Upstream technology review useful for improving E&P performance

George Kronman and Rick MauroLandmark

Consulting & Services Halliburton Digital & Consulting Solutions Division

Houston

Efficiency can make or break an organization. While massive amounts of money have been poured into technology and IT initiatives in the oil and gas industry in recent years, spending alone does not make a company more efficient or assure greater productivity.

Today’s E&P professionals spend an enormous amount of time sifting through mountains of increasingly complex data, juggling dozens of poorly integrated software tools, and wandering through labyrinths of workarounds in an effort to get their jobs done. Convincing these employees to adopt new technologies and approaches to improve their efficiency in finding, developing, and producing oil and gas is a challenge as well.

Many problems exist in the use and deployment of technology at all levels of an organization, but it is often difficult to get a macro view of the whole picture. What may be needed is a fresh approach from unbiased outside consultants who can team up with the company’s own in-house professionals to tackle such complex issues by launching a global upstream technology review (UTR) aimed at better aligning the company’s technology, people, and processes with critical business objectives.

Once an organization decides to take a comprehensive, cross-disciplinary look at how it is using - and misusing - technology, it will learn quickly enough how digital technology issues can have a significant impact on the bottom line.

An upstream technology review is a structured, yet highly flexible methodology that any E&P company can use to assess and improve the way digital technology, infrastructure, data issues, workflows, people skills, and knowledge are being applied to help them achieve their business goals.

The UTR can focus on one discipline (e.g., reservoir engineering) or provide an integrated multidisciplinary view across the oil and gas lifecycle (exploration, field development, drilling and completions, production operations, and data management). It can be applied at any level within an organization - from a single team, asset, division or business unit to the entire corporation. The methodology supports the need to improve and drive greater efficiency in the E&P value creation process.

How, exactly, does a successful UTR work, and what’s the potential payoff? To illustrate, let’s walk through the process in detail as it was implemented at a hypothetical company called Global E&P.

Overview of the UTR process

A UTR is an interview-based approach that begins with the executive sponsor or sponsors, generally senior management and vice presidents of E&P, IT and/or Operations. Consultants meet with executives to flesh out the issues that haunt them in an effort to better understand their major business goals, and determine the scope of the review.

In Global’s case, senior management wanted to assess the utilization of digital technology across E&P operations worldwide and seek recommendations for improvement. Their highest-impact, three- to five-year business objectives were to accelerate prospect generation, increase personnel productivity, shorten time to first oil, and optimize production.

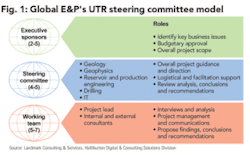

To execute the UTR process collaboratively, a five-member, full-time core team of consultants and internal experts was established under the oversight of a steering committee of senior technology and discipline managers (see Figure 1). Furthermore, a 15-member cross-functional UTR facilitation team including representatives from multiple operating units was actively engaged in the project.

After meeting with the sponsors, the core team conducted interviews with division managers, bringing everyone with common challenges into the room at the same time so they could build on one another’s observations. Again, interview questions were aimed at identifying key business drivers and major technological challenges - quantitatively, wherever possible.

Interestingly, at times, they were unable to do so. Many could only describe their goals in very general terms - for example, to generate more prospects. All comments were recorded, without judgment, as part of the discovery process. Vendor neutrality regarding software or hardware products was rigorously maintained.

Over roughly a four-month period, 50 E&P teams, including more than 300 geoscientists, reservoir engineers, petrophysicists, drillers, production engineers, landmen/negotiators, economists, technologists, and data management support people in several countries, were interviewed. Qualitative and quantitative questions were asked to determine:

• specific team business goals and deliverables;

• what the teams did on a daily basis;

• whom within the organization they interacted with (e.g., support needs and “handoffs”);

• what data/databases, digital tools, and workflows were used and any issues surrounding them;

• where they encountered pitfalls and bottlenecks; and

• what improvements they felt were necessary.

In two to four hours, interviews took teams through all the workflows they normally followed to achieve the business goals set for them.

Facilitation of interview sessions like these requires a special skill and sensitivity that takes time and considerable experience to develop. Once people understand the purpose is not to make anyone appear incompetent or weed out poor performers, passions start to flow. All kinds of frustrating software, data, infrastructure, training, and support issues come out. Interviewers capture them on flip charts, whiteboards, and laptops.

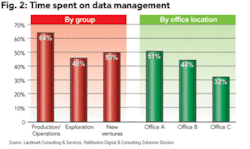

Based on all this input, current state workflows are mapped, noting gaps, inefficiencies, and best practices, and returned to teams for validation. With some teams, supplemental surveys were filled out to assess change readiness and time spent doing selected activities (see Figure 2).

“Data points,” or factual statements, collected during interviews are entered into a unique proprietary software program for analysis. Data points might be anything from “This software drives me nuts because I can’t properly color-code seismic attributes” to “I can’t share well information with the engineer because he’s using a different database.”

Consultants carefully sort these data into findings, and findings into conclusions, in order to develop recommendations and action plans. “Findings” are summary statements based on many data points that describe a problem or opportunity, for example: “Current geophysical software is not meeting the team’s needs.”

A “conclusion” is a significant cause-and-effect observation, based on findings, for example: “Geologists have trouble using software because they have not been adequately trained.”

Finally, conclusions are rolled up into specific recommendations for improvement. The advantage of this hierarchical approach is that every recommendation and conclusion can be mapped back to the specific data points and teams from which they are derived, providing an audit trail and the ability to test the recommendations. Once interviews are completed and results verified by the teams, the UTR core team reports back to the steering committee and sponsors.

At Global E&P, more than 10,000 data points were gathered and rolled up into 270 findings, 14 high-level conclusions, and ultimately six detailed recommendations for long-term improvement. A number of urgent, easy-to-fix issues (“quick hits”) were also identified and captured during the interview process.

Outcomes of the UTR Process

What did the UTR turn up at Global E&P? Every one of the 50 teams raised data management concerns, regardless of technical discipline or geographic location. Lost time analysis revealed that E&P professionals spent from 32 to 64 percent of their time finding, moving, reformatting, loading, quality-controlling, and otherwise dealing with data (see Figure 2).

Amazingly, despite all the recent advancements in digital technology within the upstream industry, this number is almost exactly what oil companies were saying more than a decade ago. Global E&P, like most of its peers, lacked both a coherent data management strategy and a universal digital technology strategy.

Part of the problem was “software chaos” in which teams were utilizing multiple, redundant software applications for different steps of their workflows. In the absence of a common strategy, technologies had been adopted based on individual preferences and ease-of-use, rather than functionality or integration with other tools. As a result, inconsistent databases had proliferated and team members were unable to share digital data with others, either within their own teams or among other groups working the same asset or trend.

Ostensibly collaborative workflows became increasingly complicated workarounds, eating up precious interpretation time, undermining trust, and costing inordinate amounts of money on inefficient field operations. One team estimated, for example, that poor cooperation between geoscientists and drilling engineers on new well locations was costing an extra $250 million - every drilling season.

What’s more, the upstream technology review identified more than 50 different IT initiatives currently underway in various departments and regions across the company, many of which were overlapping or being done in specific offices. Lack of global coordination and integration had resulted in redundancy, inefficiency, and needless costs.

Global E&P decided to implement the UTR recommendations based on business priority. Implementation began by developing an E&P digital technology strategy (DTS), adopting an integrated database management strategy (DMS), conducting pilot projects to demonstrate immediate value, and resolving “quick hit” issues that were creating frustration and unacceptable downtime. Other recommendations were to be addressed as well.

The DTS incorporates a future vision and common approach to digital data, software, standards and workflows across E&P specifically focused on finding, developing, and producing oil and gas more effectively and efficiently in alignment with the corporate strategy.

Major elements of Global E&P’s DTS can include:

• adopting standard E&P databases, from which all applications read and write;

• creating standard processes for E&P data storage, retrieval, and archival;

• buying off-the-shelf versus building digital technology wherever possible;

• promoting integrated workflows and volume-based interpretations;

• creating guidelines for future software purchase and integration; and

• training personnel to keep their knowledge consistent with best practices.

Global E&P’s data management strategy, which was intimately related to its corporate DTS, included:

• establishing clear accountability, ownership, and processes around the data life cycle;

• developing a hierarchical architecture for data storage within corporate, master, and project-level databases;

• adopting an integrated project-level database for geoscientists and engineers;

• integrating application suites with data models; and

• standardizing naming conventions and taxonomy.

To test these new approaches and provide a working “lab” prior to widespread rollout, several pilot projects were implemented. In one case, a newly formed asset team had just received new 3D seismic data. It was imperative that they get up to speed and establish optimum communications as quickly as possible.

They successfully adopted a common G&G data store, developed integrated interpretation workflows, outlined procedures to maintain clean data and support users, and clarified team roles, responsibilities, and collaborative processes. Application of the right technologies for the right problems greatly reduced cycle time and improved the team’s bottom line.

Although long-term business value is still being tracked, several key benefits are expected directly and indirectly at Global E&P from the UTR:

• Cycle time reduction of 15 to 30 percent for all GG&E professionals resulting from better data management is estimated to provide opportunity cost savings ranging from $11 to 21 million per year.

• Additional value-creation time and improved efficiency associated with exploration, field development, and drilling could contribute to increasing reserves anywhere from 67 to 133 million BOE.

• Minimizing data management time for engineers could accelerate the cycle from discovery to first oil, resulting in five-year NPV increases between $129 and 233 million.

Aligning technology, corporate goals

Global E&P is just one example of the challenges and benefits of an upstream technology review. Implementation of UTRs in oil and gas companies worldwide has shown that few organizations even come close to state-of-the-art utilization of their digital tools, data and personnel. Often, large gaps exist between vision and reality. Inefficiencies can seriously undermine value creation.

Too many silos still exist between disciplines, databases, and applications. Lack of shared earth modeling means interpretation is fragmented, and professionals waste excessive amounts of time dealing with data issues. Workflows are often too complex either for new hires or experienced professionals. Frequent personnel transfers are painful because people have to “reinvent the wheel” every time they move to a different office or asset team. Training is often out of sync with actual user needs, both in terms of timing and content.

What’s more, few teams apply early economic and risk analysis to determine where to focus their efforts to bring the greatest return on investment. The result is serious misalignment between what management hopes to achieve and what knowledge workers are doing on a day-to-day basis.

One of the best ways to realign digital technology with corporate goals is by conducting a thorough UTR to understand the current state and by developing a digital technology vision and strategy to define the future state. Oil and gas companies often have similar business drivers, but differences in asset portfolios, legacy systems, people, and operational problems.

The UTR is flexible enough to address variations within all of these facets of a company and provide solid recommendations leading to an effective E&P digital strategy. Companies that utilize their resources more efficiently can perform better than their peers, which makes it more likely they will achieve their financial goals as well. OGFJ

About the authors

George Kronman is director of prospect generation and field development for the Landmark Consulting & Services group of the Halliburton Digital Consulting and Solutions division. Since 1993, the field development practice group has completed more than 500 projects for oil companies worldwide. Prior to joining Landmark, Kronman was a senior manager in the energy consulting group at Andersen and spent 17 years with Amoco in a variety of technical, business, and management roles. He has an MBA from the University of Houston and a BS and MS in geology from the State University of New York.

Rick Mauro is director of the upstream technology review (UTR) practice for the Landmark Consulting & Services group of the Halliburton Digital Consulting and Solutions division. This practice is dedicated to delivering global UTR engagements, from corporate to asset team scale. Prior to joining Landmark, Mauro was a senior staff geologist with Mobil for 14 years, working in exploration and technical computing roles. He has a BS in geology from the University of Rochester.