and the organization focused solely on the local market.

In 2002, COSL restructured as a single entity and went public in Hong Kong (following in the footsteps of major NOC upstream subsidiaries such as CNOOC's own CNOOC Ltd.)—and its very character as a business began to undergo drastic change. As Li Yong, CEO and president, explains, part of the shift has been readily apparent to outside observers: company size more than doubled, reaching approximately 16,000 employees. Of these, the company took on over 2,000 international staff members from more than 30 countries. COSL came to own 34 drilling rigs, and developed 5 integrated R&D institutions.

Li Yong, ceo & president, China Oilfield Services Ltd. (COSL)

The company also went global, a decision Li explains was driven by two factors: "One stimulus was that, after going public, our investors needed to see the company successfully expand overseas in order to feel sure about their investment. However, this was not the most important reason we saw to expand. The more significant reason was that COSL owned a substantial amount of heavy equipment, and had made a large number of investments. In order to ensure return on these investments, we saw that we could not rely on a single market—such an approach was too risky. Hence, we began to internationalize." COSL is now present in major oil markets the world over, including in North and South America, the Middle East, Africa, Europe, South East Asia and Australia.

These are great measures of success; however, Li believes the greater transformation is internal: "During the years of our globalization, changes in revenue and market share have been very obvious. But I think the most notable difference is within our administrative team: the way we think and work has changed fundamentally. The ability of adapting and operating based on international standards is perhaps hard to observe from an outsiders' perspective, but I can confidently say that the inner power and quality of our company has grown tremendously.

"If we look at our company's history, we have been around for approximately 40 years. Even our restructuring story now has a 10-year history. And yet, we still think of ourselves as a very young company that is full of energy. Our entire team has a strong desire to develop the organization to greater heights."

Privatize

Honghua is far from the only private Chinese company to achieve distinction. The last five years have seen a major wave of IPOs from private Chinese petroleum players as they find increasing success. Some say private companies are the future of the industry in China.

James Ma, chairman of Antonoil International, the global arm of oilfield service enterprise Antonoil, says that his company closely models their practices on their study of successful multinationals. Initially, Antonoil followed China's NOCs overseas—something it called the 'follow up' strategy—a typical channel of expansion for China's private companies.

James Ma, chairman, Antonoil International

However, having established a presence in foreign markets, Antonoil found that it could expand its customer base, and do more than provide services for China's national organizations. Ma illustrates: "We went to Kazakhstan in 2008—we followed PetroChina to the market. However, after one or two years of business there, we had established an office, and had a number of full-time, local employees on site. We established a service base. It became more than a matter of 'follow up.' We began to communicate, arrange seminars, etc., with the national Kazakh oil company."

"We do not want to be a 'Chinese-international' company. We want to just be an 'international' company. As a company that wants to do business internationally, you should tune every aspect of your business towards international practices: culture, engineers, investors, company strategy, structure, business model, and etc. If Chinese companies want to become global, they must change their ideas. They must change their culture. I have seen many Chinese companies try to operate abroad the same way that they do in China—but this is not enough. This does not work for the long-term."

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com