An oil revolution is taking place in the US West and Mid-Continent

Fred Lawrence and Ron Planting, IPAA, Washington, DC

While the blockbuster plays in states such as Texas and North Dakota make the biggest headlines for increases in US crude oil production, there's no denying that developments in other states together add up to significant gains. Just like the other plays, many of these involved the technological advances of horizontal drilling and multi-stage hydraulic fracturing. The US map shown here indicates how widespread horizontal drilling has become.

Oil states

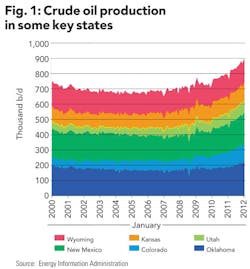

After North Dakota and Texas, there is a significant tier of states where crude oil production is increasing on a steady basis (See Figure 1). Six states in the western half of the US combined have increased US oil production by about 240,000 barrels per day (b/d) since early 2007. These include:

- Oklahoma – Crude oil production has risen about 70,000 b/d from January 2007 through February 2012 (the latest available from the Energy Information Administration).

- Colorado and New Mexico – Each saw increases of about 50,000 b/d over that period.

- Utah and Kansas – Each had 30,000 b/d increases.

- Wyoming – While Wyoming's net gain over the period was just 10,000 b/d, the state has seen a steady increase of twice that figure since bottoming out in mid-2009.

Since January 2007, these six states have increased crude oil production from a little more than 650,000 b/d to almost 900,000 b/d, an increase of nearly 37% collectively over a five-year span. This is roughly equivalent to the amount of oil produced by Colombia and Indonesia.

Sampling of plays

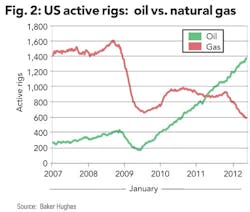

The plays behind these noteworthy state-level increases often cross state boundaries. Some are previously explored legacy areas that are getting new attention, while others are new plays or migrations into new geologic zones of older plays. With the already well-supplied natural gas market and the divergence of crude oil versus natural gas prices in the past few years, attention has been increasingly focused on applying the ideal drilling and completion technology to tap into liquids potential of areas that were originally natural gas-oriented plays, as natural gas drilling dominated US activity from 2004-2010 (See Figure 2).

One of the oldest producing states in this group is Kansas, with its first crude oil production in 1889. In fact, all six states have produced crude oil since 1911 or before. While for much of the past decade or so, rig activity in Kansas was tilted more towards natural gas than crude oil. However, in 2008 more wells were completed for oil than for natural gas. Currently, Kansas rig activity is overwhelmingly oil-oriented.

Besides shifts in oil/gas targets over time, there are disparities of activity geographically across the state, illustrating that state boundaries and geologic boundaries rarely coincide. Specifically, Kansas continues to be among the states with the largest number of rigs drilling traditional, vertical wells. At the same time, drilling activity in the southern part of the state has seen rising amounts of horizontal drilling over the past year or so.

That drilling trend reflects increasing interest in the Mississippian Lime, a target that stretches southward into northern Oklahoma. It's not that this boundary-crossing geographic region has not already been heavily drilled in in the past, but new technology has enabled commercial production from tighter/less porous Mississippian rocks below the "Chat." While, as the name suggests, the Mississippian Lime is a carbonate formation rather than shale, therefore fracturing combined with horizontal drilling is needed to make the Mississippian Lime economic.

Fracturing carbonates tends to be less intensive and less costly than for shale, and the region is also attractive for an oil/gas ratio reported to be above 50-50. Higher porosity, natural vertical fractures, and geologic knowledge gained from past activity also provide some potential advantages. As natural gas prices have weakened relative to crude oil and NGL prices over the past several years, operators have tended to target the more liquids-rich parts of the play.

While Oklahoma shares the Mississippian Lime play with Kansas, there are a number of other active plays in Oklahoma tied to the Woodford shale formation. These include the Cana in west central Oklahoma's Anadarko Basin and the Arkoma Basin in the east. As oil and natural gas prices have diverged, activity has shifted toward the Cana, which trends towards oil and liquids-rich gas, versus the more natural gas-oriented areas of the state. Although the Cana is one of the deepest commercial horizontal plays, it is also one of the more economic plays due to high volumes of condensates and other liquids.

The Granite Wash, a play with mixed oil and liquids-rich natural gas, touches Oklahoma's western border. While as a tight sands play it may have better porosity and permeability than shale, there is apparently much to be learned about its complex geology, which changes from point to point in sometimes unexpected ways.

For this play, still in its early stages, the majority of rig activity has been on the Texas side. Notably, one independent operator believes the Granite Wash could become the largest Lower 48 oil and gas field yielding as much as 114 barrels of oil equivalent (boe) over its lifespan (75% attributed to natural gas.)

Another border-crossing play is Bone Spring in the Delaware Basin, a play within the Permian Basin that extends from New Mexico's southeastern corner of the state into Texas. This is an oil play with multiple, stacked zones. Varied geology adds to the complexity of a play in its early stages.

The majority of horizontal activity in New Mexico is in this vicinity, though other parts of the Permian differ in approach as different technologies have been more successful for different areas. While there were approximately 180 horizontal permits issued around Bone Spring for all of 2010, roughly 400 permits have been issued before mid-year in 2012.

The Niobrara is targeted in both Colorado and Wyoming. In Colorado, producers focus on the Wattenberg field in the Denver-Julesburg Basin. The Wattenberg field, in the northeastern corner of the state, was discovered in 1970 and ranks as the 13th-largest oil field and 10th-largest natural gas field in the United States (2009 data from EIA). While operators focused earlier on producing natural gas and de-risking the play, horizontal drilling and multi-stage fracturing have spurred the migration toward NGLs and crude oil. Variability makes location important, as this is not a "blanket play."

While the Niobrara formation varies by location from chalk (marl) to shale, the underlying Codell is a sandstone. Both lie above the traditional "J-Sand" natural gas-producing zones in the Wattenberg and are often produced together. In El Paso County (Colorado Springs), exploratory drilling could extend the play southward. The same holds true in Routt and Moffat counties in northwest Colorado. Further north in Wyoming, the Niobrara and the Mowry are shale formations dependent upon recent, advanced technology. Before the advent of these technologies, they historically had not been as active for liquids. Experience is still shaping up in this play, with results varying by location and operators applying learned lessons in the more economic areas.

In Utah, horizontal drilling is concentrated in the Monument Butte and Central Basin area in the northeast corner of the state. This region lies within the Uinta Basin and is an oil play in sandstones of the Green River and Wasatch formations. One company has calculated the Uteland Butte's net resource potential at nearly 300 million boe, and its production from the Greater Monument Butte field has grown more than 300% between 2004 and 2011. Thanks to progress in Utah, the oil production in that state has almost doubled between 2002 and 2011, according to the EIA.

Broad trends

By no means is this a comprehensive survey of US liquids plays, but rather a sample of a complex, unfolding story in these states. Nevertheless, there are broader trends apparent. First, the application of horizontal drilling and multi-stage fracturing is an industry-wide trend reaching into many regions of the country, both in areas that have seen a long history of oil and gas activity as well as newer plays.

Second, reflecting in part the divergence in oil and natural gas prices, there has been a trend toward oil over natural gas plays, and liquids-rich gas plays over dry natural gas. These states continue to substantially boost US oil and gas production and will show robust increases year by year based on their impressive potential.

These broader trends should not obscure the fact that each of these plays is different. Keying in on the various technologies required to meet the challenges for each of these unique plays is still at an early stage. Variability abounds in the composition of formations (shale, sandstone, chalk, etc.), their complexity, natural fractures, thermal maturity, proneness to oil, gas, and NGLs, and the degree of existing geologic experience in these areas. Indeed, the breadth and diversity of the application of this new technology is the mark of a watershed innovation, and independent producers continue to be at the vanguard.

To review our past analyses and our latest data, please visit the Resources section of www.oilindependents.org.

About the authors

Fred Lawrence is vice president of economics and international affairs for the Independent Petroleum Association of America. Ron Planting also serves on the IPAA's economics team.

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com