Sarbanes-Oxley: The Long Compliance Journey

For senior executives and their boards in the oil and gas industry, improving the company’s performance and creating value is the main focus behind any new initiative, be it an acquisition or divestiture, a joint venture, re-engineering a supply chain, or a decision to outsource.

However, with the enactment of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, those same executives, their boards, and their audit committees are now required to focus a good deal of their labors on activities that, to some, may seem a distraction from their efforts to improve profits and drive value. Specifically, these activities involve complying with new regulations that address the effectiveness of internal controls over financial reporting.

Some leaders even believe that efforts to implement the controls required by the act’s Section 404 have diverted energy and resources from business-improvement activities without providing compensatory value. Nevertheless, companies are now at the beginning of a long “compliance journey.”

Going forward, organizations will need a dual focus: (1) sustain an ongoing assessment process for Sarbanes-Oxley compliance, and (2) balance risk and controls while identifying and pursuing performance-improvement opportunities to improve the business.

Ideally, efforts to comply with the act’s provisions will help the executive suite understand the nature of their company’s controls, processes, and systems; where they are located; and by whom they are performed - information that, for most companies, did not exist in one place before the Sarbanes-Oxley mandate.

These insights about the business, which can be derived from such detailed analyses of company controls and business processes, can lead to important business strategy changes. This knowledge provides leaders with a new means of considering and managing risk, improving the quality of their initiatives, and driving a return on the Sarbanes-Oxley investment.

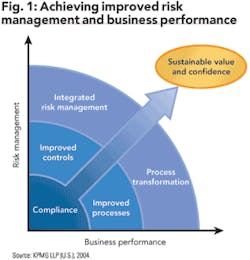

Most companies are in the initial compliance phase with the act’s Section 404, as represented in the lower left corner of the graph in Fig. 1. This series of compliance exercises can provide organizations with a foundation for executives to build further improvements to both their controls and their business processes - ultimately integrating risk management across the organization and transforming processes.

The positive result is that information on the organization’s controls portfolio - a collection of information about controls housed in one place - provides leaders with a new lens through which they can evaluate their businesses.

As a business lens, controls can become an important means of identifying new opportunities to manage risk, improve business performance, and add value, in both current and future initiatives with regard to growth. For example, companies evaluating the pros and cons of an acquisition should look long and hard at the target company’s system of financial controls before rendering a decision on whether or not to acquire or finalizing an asking price.

Understanding the scope, magnitude, and impact of controls across the organization requires a portfolio view. Using such an approach, an organization can assess its controls from different stakeholder perspectives - such as by business units, applications, geographies, risk concentrations, or management objectives. Each of these perspectives can be mapped in a similar fashion across four key control dimensions: automated versus manual and detective versus preventive, as depicted in Fig. 2.

The overarching goal in moving from manual/detective (backwards looking) controls to ones that are automated and preventive (forward looking) is to help ensure that controls occur at the appropriate places in the process. This helps to prevent, for instance, fraud or inefficiencies before they happen, as well as aids in the generation of relevant information, thereby enabling appropriate action.

An example would be to automate daily pipeline imbalance communications to management rather than wait for accounting procedures at month’s end to identify imbalance positions. Achieving this goal calls for an understanding of the process - as well as the nature and timing of the risks that arise during the process.

Daunting, however, is the sheer number of manual controls that need to be evaluated. Fig. 2 also suggests that organizations take a “bite-sized” approach by focusing on a particular business unit, then by moving to control applications, geographical considerations, risk considerations, and then ultimately to the management of the controls transformation.

Assessing the control dimensions is equally useful. Manual controls depend on people to evaluate the control, and thus carry a greater risk of nonperformance. When an urgent project arises, for example, staff normally responsible for a control activity, such as matching invoices to purchase orders and receiving reports, may be pulled off to perform other activities - thereby leaving control needs unmet. In addition, manual controls tend to drive costs upward and reduce operating effectiveness.

By contrast, automated controls can help reduce costs, better manage risk, and provide more predictive business insights. Automated controls often are embedded within enterprise resource planning (ERP) packages - such as balancing control activities, predefined data listings, data reasonableness tests, and logic tests - to prevent or detect unauthorized transactions.

An example of an automated control may be the establishment of predefined configuration requirements for field measurement data - such as maximum Btu values or minimum quality specifications coming into an ERP package. Such a strategy eliminates the need for manual identification of these potential data issues.

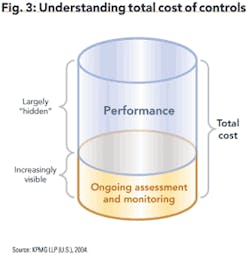

Of the potentially thousands of controls throughout an enterprise, much of their cost is related to performance - that is, the design, execution, and administration of controls.

In addition to incurring the performance cost of controls, organizations seeking to comply with Section 404 must now conduct an “ongoing assessment” of controls. Specifically, they must document internal controls over financial reporting, evaluate design and operational effectiveness, report on the assessment, and obtain a third-party audit of internal controls. Together, control performance and ongoing assessment activities make up the total cost of control, as depicted in Fig. 3.

Companies should be wary of focusing too much on the cost of deploying preventive controls, since large amounts of money are at risk or could be lost in the long run. For example, one organization may extend millions of dollars of credit to another based largely on an internal word-of-mouth recommendation (manual control).

It is only after the credit-line recipient is in default that the company discovers its control was detective and therefore could not prevent the tremendous risk. In this case, the investment benefits of a preventive control system would have far outweighed the money lost to a severe credit risk.

As oil and gas companies chart a course toward growth, they must include controls transformation as a key dimension in planning such change. Remediation of compliance gaps, new business initiatives, and other change events all present compliance imperatives as well as business improvement opportunities.

For a typical organization, the compliance/controls transformation journey - from a project-oriented state to a “new way of doing business” - will take many months or years. During each phase of the journey, the organization will seek to balance controls improvements with improved business performance.

Along the way, the question “How do we comply with Section 404 and other regulatory requirements?” becomes “How can we use controls as a news lens to support the integrity and value of information in a changing organization and dynamic marketplace?” OGFJ

The author

Steven Hill is KPMG LLP’s national principle-in-charge, Risk Advisory Services, and is based in Dallas. KPMG LLP is an audit, tax and advisory firm that is the US member firm of KPMG International. KPMG International’s member firms have nearly 100,000 professionals, including 6,800 partners, in 148 countries.