Finding alternative funding sources for sub-Wall Street O&G companies

Steven D. King

PetroInvest Houston

Private oil and gas companies drill the majority of domestic wells each year, but for the most part they fly below Wall Street’s radar screen. These 700-plus sub-Wall Street firms include all but the largest of the private firms, as well as the smallest of the publicly traded firms.

As Scott Johnson of Weisser, Johnson & Co. pointed out in his article in this space last September, these micro-cap (sometimes more correctly labeled no-cap) firms aren’t sharing in the increased availability of Wall Street’s capital. But these are the firms doing the heavy work, drilling about half of all domestic wells each year - and they are the companies that need funding the most.

So, how do they go about funding projects? Internal cash flow, plus family and friends is the usual start. We all know that, outside of just being lucky, companies can’t flourish if they don’t drill enough wells each year to make the statistical probabilities work. Unfortunately, the friendly money is usually insufficient to accomplish this.

As a result, this often means selling the rest of the prospect to the industry. By “the industry,” I am referring to the small group of very knowledgeable, drilling capital providers, ranging from individuals up to the larger O&G companies. They are willing to fund drilling projects - but at a stiff price.

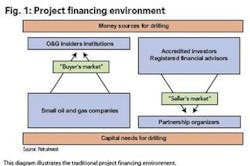

It’s a problem of too many people chasing too few as shown on the left side of Fig.1. And it’s the few who get the better part of the deal. A third for a quarter at casing point is really a tough deal for the prospect organizer who has to come up with his 25 percent of completion costs and development wells.

When all is said and done, the project generators and organizers don’t retain enough working interest to build that pool of capital that allows the self-funding of future projects.

Accessing non-petroleum money

There is another source of funds shown on the right side of Fig.1 that a few O&G companies have learned to rely on. Most interestingly, it could dwarf the size of professional monies available to the larger oil and gas companies.

Last year, more than $500 million was raised for drilling from accredited investors represented by their non-petroleum securities brokers. These aren’t the “boiler-room” operators. Instead, they are traditional full-service brokers with established high net worth clients.

The current amount raised is a drop in the bucket of total discretionary funds floating around Wall Street. Even a five-fold increase would only be a few drops in the bucket. Still, this funding source should, in effect, be considered unlimited.

Most of us with gray hair remember, with some uneasiness, when limited partnerships gave the petroleum industry a black eye during the ‘80s. Looking back now, there was nothing wrong in the theory - it was just that those executing it were lacking.

Companies willing to provide fair economic returns to the investor today, instead of just tax breaks, would discover a readily available source of funds probably at better terms than they currently get from their traditional sources.

Upsides and downsides

As with anything there are pros and cons. But first, let’s define partnerships. I use the term in a loose sense to include joint ventures, limited partnerships, and general partnerships that convert to limited after the wells are drilled. The common characteristic is that it is directed to the non-petroleum investor. Your securities attorney can best advise you on the subtle differences between these alternative business forms.

A large number of investors versus a few industry partners: At first this may seem to be a negative for partnerships, but not necessarily. Selling to the petroleum industry often means losing operatorship. Even as operator, getting 100 percent agreement on future activities can sometimes be a problem. Priorities shift - capital constraints happen just when you want to develop the discovery - threatening your company’s bottom line.

With a partnership, you have effectively farmed out to a working interest partner your control. Of course you have fiduciary responsibilities, but you are the general manager with the partners’ power of attorney. This gives you greater operational and pricing efficiencies.

Securities regulations versus doing it the way everyone else does: The fear of the unknown (i.e. the securities environment) has kept many oil and gas companies from using this financing option. Yes, there are differences, especially during the selling phase of fund raising. Generally, if you under promise and over deliver, with an abundance of pro-active communication, you will keep out of trouble. Just because the other O&G company down the hall always uses “the industry” doesn’t mean it has really evaluated the alternatives.

By using specialized partnership securities attorneys to set up the partnership and by establishing a strong administration support team (or by contracting with a suitable outside provider), you can avoid most headaches.

Initial cost versus cost of capital: Raising capital through the non-petroleum brokerage firms does require an initial investment in fund raising. But you should expect a better deal than you could get from farming out to an industry investor.

Oil and gas firms that decide to set up their own brokerage firm, effectively a captive broker/dealer who sells your partnership(s) exclusively, experience the highest initial costs - more than a million dollars before the first dollar is raised. The ongoing costs can be steep, as evidenced from the annual reports of the few public companies currently using partnerships. There is also a danger that your captive broker/dealer becomes a boiler-room operation.

There are lower cost alternatives.

You could hire a wholesaler, either an individual or a managing broker-dealer firm, to round up enough selling brokers. Using an individual often results in better than petroleum industry terms, but the initial investment can still be half a million dollars. Using a managing broker/dealer is faster, and therefore a little cheaper, since some of the partnership will be sold through that firm. But they usually take a bigger part of the upside of the deal, leaving you with only a standard industry deal.

An alternative approach

Do-it-yourself: A lower cost alternative is to do more of the organization of the selling syndication of independent broker/dealers yourself. However, unless you are very experienced with partnerships, doing it yourself might inadvertently run you afoul of securities regulations. And on top of that, you would not be getting a better than industry deal.

Even if you have stayed in compliance, setting up several independent broker-dealers as non-operating working interest owners under an AAPL Form 610 Operating Agreement still doesn’t protect you from violations these firms might make. Each broker-dealer writes its own offering memorandum, selling it, and acting as partnership general manager, all without your supervision. You are still part of the picture and in the line of fire if any broker-dealer violates securities regulations.

All the above alternatives, from your own captive broker-dealer to the do-it-yourself approach, have been perfected over the last 25 years, but they still rely on the shoe leather method of selling.

Using a finder service: The newest variation on the do-it-yourself approach is to use the internet to find interested brokers willing to sell your partnership. There are 5,500 firms employing 600,000 brokers to be connected to over 1000 sub-Wall Street oil and gas companies.

This service should also help you avoid securities regulation blunders and should know the other specialized professions you need. You control the offering and draft the documents instead of letting each broker-dealer act independently. You are the partnership general manager and the organizer of a single selling group.

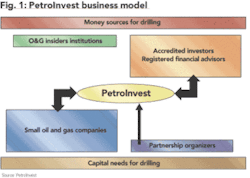

All combined, you should be able to keep your upfront costs down, get better than industry terms, and avoid regulatory headaches. PetroInvest LLC was founded to develop this business plan, Fig.2.

Conclusion

Raising drilling capital is often considered a necessary evil if a prospect is to become a producing property. Often oil and gas professionals skimp investing enough upfront money and effort on fund raising because they just don’t enjoy it. And when they do turn their attention to it, they do it the way everyone else does, often with the same results - the capital provider gets the cream off the top.

Raising money through partnerships is a viable alternative source of drilling capital. Many large independents, such as Apache and Swift, used this model during an early stage of their growth. A small handful of public companies and a larger number of private companies use them today to raise all their drilling capital.

Many more oil and gas companies could use this method. They have hesitated because (pick one or more): 1) their contemporaries don’t use partnerships; 2) fear of the securities regulators; 3) the initial start-up costs; and/or 4) becoming associated with a “boiler-room” broker-dealer.

These potential problems can be minimized by hiring the right professionals and possibly by using the internet. And your payoff can be substantial - not only from better terms, but also by getting more wells drilled because there is more capital available.

Think of partnership funding not as a complete replacement to your traditional outside capital sources, but as an additional source. OGFJ

The author

Steven King [[email protected]] is the founder of PetroInvest LLC, the Private Placement Drilling Program Exchange.