Oil and gas derivatives - why use them and how to avoid margin calls

A. Stephen Kennedy

Amegy Bank of Texas

Houston

With oil and natural gas prices levitating to record highs, who would have dreamed that such prices could actually be a problem for some oil and gas producers? But for many who hedged some of their production at lower prices, that’s exactly what they have-a Texas-sized problem called margin calls. But before examining why this is happening and how margin calls can be avoided, let’s briefly cover what energy derivatives are and why producers use them to hedge oil and natural gas prices.

Energy derivatives are typically comprised of one or more of three instruments: call options, put options, and swaps. Calls (ceilings) and puts (floors) can be arranged to form collars -costless and otherwise. Some collars, known as participating collars, have provisions that allow the producer to participate in a portion of the upside (i.e., when the market price moves above the ceiling). Others may have disappearing ceilings, known as knock-outs. Or a producer may choose a simple swap, which usually means that he is swapping a floating market price for a fixed price.

Why would a producer want to hedge his production? There are several reasons: to lock-in current prices to ensure that fiscal 2006 cash flow covers expenditures budgeted for 2006; to maximize debt for acquisition financing; or he may forecast lower oil and gas prices and want to lock-in current prices to protect himself and his employees (i.e., his overhead) against the repercussions of a precipitous drop in cash flow.

Covering the 2006 drilling budget

With drilling rigs in short supply and drillers demanding multi-well drilling contracts to work for a producer, producers are being forced to make significant commitments for the coming year or be sidelined while others get their shot at adding reserves via the drill bit. The problem that producers have with making substantial drilling commitments is that they remember what happened to the price of oil in 1998 and to the price of natural gas in 2001.

On December 18, 1997, the oil futures strip for calendar 1998 (the average of 1998’s 12 monthly futures contracts) was $19.10/bbl. But the average price actually received in 1998 was $14.39/bbl. On December 21, 2000, the natural gas futures strip for calendar 2001 was $6.29/mcf. But the average price actually received in 2001 was $4.04/mcf.

This recent memory, by the way, is most likely the reason that oil and gas producers did not dramatically raise their 2004 drilling budgets at the end of 2003, even though oil and gas prices were expected to be higher in 2004, versus the previous year. But in 2004, producers did not have to worry much about drilling rig availability, like they do now.

So, with their hand being forced by high rig utilization rates, many producers realize that they need to commit to a sizable 2006 program to get and keep drilling rigs. To protect themselves while making such a commitment, many are hedging a portion of their 2006 production to lock-in enough cash flow to cover those expenditures.

Financing the acquisition

Acquisitions of oil and gas properties slowed in 2002 and 2003, as oil and gas prices increased but memories of recent low prices remained. During that time, many buyers complained that they could not meet sellers’ price expectations, which were, understandably, optimistic. Besides, would-be sellers were enjoying a nice increase in cash flow and were in no hurry to sell.

Oil and gas futures contacts were backward-dated during that time, meaning that the near-term price was higher than the prices expected further out on the time horizon. But during 2004, the futures curve began to flatten out, bringing long-term prices higher and much closer to that of the near term. The futures market was beginning to reflect the belief that the fundamental supply/demand picture for oil and gas had changed and that prices were likely to stay high for quite some time.

This change in the oil and gas futures curve gave buyers something with which to work-they hedged the price of the acquired production and were finally able to meet seller’s demands for higher acquisition prices.

As everyone knows, equity to fund acquisitions doesn’t come cheaply. To minimize the use of expensive third-party equity and maximize management’s return, low-cost bank debt should comprise as much of the buyer’s capital structure as possible.

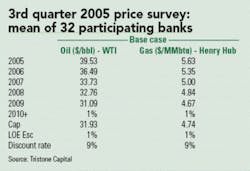

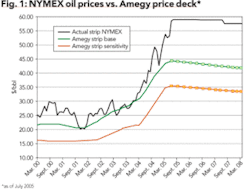

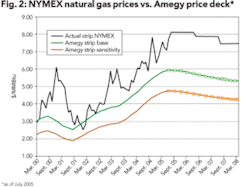

The dilemma-how does one maximize bank debt when bank price assumptions for oil and gas are running 30 percent to 40 percent lower than market expectations (see Fig. 1 and Fig. 2)? The obvious answer -hedge the prices, enabling banks to lend more than they would be able to using their standard price decks.

That’s precisely what many producers did during 2004. While they hedged primarily to close acquisitions, many couldn’t help but wonder if they might also be catching the top of the energy price cycle. Sometime later, it became all too clear that was not the case.

Just as the producer is reminding himself how satisfied he is with his underwater hedge prices-can make a nice return at that price, etc.-the phone rings. On the other end of the line is his hedge counterparty who is dialing for dollars-margin call dollars, that is. Now that market prices have headed north of the swap price (or the ceiling price of a collar, whichever the case might be), the producer has a liability to the counterparty and the counterparty wants collateral to protect itself in the event that the producer doesn’t pay.

The ability to call for this protection is covered in the standard operative agreement for derivative transactions, known an ISDA. These margin calls are usually satisfied when the producer provides the counterparty with one of three things: 1) a cash deposit; 2) a letter of credit or 3) a first lien on the producer’s oil and gas properties.

If the counterparty is not the producer’s bank or an affiliate of its bank, the producer may find it difficult to work out a pledge of his oil and gas properties. The counterparty will likely not want to take a second lien on the properties-behind the bank’s lien. Instead, it will ask to be in a pari passu (side by side) collateral position with the bank. For such an arrangement, a fairly complicated negotiation and agreement over terms must take place.

In many cases, these terms govern the rights of each party to do certain things with the producer, like: 1) commit more credit; 2) receive payments; 3) restructure obligations; 4) foreclose on assets and 5) liquidate collateral. The resulting agreement between the bank and the non-bank counterparty is called an Intercreditor Agreement.

Since it is somewhat difficult for the two parties to agree on these terms, quite often no agreement can be reached. This leaves the producer with the option of posting cash with the counterparty or issuing a letter of credit. Since both the opportunity cost of cash and the cost of borrowing are typically higher than the cost of a letter of credit (“L/C”), the producer will usually ask his bank to issue a L/C on his behalf.

But with oil and gas prices headed steadily higher, the margin calls and the L/C issuances have been coming at an alarming rate. In one case, a producer that entered into an oil hedge in May of 2005 initially posted a $2.5 million L/C to its non-bank counterparty. That counterparty has now made three margin calls and currently holds $15 million of L/Cs issued on behalf of that producer.

Incidentally, this does not come without cost, as mentioned previously, since the charge for issuing a L/C usually ranges from 1 percent to 2 percent of its face amount. And at the writing of this article, hurricane Katrina is slamming into the Gulf region, disrupting oil and gas flows and driving the price of oil to more than $70/bbl for the first time in history. One has to wonder if this producer will get yet another margin call tomorrow morning.

Avoiding margin calls

Can producers avoid these margin calls? They can-if their lender is also their hedge counterparty. Many banks now offer their services as energy derivatives counterparties. Some have developed their own software to estimate, book, and track derivative risk-spending more than $1 million getting set-up for business.

Others are using off-the-shelf software solutions that are less expensive, such as Kiodex Risk Workbench®. Why are banks spending money to get into the energy derivative business? Well, of course, one reason is clearly to make a profit. Another reason is to assist the producer in executing oil and gas hedges in a manner that eliminates the need for margin calls.

By combining loans and energy derivatives, a bank can use the same collateral-the producer’s oil and gas properties-to cover risks associated with both transactions. As the value of the derivative to the counterparty increases, so does the value of the collateral that secures it. In fact, if only a portion of a producer’s production is hedged, the value of the collateral actually increases faster than the value of the derivative. In that case, a bank counterparty would only be concerned if a producer’s physical production volumes were not at least equal to the volumes that producer hedged. If they were not, the producer might have to come out of pocket with cash to satisfy his obligation under the derivative contract-rather than just passing on a portion of the cash flow from physical sales to the counterparty.

There is also the question of total risk exposure. How much risk exposure does a bank want to any given producer? Since some banks consider L/Cs to be more akin to a loan than to the “soft exposure” incurred while acting as counterparty under a derivative contract, they are more likely to set a lower limit for L/C exposure to a given producer, versus the derivative exposure to that same producer.

Why would there be any difference between the two? The main reason-the capital a bank is required to hold against derivative exposure is half, and in some cases less than half, of the capital that it must hold against L/C exposure.

So, does this mean that producers should not hedge with non-bank counterparties? No, not at all. But because the current oil and gas price environment that we find ourselves in is more volatile than it has been in the past, a producer should consider how he will meet margin calls, if he chooses to deal with a non-bank derivative counterparty, and what the cost of those margin calls will be.

For producers that have a lot of unsecured credit with non-bank counterparties or that have plenty of cash to be posted as collateral, it is not a concern. Producers who do not may want to consider a different course.

In the final analysis, the old cliché-“this is a high-class problem to have”-certainly comes to mind. It sure beats trying to figure out how to offset low oil and gas prices by cutting back on salaries, pipe dope, and rubber gaskets to make financial ends meet. OGFJ

The author

A. Stephen Kennedy [steve.kennedy

@amegybank.com] is a senior vice president and manager of Amegy Bank of Texas’ Energy Lending Division, which he formed in 1997. Prior to beginning his energy banking career in 1986, he was managing partner of a family-owned oil and gas company.