Part 4: Producer and consumer price indices reveal contrasting fortunes - CONTROL & INFLUENCES ON WORLD OIL PRICE

David Wood, David Wood & Associates, Lincoln, UK

Saeid Mokhatab, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyo.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This 5-part series of articles explores how different sectors of the oil supply chain are generically controlled by different international groups and how these controlling factions influence prices and fuel geopolitical tensions. Part 4 reviews the trends of key price indices that imply that consuming nations have extracted more value from petroleum products than they have paid for their crude oil feedstocks up until the last year or so. A brief review of models used to predict short-term oil prices suggests that using supply, demand, and inventory volumetric data in isolation is unlikely to provide satisfactory forecasts.

Access to cheap supplies of energy, especially crude oil, has historically underpinned much of the economic growth achieved since World War II by the OECD consuming nations, no more so than the United States.

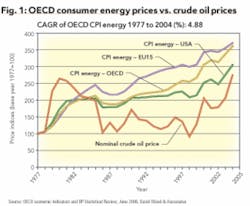

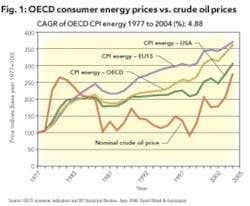

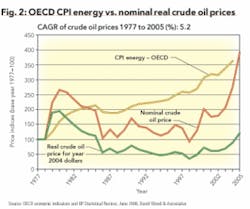

Actual costs of production of goods and services (net taxes) thus remained low in OECD countries - with significant impacts on overall international trade flows in many manufacturing industries. Indeed, the crude oil price index has remained lower than the consumer price index (CPI) for most of the past two decades (Figures 1 and 2), which emphasizes the extent to which crude oil has remained a cheap primary energy source until quite recently.

Security of long-term oil supplies has been a concern to OECD and IOCs since the 1970s due to the vast majority of proven oil reserves (about 75%) being located mainly out of reach and under OPEC control. Low reserves/production ratios (R/P) for most OECD countries and the IOCs have persuaded them to invest heavily in sometimes expensive to develop and produce non-OPEC supplies.

Developing such high lifting cost oil, for reasons of geopolitics, in preference to low lifting cost OPEC oil resulted in marginal project economics during periods of modest oil prices, for example 1986 to 1999. Such developments contributed to the perceived over-supply that leads to a suppression of the oil price. As the marginal cost of supply of remotely located non-OPEC oil continues to rise, it is reasonable to expect that OPEC’s low-cost oil will gain in market share.

However, from an OECD perspective, there is the perception and concern of short-term and long-term chronic shortages of oil supply manipulated by OPEC and Russia, outside the control of the IOC’s downstream infrastructure. This exists alongside a broader global picture (ignoring geopolitics) of apparent abundant supplies from development of remaining proven reserves of low-cost oil.

This perception has enabled OECD governments through taxation and IOCs through control of the refining capacity, downstream marketing and distribution infrastructure, to shift the burden and cost of such risks onto their petroleum product consumers. At the same time the non-OECD producing nations continue to remain dependent in the short-term on access to the predominantly IOC-controlled downstream networks to benefit from high crude oil prices.

The oil price indices of Figures 1 and 2 show little growth between 1985 and 1999, with all indices growing rapidly since 1999. Crucially, the OECD CPIs in 2004 remain higher than the crude oil index. Figure 2 however suggests that a crossover has occurred in 2005 - nominal oil price index higher than OECD CPI (energy) for the first time since 1983.

This implies, in general terms, that OECD governments and IOCs have extracted more value from petroleum products than they have paid for the crude oil feedstocks up until 2005. Note the real crude oil price index (in 2004 US dollars) lies below 100 from 1986 to 2004 and only climbs above 100 in 2005.

Values of this index below 100 indicate that crude oil price has failed to keep pace with inflation, reinforcing the premise that crude oil has remained undervalued when compared with consumer energy prices in OECD. This clearly suggests that OECD downstream is extracting more value from oil downstream than the producing nations are upstream.

When crude oil producing nations historically realized the gap between the OECD CPI and the oil price index was widening, they devised strategies in the 1960s and 1970s to redress the balance. However, except for a few short-lived periods (e.g. late 1970s/early 1980s - Figures 1 and 2), the oil price index had remained below the OECD CPI during the previous 50 years.

As a result, cheap oil and large domestic markets in most of the OECD consuming countries has helped them to retain a comparative advantage at the level of international trade in petroleum products and energy intensive manufactured goods. They emerged as the lowest-cost producers of goods and services in greatest demand, and easily maintained a dominant position as exporters of such goods and services to the non-OECD producing nations.

On the other hand, apart from efficiently exploiting their highly specialized and advantaged position in the export of crude oil, the major oil-producing nations have for the most part failed to make great inroads into broader international trade or the downstream petroleum sector and remained essentially petro-economies.

A case can be made that the producing nations have been disadvantaged because crude oil prices have been maintained at low level by the OECD control of the downstream industry. An equally strong case can be made, however, to the effect that even at modest crude oil prices the major producing nations have earned trillions of dollars of revenue over the past 40 years, but in most cases have failed to invest it wisely in economic development internationally along the crude oil supply chain and in diversification to other industrial sectors.

Malaysia is perhaps one example of what could be achieved through such strategic international reinvestment of petro-dollars begun in the 1970s.

Price modeling and forecasts

Oil price instability, and hence uncertainty, pose significant challenges to oil market participants in various decision-making requirements. An accurate forecast of the expected future price of oil will always be of significant benefit to such participants in making informed decisions.

The range of forecasting methods available offer varying accuracy, scope, time-horizon, and cost, and can be categorized as either - quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative methods rely principally on human experience, judgment and intuition (including pure guesswork). Quantitative techniques attempt to be systematic, verifiable, and use formal statistical models, but require good data to be effective.

It is important to recognize that oil price forecasts that become widely reported and considered as well founded can lead to self-fulfilling or self-defeating prophecies.

Time series quantitative models breakdown an historical time trend into seasonal, cyclical, and error components and predict the future assuming history will repeat itself. For example, the Box and Jenkins “autoregressive integrated moving average” (ARIMA) models. These are criticized by some for their “black box” approach that makes no attempt to discover the factors affecting the price series being modeled and therefore being unable to provide an economic understanding of the underlying causes of the forecast trend. The technique uses statistical analysis to establish an appropriate model and then test the fit of the model against that time series before then extrapolating it to the future.

On the other hand causal, econometric models develop a cause-and-effect relationship in the form of a numerical equation(s) linking several input variables to generate the desired output of future oil price. Many forecasting models for oil traders focus on price volatility and long-term rather than short-term oil price forecasts. Some simplistic models express oil prices in terms of interactions between oil supply and demand.

Petroleum inventory level movements (strategic and commercial OECD oil stocks) are used as an indicator of balance or imbalance between petroleum output and demand and interpreted as a key driver of short-term crude oil price behavior. Monthly OECD oil inventory data are available from US Energy Information Administration (EIA), and it is defined as the total of industry and government-controlled stocks of both crude and petroleum refined products.

Such data show periodic cyclical trends over the past decade with deficits and surpluses and seasonal trends, commonly stock building in the northern hemisphere summer months. The desired inventory (market equilibrium) level at any given time is calculated using regression analysis by taking away the time trend and seasonality. A comparison with actual versus “desired/equilibrium” inventory levels is then used to forecast whether oil prices should be expected to rise or fall.

Analysts have compared the performance of the ARIMA model, a simple econometric model, and guesswork models to evaluate Brent dated oil price movements. Using Brent dated price data and OECD inventory from January 1992 to December 2004 to build the models, those models were then compared to (used to predict 1 month ahead) the same price and inventory variables from January to September 2005.

The ARIMA model outperformed the econometric model (which was also outperformed by guesswork). It does not surprise these authors, based on our foregoing discussion in this and previous parts of this series of articles that even 1-month ahead oil prices cannot be effectively predicted using simplistic models trying to rationalize price movements in the simplistic terms of OECD oil inventory alone.

Many other complex and difficult-to-predict factors clearly influence oil price: geopolitical events, market perception of adverse reactions to global reserves data, IOC performance, nationalizations, global conflict, weather-related extremes (fear factors), subjective positive sentiment to broader economic performance, and not least the subject of this article - excessive control exerted along the oil supply chain by distinct oligopolies: OPEC and Russia upstream; IOCs downstream.

The performance of various oil price models can never be expected to provide sustainable accuracy. Their performance also often varies with the forecasting horizon, making it risky to rely on one type of forecasting model, bearing in mind the multiple complex impacts on the oil market (beyond simple supply, demand, and inventory volumes) that the models tend to ignore.

About The Authors

David Wood [[email protected]] is an international energy consultant specializing in the integration of technical, economic, risk, and strategic information to aid portfolio evaluation and management decisions. He holds a PhD from Imperial College, London. He is based in Lincoln, UK, but operates worldwide.

Saeid Mokhatab [[email protected]] is an advisor of natural gas engineering research projects in the Chemical and Petroleum Engineering Department of the University of Wyoming. He has published more than 50 academic and industrial papers, reports, and books. In addition to his technical interests, he has written extensively in wide-circulation media on a broad range of issues associated with LNG, LNG economics, and geopolitical issues.