An approach for sustaining Sarbanes-Oxley compliance

Steve Hill

KPMG LLP

Dallas

With the first year for compliance with Section 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act completed, many senior executives have reflected at length on the demanding effort that was required.

Apart from the sizeable commitment of necessary financial resources, the effort to comply with Section 404 and other key sections of the act required the time and attention of numerous employees, many of whom were asked to delay work on other projects to meet compliance requirements.

As companies move into year two and the years of compliance ahead, they recognize that the intense, costly, project-oriented focus that prevailed in year one is likely inappropriate and unsustainable over time. At the same time, many of them acknowledge that the intensity of their organizations’ focus on the issue is likely to diminish once deadlines pass and new priorities emerge. Consequently, they know they risk the erosion of first-year efforts if they do not find a way to sustain ongoing compliance effectively.

Enhancing the compliance effort in the coming years should be a key priority for any oil and gas company today. The process, however, will not be perfected overnight, but will evolve and mature in response to the prevailing business environment.

Over time, the compliance process should become increasingly cost effective and less risky. To reach this goal, companies should consider and then map out their best path toward compliance efficiency in the years ahead.

Creating the foundation

In addition to the routine documentation, testing, and remediation efforts from year one, to develop and implement an ongoing compliance program, organizations should capture relevant business changes or trigger events that could affect their internal control environment - events that could, in turn, affect compliance activities. Some examples of business changes that could impact compliance include:

• increasing volatility in commodity prices;

• acquisitions and divestitures;

• IT system implementations;

• new regulations;

• significant personnel changes;

• outsourcing; and

• entering or exiting markets.

Updating Controls

When they identify a significant business change, oil and gas company executives should analyze how it could impact internal controls and the controls environment. As the controls environment changes, senior management should measure the impact the changes have on their people, processes, technology, and the organization as a whole. For example, sustained higher commodity prices may lead some companies to adopt new hedging strategies in an attempt to protect margins.

These new strategies may require changes in mid- and back-office controls and procedures. Management can then plan appropriate financial and staffing resources as well as a timeframe in which to implement needed corrective measures to the affected controls.

Clear employee roles, responsibilities, and training for managing this remediation activity should be established and communicated to keep compliance activities on track. Management should eliminate and replace the ineffective controls. Existing documentation should also be updated to reflect the new controls.

Testing effectiveness

With a new system of controls in place, analyzing control effectiveness should begin with a formal plan that includes testing locations, timing, scope, and financial/staffing resources. Testing results should be consolidated and companies should prioritize gaps in control before carrying out further remediation. Special consideration should be given to offshore and international locations where testing requirements are not as easy to determine.

Any significant deficiencies or material weaknesses identified should be brought to the attention of the audit committee, external auditors, and other appropriate parties, and all results should be certified with the Securities and Exchange Commission. New controls testing documentation should also be archived for future reference.

These activities should be performed regularly throughout the compliance process by all aspects of the business, including finance, operations, and compliance-dedicated units.

Four steps to sustainability

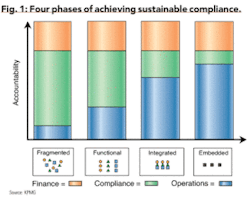

Companies working to reduce risk and cost can progress along four key phases for sustaining compliance: fragmented, functional, integrated and embedded. Gradually, accountability for the activities identified above should shift away from the compliance and finance functions toward operations (Fig. 1).

For an E&P company or pipeline this would mean implementing more upfront controls over activities such as measurement and reducing reliance on detective controls within accounting. This, in turn, should also help reduce the number and magnitude of prior-period adjustments (PPAs) related to operational errors or delays.

The fragmented phase is project-centric, in which compliance is achieved largely through disconnected efforts throughout the enterprise. Many organizations today are in this phase.

Extensive coordination and work are required by a centralized project management function. The finance operation temporarily establishes cross-business project teams that disseminate instructions, templates, and training for monitoring compliance efforts on an ad hoc basis. The teams also communicate, perform, and verify tests of internal control over financial reporting.

The functional phase is program-centric, in which compliance is achieved through a dedicated and focused team. These individuals are solely responsible for compliance-related activities and performance.

A centralized office function headed by a compliance leader, such as a chief compliance officer, chief risk officer, or designated internal audit manager, is established and process owners are identified. The compliance officer implements standard guidance, templates and training, and technology to assist in managing the compliance program. Compliance is routinely monitored and reported, and internal control over financial reporting is tested and verified.

For example, one midstream company has implemented a cross-functional continuous improvement team responsible for control rationalization - from the initiation of a transaction through financial reporting. Representatives from measurement, contracts, accounting, gathering, transportation, and processing gather bi-weekly for two hours to walk through the various contract types, identifying process and control inefficiencies, and improving overall communication and customer service.

The integrated phase is process-centric. Compliance is achieved in a fundamentally new way - by building compliance activities and procedures into existing business processes and technology. The goal is to allow the business owners to start to share responsibility for compliance. Internal audit, or another centralized compliance function, helps to oversee and support verification and quality assurance to help ensure compliance is achieved throughout the business.

Process owners with centralized oversight retained by a compliance function also assume more accountability in this phase. This centralized compliance function implements standard guidance, templates, training, and technology solutions to align business processes with compliance requirements. Supported by analysis and reporting from the process owners, this new office monitors compliance as well as tests and verifies internal control over financial reporting.

As an example, a large integrated energy company recently met initial Sarbanes-Oxley requirements and learned during this process that IT controls posed a significant resource constraint and risk to the “compliance” team. The company assigned responsibility to identify control changes and correct deficiencies to its chief information officer. The CIO responded by updating the IT system development process to include an analysis of changes to the control environment.

When implementing new systems or control-environment changes, the IT team would also be responsible for updating documentation and testing plans and communicating the information to the right people. By giving the CIO ownership of this task, the company will be able to integrate compliance into key steps of the IT system development process, thus gaining benefits from a more efficient compliance process.

The embedded phase is where compliance becomes part of organizational culture. It’s how business is done. There is a change in mindset, in which compliance occurs not only for the sake of meeting regulatory obligations, but also because it is the right thing to do. Accountability is instilled within the day-to-day actions and responsibilities of every individual. Internal audit, or other similar compliance function, oversees quality assurance for achieving ongoing compliance.

Achieving new efficiencies

Senior management can expedite the sustainability process by seeking to understand how compliance can evolve and what this evolution could mean for their business. For companies still in the fragmented phase, the compliance journey to the embedded phase can seem daunting. The key to getting started is to focus on the activities for sustaining compliance described above and then to put in place an implementation plan for evolving through the four phases that balances risks and costs over time. OGFJ

The author

Steven Hill is KPMG LLP’s national principle-in-charge for the firm’s Risk Advisory Services practice and is based in Dallas. KPMG LLP is an audit, tax, and advisory firm that is the US member firm of KPMG International. KPMG International’s member firms have nearly 100,000 professionals, including 6,800 partners, in 148 countries.