Part 2: Expanding future roles for Canada and Mexico - The North American gas economy

EDITOR’S NOTE: This 2-part series of articles examines the production, transportation, and marketing of natural gas in the economy of North America, how it is continuing to evolve, and important trends that will affect demand and prices. Part 2 takes a close look at the expanded future roles of Canada and Mexico in the energy equation.

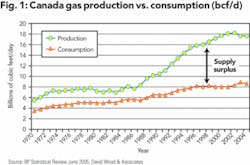

Canada supplies about 16% of natural gas consumed in the US. During the period 2000 through 2003, this represented 57-60% of all the natural gas produced in Canada. Clearly Canada is not producing gas for itself and exporting what it cannot consume. Rather it is producing gas for export while domestic consumption is satisfied incidentally (Figure 1).

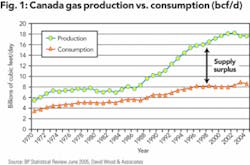

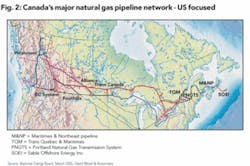

Much of Canada’s pipeline infrastructure was tied into the US markets in the 1980s and also served residential and commercial markets in the larger centers of Alberta as well as southern Ontario and Quebec. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the considerable degree to which Canadian natural gas infrastructure and marketing arrangements are linked to the US gas grid.

The Maritimes and Northeast pipeline, one of the newest transporting gas from Canada to the US and more than 400 km in length, was financed in part by tax subsidies from the federal and provincial governments involved. It was designed purely with the US market in mind with few plans to develop any of the Sable Offshore Energy Project’s gas for a potential residential market of about 1.5 million people in central and northern Nova Scotia and southern New Brunswick.

There was only a very long-term notion of supplying a tiny industrial market in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia and Saint John, New Brunswick. NRCan (“Natural Resources Canada”), the Canadian federal department responsible, explain clearly that the objectives in expanding pipeline and terminal infrastructure are to benefit from transiting gas deliveries into the US gas market.

Considerable progress has occurred in recent years to connect Canadian natural gas supplies to US consumers. The Northern Border Pipeline, an extension of the Nova Pipeline, came onstream in late 1999 and connects to Chicago through the upper Midwest. A further extension to Indiana entered service in 2001. The Maritimes and Northeast Pipeline came onstream in January 2000, running from Sable Island to New England, with further extensions into the Boston area to be completed during 2003. The pipeline has a capacity of 400 MMcf/d.

The $2.5 billion Alliance Pipeline, at 1,875 miles, is the longest pipeline ever built in North America, and is designed to carry about 1.3 bcf/d of gas from western Canada (Fort St. John, British Columbia) to the Chicago area. The pipeline began commercial service on December 1, 2000. The US utility Pacific Gas & Electric imports natural gas from British Columbia via the Alliance pipeline.

Another possibility for future US natural gas supplies lies in northern Canada, which contains around one third of that country’s recoverable gas reserves. The Mackenzie Valley pipeline, for instance, could carry as much as 1.2 bcf/d of gas from Canada’s far north to southern Canada and the United States, possibly beginning in 2010 (assuming satisfactory completion of a regulatory and environmental review; currently, the project appears stalled).

However, Canada is consuming increasing volumes of gas itself for such activities as oil sands extraction and processing. Accordingly, Canada may export less natural gas to the United States than is now expected. A competing pipeline would transport natural gas from Alaska’s North Slope to the lower 48 states, with possible capacity as high as 4 to 5 bcf/d, potentially beginning sometime around 2012.

Canada as a source of supply of natural gas to the US will become increasingly problematic to the extent that synthetic crude oil exports from Canada to US have become a larger part of projected North American “energy security” and security of supply. This follows from the fact that the key to expanding production to meet such enhanced demand for synthetic crude will involve diverting more and more of Alberta’s natural gas reserves to processing tar sand bitumen, the raw material source of synthetic crude.

Canada’s proven natural gas reserves, 56.1 tcf as of January 2005, only rank 19th in the world. These reserves have decreased by 13% since 1996, and at current rates, production will completely deplete proven reserves in 8.6 years (in the absence of reserves replacement investment activities).

What could cause such a drastic depletion? The oil sands industry is heavily reliant upon water and natural gas, which is necessary in both the extraction of bitumen from oil sands and the upgrading of bitumen to synthetic oil.

The vulnerability of existing marketing mechanisms of the entire “downstream” sector of the North American oil and gas industries to increases in natural gas prices, or sharp reductions in natural gas supply, would be extremely unevenly distributed, with the oil sands industry likely to experience the most critical repercussions.

One interpolation that is consistent with these facts is that, short of new discoveries of natural gas in Canada, the main value of Canadian territory to the US gas market in coming years will be for transiting LNG from its ports and pipelines to US markets.

Adding further credibility to that scenario is a published projection by Natural Resources Canada in 2004 of LNG’s share of the US gas market rising 5 times over the next 15 years to 2020. The profitability of such arrangements is clearly premised on utilizing new / future supplies of gas increasingly and mainly for electrical power generation and related industrial use, and less and less for residential or other commercial uses (e.g., as an alternative to gasoline).

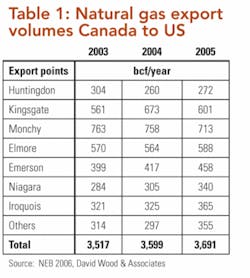

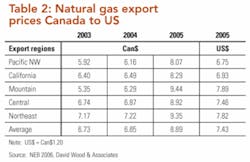

In order to meet expanded US market demand for natural gas by supplying LNG, an increasing integration of US and Canadian gas infrastructure is developing. Tables 1 and 2 compare annual volumes and average annual prices of natural gas exported from Canada to United States from 2003 to 2005. More than 3.5 tcf of gas exports per year and a trend of rising export natural gas prices is good news for the Canadian natural gas exporting companies, but less good news for Canadian natural gas consumers both in terms of price and long-term availability of domestic natural gas supply.

Canada’s “deregulated free market” has depended upon supplying the US’s thirst for natural gas in order to develop and survive. It may be a free / deregulated market, but it cannot be considered as independent (“independent” from the US market that is) in many respects, particularly with respect to prices.

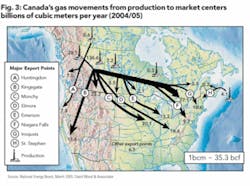

The pace of future development of much of northern Canada’s undeveloped natural gas resources (Figure 4) will undoubtedly continue to be driven, to a large extent, by issues of natural gas demand growth, price and domestic production decline in the lower 48 states of the US.

Recent developments impacting Mexico’s gas market

Mexico has proved natural gas reserves estimated (as of January 2005) at about 15-20 trillion cubic feet (tcf). In 2005 Mexico was the 15th largest producer of natural gas (accounting for about 1.6% of the world’s total annual natural gas production), but its growing demand for this resource has made it a net natural gas importer. Imported gas has in recent years come by pipeline from the US, but high prices and tight domestic US demand have led to Mexico seeking its own LNG import capacity.

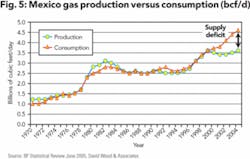

Mexico is now the eleventh-largest consumer of natural gas (accounting for about 1.9% of the world’s total natural gas consumption). Natural gas consumption in Mexico is now more than 90% greater than it was a decade ago. Demand is climbing so rapidly due to growing reliance on gas-fired power generation, which will account for nearly half of all natural gas consumed in Mexico within the next decade. In Mexico, future natural gas consumption is expected to far outstrip production.

Mexico’s demand for natural gas has been projected by the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) in their July 2005 Energy Outlook to grow at an average annual rate of 3.0% per annum to 2025. In contrast, Mexico’s natural gas production is expected by EIA to grow at a rate of only 1.7% annually. Most of the growth in consumption is expected to fuel electricity generation.

Although consumption in the residential and commercial sectors combined accounted for less than 3% of the country’s total natural gas use in 2002, pipeline infrastructure to serve residential and commercial users is expected to continue growing, allowing Mexico’s natural gas consumption to increase tenfold from 2002 to 2025.

Mexico’s dependence on natural gas imports, like that of the United States, is projected to increase (Figure 5). In the EIA’s July 2005 energy outlook reference case, natural gas imports are expected to grow from 13% of Mexico’s total natural gas consumption in 2002 to 37% in 2025.

The Mexican government is attempting to attract foreign capital to help in developing the country’s own abundant resources and supporting production increases, but to date little increase has been seen. State control of the petroleum sector through Pemex is inhibiting its ability to explore and develop deepwater gas resources in the Gulf of Mexico due to limited access to capital and technology.

LNG is expected to be the biggest contributor to Mexico’s additional natural gas supply in the near term. In addition to the Costa Azul import facility in Baja California, Mexico, that is under construction and will serve both Mexican and US markets, another LNG facility is under construction at Altamira on Mexico’s Gulf Coast. In addition, several LNG receiving facilities projects are currently under consideration distributed along the length of Mexico’s Pacific Coast, primarily to serve the Mexican market.

Several major companies have sanctioned investments in Mexico in recent years to achieve access to the lucrative Californian gas market. For example, Repsol YPF has taken positions in Mexico and in Peru along a new LNG supply chain targeting entry to the North American Pacific coast, whereas Shell is looking to bring LNG from its Sakhalin II project (eastern Russia) on the other side of the Pacific Ocean.

About the authors

David Wood [[email protected]] is an international energy consultant specializing in the integration of technical, economic, risk, and strategic information to aid portfolio evaluation and management decisions. He holds a PhD from Imperial College, London. Research and training concerning a wide range of energy related topics, including project contracts, economics, gas / LNG / GTL, portfolio and risk analysis are key parts of his work. He is based in Lincoln, UK, but operates worldwide.

Saeid Mokhatab [[email protected]] is an advisor of natural gas engineering research projects in the Chemical and Petroleum Engineering Department of the University of Wyoming. He specializes in the design and operations of natural gas transmission pipelines and processing plants. He has participated in several international projects related to his areas of specialization, and has published more than 50 academic and industrial oriented papers, reports, and books. He has written extensively in wide circulation media in a broad range of issues associated with LNG, LNG economics and geopolitical issues.