Technology: The deciding factor in oil market success?

Part one: The physical and financial hurdles

PETER COOPERMAN, TRIPLE POINT TECHNOLOGY, WESTPORT, CT

Editor's Note: Oil markets are in a period of increasing uncertainty and traders' profits are being swallowed by shifting supply and demand dynamics. In the first of a two-part article series, Peter Cooperman of Triple Point Technology discusses the physical and financial risks involved in trading crude oil. In the second, he will examine the need for technology to manage and mitigate physical, financial and political risk as well as guide profitable trading decisions.

Introduction

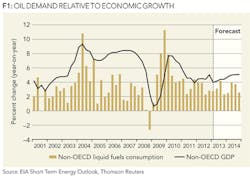

Economists and anthropologists often cite crude oil consumption levels as a leading indicator of a nation's financial status. Crude consumption is a reliable reference point because the fuels and feed stocks derived from crude are crucial in manufacturing and as fuel for construction equipment used to expand infrastructure necessary to support the growth of a nation. Higher demand can also reflect a society's appetite for more luxurious items beyond basic necessities. The introduction of more refined fuels, plastic-based products, and asphalt (in the form of paved roads) can also signal growth. As shown in Figure 1, countries tend to experience higher demand for oil during periods of growth. Crude is preferred as an indicator over natural gas or coal because it's the most consistent in its use, and it's the most flexible non-renewable energy commodity when it comes to transport. Crude can be sent by pipeline, truck, rail, or vessel with minimal preparation. This makes it possible for supply from one side of the globe to meet demand on the other.

This versatility ensures that physical crude oil markets will remain active, with producers and consumers working to determine the optimal level of crude needed to run their businesses. The disparity between perceived and actual need contributes to the ongoing volatility in oil markets. Traders are eager to capitalize on market swings and have made crude oil the most widely traded commodity in the world. Market participants that are able to properly forecast price movements can profit by trading physical and/or financial contracts. This is easier said than done because trading crude successfully is no small task. There are many different types of crude oil that are traded and a seemingly infinite list of factors that affect the price of each barrel. To succeed, participants must monitor market sentiment and react quickly to events that may affect oil production, refining, and transport.

Market participants face a great deal of uncertainty. Oil is traded on a global scale, and participants must analyze vast amounts of data and keep abreast of market related news from all over the world to assess market risk. Volatility is greater than ever as new technology, security concerns (theft/piracy), and new methods of setting prices reshape market dynamics. Traders must also cope with the effects of unforeseen production, refining, and transportation issues, while remaining vigilant in gauging geopolitical climate changes. The slightest miscalculation in refining capacity, underestimating the tact of a determined oil thief or misjudging the impact of a political event, can eliminate any opportunity for success.

Physical commodity management

News of crude oil discoveries has re-shaped economic outlooks and has become a leading topic of conversation for industry insiders and outsiders alike. Drill operators have honed hydraulic fracturing techniques and gained a newfound ability to locate proven reserves. North America, in particular, has found itself at the forefront of the tight sands and shale oil revolution. A recent report released by the US Energy Information Administration cited a 15% increase of proved crude oil reserves from 2008 to 2011 in the United States. Reports of similar findings, and the introduction of more efficient recovery methods, have reverberated around the world. At least one OPEC member has expressed his concern that the heavyweight organization is losing some of its ability to manipulate markets because it can no longer control levels of supply. As additional areas seek to apply fracking to their own exploration efforts, the markets must brace itself for continued shifts and increasing uncertainty.

The impact of new crude oil discoveries is still unraveling and has created a need to update existing transportation infrastructure to support supply growth. Many areas must undergo massive expansion to facilitate moving crude oil reserves economically. A large investment is often necessary because tight sands and shale oil are generally located in remote areas, with no cost effective means of transportation. To unlock the value of these new discoveries, producers must find ways of moving large amounts of oil to refineries, most of which are strategically placed at hubs to ease entry of end products to market. The Bakken Shale play in the Mid-West United States exemplifies this trend. Until recently, the area was primarily concerned with consumption so that infrastructure supported bringing in refined energy products. Successful exploration changed that, and it is now a leading producer of oil and natural gas. New pipelines and plans for them have been laid, and existing pipelines have been retrofitted to reverse their flow, so that recovered crude can make it from major hubs in the area to large refineries in the Gulf of Mexico. While projects wait for approval and completion, market participants must rely heavily on truck and rail to move oil over land and vessel by sea. This transformation is not unique to the US. Similar changes are also being proposed in Canada, and elsewhere, to make reserves more accessible. On a global scale, plans are underway to reverse the purpose of existing import and export terminals as supply lines are redrawn.

When dealing with physical contracts, participants must manage the complex crude oil supply chain to maximize profitability. They must determine preferred routes, with the lowest financial cost weighed against perceived transport risks while accounting for time constraints. Commodity contracts are extremely complex, and the penalty for missing a quality mark or delivery date tends to be severe. Midstream and downstream players from all over the world face challenges around managing crude oil movements throughout the supply chain. Crude oil purchases must be balanced against end product delivery commitments, and complexity grows exponentially with each additional contract. Oil companies can no longer rely on manual processes to assess risk as the scale and complexity of oil markets continue to increase.

Recent headlines provide a clear indication that the midstream and downstream oil industries are proving to be very difficult. Bloomberg News has reported that refiners in Europe will shut 10% of their plants this decade due to tight margins, and falling demand. At the same time, at least one major corporation has announced that it is leaving the downstream business altogether due to falling margins and accumulated losses.

Financial commodity management

The road doesn't get easier for participants that trade oil on a strictly financial basis. The ability of a trader to accurately monitor risk, and react ahead of the other market participants defines his success. Participants rely on a combination of historic data, risk analysis and intuition to guide them, but today's market requires a more advanced approach. Capturing relevant information that can affect the supply and demand for a given type of crude oil is extremely difficult. Oil markets operate on a global scale, and manual risk calculations and legacy spreadsheets can no longer support successful trading.

Part of the challenge of trading oil is brought about by the number of varieties that exist. More than 280 types are being traded today. Several blends are used as reference points when comparing different crude oil types. These benchmarks were established to simplify valuation among grades but market volatility along with the shifting supply and changing of infrastructure have lessened their relevance. The faults of established pricing methods have been exposed recently. Platts has altered several of its valuations and requirements as a result of changing market conditions.

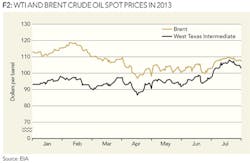

Newfound supply and improved infrastructure has also changed the dynamic of the two most traded benchmarks in the world. The spread between them, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) and Brent Premium, has long been a favorite play of speculators. Over the past five years it has fluctuated from a peak at $23 per barrel to settling near parity at approximately $109 per barrel on July 19, 2013. Over-simplified analysis has led many traders to overlook factors beyond the seemingly abundant supply of WTI.

The gap between WTI and Brent shrank in 2013 (as shown in Figure 2) and has decreased due to a combination of factors. Political stability, timelier infrastructure improvements, and greater refining efficiency have all played a role. Technology would have enabled traders to foresee this change in market dynamic. A longer-term review of the barrel price of WTI exemplifies crude's extreme volatility. Over the past five years, its average spot price has fluctuated from $61.95 in 2008 to over $95 in 2012. Price fluctuations like those observed in WTI illustrate why properly managing risk, and the ability to react quickly to market change, is so vital to the success of a trader.

Physical and financial challenges in the market represent significant pitfalls that must be dodged by those looking to make profitable trading decisions with crude oil. They cannot be ignored, and as the trading environment grows more volatile and complex, they cannot be managed using paper-based or spreadsheet solutions. The second part of this series will explore the political risks involved with the physical and financial factors currently affecting market participants. It will also assess the role of dedicated commodity risk management software during these challenging times.

About the author

Peter Cooperman of Triple Point Technology, a provider of on-premise and in-cloud commodity management, has always held an interest in commodities markets. He works to publicize the benefits of leveraging advanced analytics software to manage risk and promote better decision making. Prior to working for Triple Point, he headed solutions marketing and software product management at a global technology provider. He graduated from Binghamton University with a bachelor's degree in economics.