MANAGING PORTFOLIOS: Integrating upstream and downstream assets

David A. Wood, Consultant, Lincoln, England

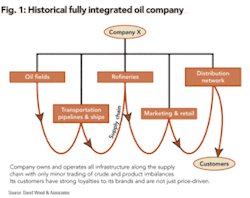

The traditional model of a fully integrated oil company is illustrated in Fig. 1. Interactions with other oil companies were limited (except in upstream joint ventures). The company produced its own product and supplied it to its own refineries and distributed highly differentiated product brands to loyal customers. Portfolio management at the corporate level was essentially two-dimensional with a limited number of strategic options to be taken into consideration.

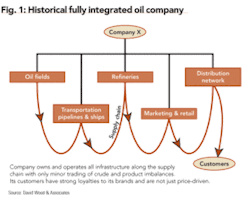

In contrast, fully de-integrated modern petroleum companies could not be structured or strategically positioned more differently (Fig. 2). In the extreme, each division operates as an independent company adopting business sector strategies and making day-to-day operational decisions that reflect the commercial realities of its markets.

In reality, most organizations employ corporate-wide portfolio management techniques to implement corporate strategies that coordinate the higher-level strategic decisions taken within the divisions.

Petroleum companies establish financial performance targets (i.e., earnings growth, return on average capital employed - ROACE - etc.) that straddle all their de-integrated divisions as well as setting and monitoring a range of strategically important and relevant financial and non-financial targets for each individual division.

Monitoring and benchmarking of performance is required at the corporate level and the division level. Most large organizations are obliged to report performance at each business segment level as well as consolidated results reflecting overall corporate performance.

Such segmentation and de-integration presents both performance advantages and challenges to portfolio management. The stand-alone business divisions are likely to perform better by having maximum control over their strategies and budgets and by being directly accountable for the performance of their own portfolio of assets.

On the other hand, the divisional fragmentation means that portfolio management and the integrated portfolio modeling process becomes more complex and has to be performed on at least two levels.

The highest level is for corporate decisions and corporate-wide strategic development. The second level is at the senior management of each business division. In the largest company the portfolio management and modeling process might have to cascade further down the organization into regional/international centers and business units.

The more levels involved, the more complex the portfolio management process becomes, and the more difficult it is to coordinate, communicate, and verify relevant information into and out of the highest level corporate portfolio management group in a timely manner.

Corporate-wide systems using web-based databases and drivers certainly help communication and standardization of information and analysis. However, successful portfolio management at multiple levels within a de-integrated organization requires more than sophisticated IT systems to work effectively.

Organizational alignment at the division and corporate level with the portfolio management process is essential. Close communications between portfolio group staff at the different levels and rotation of staff through division and corporate portfolio groups is required to establish a fully-integrated portfolio management process.

Flexibility needs to be built into the portfolio management process and the asset risk assessment and valuation process. Each division and business sector will have its own unique spectrum of operational risks and criteria required to assess those risks.

Some risks may be common to all divisions (e.g., political). Others may impact divisions differently (e.g., crude price influences upstream and downstream business in contrasting ways; price volatility can be an advantage to some trading groups but erode value in operational segments), and others may only exist for specific divisions (e.g., subsurface risks in the upstream).

It is important that risk assessment and performance monitoring criteria relevant for one business sector not be imposed upon others. The extra challenge for the corporate portfolio group is to integrate the lower level portfolio models and evaluation into a single model that can reflect performance and evaluate decision options at the corporate level.

Next month’s article is the final installment in this 10-part series. It will discuss the impact of corporate culture and perception on petroleum asset portfolio management. OGFJ

The author

David A. Wood [[email protected]] is an international exploration and production consultant specializing in the integration of technical and economic evaluation with management and acquisition strategy.

About this Series

This series of articles addresses fundamental issues of petroleum asset-portfolio management. The material is drawn from training courses in strategic portfolio management that the author has developed for the petroleum industry since 1998. The author writes in greater detail about these subjects in four executive reports available for purchase through the Online Research Center of Oil & Gas Journal Online. For a list of titles and descriptions, go to www.ogjonline.com, click “Online Research Center” on the left navigation bar, then click the link under “OGJ Executive Reports.”