History in the making: the evolution of the 144a market

Mikaila Adams Associate Editor, OGFJ

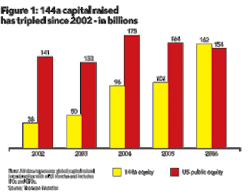

The private equity market has grown substantially in the last five years. NASDAQ estimates that the amount of equity and debt capital raised using Rule 144a has grown three–fold since 2002 and exceeded $1 trillion in 2006 for the first time. In the first half of 2007, global equity and debt capital raised in conjunction with the 144a market was almost $1 trillion, a 43% increase over the first half of 2006.

Numerous systems and platforms have set up shop in anticipation of the rush. “This is historical,” said Larry Allen, managing member of New York Private Placement Exchange (NYPPEX), which focuses on the resale of 144a dealflow. “Private companies never had these alternatives to think about before.”

The beginning

The Securities and Exchange Commission adopted Rule 144a in the early 1990s as an efficient, low–cost way to access US capital and institutional investors. It allows for the immediate resale of private placement securities among qualified institutional buyers (institutions that manage at least $100M in securities and are referred to as QIBs) without requiring public registration.

This provides efficient access to US capital at a lower cost than traditional public US offerings. Companies from all over the world have used Rule 144a to raise capital and increase their company’s profile with US institutional investors including banks, savings and loan institutions, insurance companies, investment companies, or employee benefits plans.

To retain their private status, companies may have no more than 499 qualified institutional investors.

Until recently, only few systems were in place for 144a transactions. Securities sold had to be physically delivered, usually through a transfer agent. Ticket mechanisms were used to count shareholders. You only put out 499 tickets, so unless you had a ticket in your hand you couldn’t buy the stock.

Benefits

Most agree that the two biggest benefits to the private equity market are speed to market and the ability to limit disclosure.

This was true when the market began in the early ‘90s. Now, with the added regulations of Sarbanes–Oxley, the market is even more appealing. At an August 23rd presentation at Rice University in Houston, Michael Oxley, one half of the notorious Sarbanes–Oxley duo and now vice chairman at NASDAQ, mentioned that those involved in the private placement dealings are excluded from the SOX regulations.

In a somewhat ironic twist he said they “can take care of themselves and have a long history of doing so.” He says the bottom line is that there is “less cost, less regulation, less paperwork” and that the companies will, in turn, “move to the public market when the time is right.”

“Some will want to access the markets quickly; some will want to avoid disclosure about certain assets of their business. Those are the two big drivers: speed to market and ability to limit disclosure,” said David Ballard, managing director of equity capital markets at Merrill Lynch in New York.

NASDAQ executive vice president John Jacobs also agrees. The 144a market has “clearly become a very big pool for energy companies to access the capital markets because it’s fast and cheap,” he said.

The transition

While 144a transactions have been around for awhile, the standard drawback has always been lack of price data and liquidity. That is until recently, when people started to suggest ways to increase liquidity in the market.

Goldman Sachs started the trend with GSTrUE. The company opted to act as the ‘counter’ to make the market more liquid. OPUS–5 is very similar except that instead of any one bank being the counter, The Bank of New York Mellon is that counter.

Two things are changing in the market. Not only are people no longer physically running tickets all over lower Manhattan, but private company attitudes are changing.

While private companies still remain relatively tight–lipped about their financial information, you can expect to hear more in the coming months about private companies raising capital through the private market.

“Up until Goldman announced its system, partnerships have instructed us to do this as quietly as possible…no tombstones and so forth,” said Allen. “Now business is changing. Private companies are going to be more inclined to have their securities traded and as long as they’re not dealing with SOX or having to register with the SEC…that’s a happy medium for them,” he continued.

Effect on IPO market

Many companies say the cost of going public far exceeds the benefits. As Figure 1 indicates, the amount of capital raised last year through the 144a market – $162 billion – was bigger than all the IPOs and secondary offerings on NASDAQ, the NYSE, and AMEX combined.

In 2006, seven of the top 10 IPOs raised capital in the 144a space. Many see this as proof the 144a market is being used as a stepping stone to the public market.

Goldman Sachs’ Ed Canaday says that some companies may view the 144a market as a stock valuation tool on the road toward public listing. “With private placement capital in hand, companies have the time and flexibility to grow the business, evaluate options, gain experience, and develop more accurate pricing, all of which can help lead to a more effective IPO.”

“While we see the activity in the 144A equity market increasing, we do not see our traditional underwriting and trading businesses diminished in a material way by Rule 144a equity offerings. We believe that companies will raise money in both the public and private markets depending on their specific situation,” he continued.

NASDAQ’s Jacobs agrees. “As you get down the road you’ll see this as a regular process for raising capital,” he said. He went on to say that he thinks “eight out of 10 IPOs will go private to PORTAL to NASDAQ.”

NYPPEX’s Allen sees things differently. “It [private market investing] is going to compete with IPOs because the amount of capital that Goldman, etc. had available has reached a critical mass point.” He thinks that private companies are now comfortable that their securities can trade fairly consistently and get a fair price.

Allen explained that “this private market, particularly the global private market,” has reached a point doing secondary private transactions where all the players involved feel that “this is a real market now and we can depend on it.”

Couple this with the recent trend of companies listing outside the US, and you have something to ponder.

The contenders

There are a number of places now offering similar services intended to improve the efficiency and transparency of the private placement market – thereby encouraging capital formation. While for the most part the services offered are similar, there are a few variables that investors and companies alike should consider.

As NASDAQ’s Jacobs told OGFJ, proprietary systems created by investment banks such as Goldman Sachs and Merrill Lynch will not attract the business of the competing banks’ customers. NASDAQ sees itself as the “neutral platform” in that regard.

At the same time, NASDAQ’s PORTAL is currently without a tracking mechanism. Some see this as the PORTAL’s ‘Achilles’ heel.’ Ron Sommer, Bank of New York Mellon Corp. said, “PORTAL is up and running and it works, the issue is that it only settles through DTC (Depository Trust Company) currently. The problem is that if you settle any transactions through DTC you can’t track it. You can’t know that you’ll have fewer than 500 holders.”

However, NASDAQ is currently working with Bank of New York (the same bank used by OPUS–5) to incorporate an industry–wide shareholder tracking solution into its system.

Jacobs sees the issue of shareholder tracking differently. “OPUS–5, GSTrUE, and Bear Stearns don’t do the trading that we do. They do shareholder tracking for companies that need to preserve their corporate structure. We’re approaching tracking differently. From our perspective three out of 4,738 deals needed it so it wasn’t our leading battle.”

He said that only three companies in the last 21 months have asked for shareholder tracking because most want to go institutional.

“I understand why the firms did it first because they’re protecting their investment banking. It doesn’t provide a good trading market, but that’s not the point. They are single purpose responsibilities,” he continued.

Goldman Sachs

As mentioned above, Goldman Sachs’s GSTrUE (Tradable Unregistered Equity) was the first to offer this new type of 144a securities trading platform. GSTrUE is a multibroker platform, meaning that GS and other brokers can list and trade on GSTrUE.

The company developed the system over the course of 2006, and the company’s first transaction came in May 2007 with the $880 million offering of 15% of Oaktree Capital Management. Later, in August, Apollo Management Group listed on GSTrUE with three underwriters and market makers: Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan, and Credit Suisse. The company attests that it is the only currently operating 144a platform with two successful offerings under its belt.

Ed Canady of Goldman Sachs said, “An important aspect of GSTrUE is the role of the independent transfer agent, AST, which provides shareholder tracking/monitoring to ensure that the total number of shareholders does not exceed 499.”

The company recently announced that the patent filed in May to protect the IP of the GSTrUE technology will be opened for peer review under the US Patent Office’s new process.

OPUS–5

The Open Platform for Unregistered Securities (OPUS–5) began operations in mid–September. The group originally consisted of Citi, Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, and The Bank of New York Mellon (acting as an independent administrator). Later that month, Bank of America, Credit Suisse, and UBS joined the group.

OPUS–5 provides trade reservation, shareholder tracking, and transfer management for privately offered equity securities. The platform supports and enables an open platform with multiple market makers. Like the other entities, it is designed to provide broad liquidity to the US private placement market and facilitate greater access to capital for issuers in the 144A equities market.

Bank of New York Mellon’s Sommer said that “investment banking members of OPUS–5 are much better sources of information on the overall 144A securities market.”

He says that OPUS–5 is working with US registered companies who are concerned with keeping shareholders under 500. He believes the companies currently doing business with PORTAL are mostly foreign and that, while foreign companies aren’t supposed to have more than 299 holders, there isn’t a big push for the SEC to get involved. “The chances of the SEC being concerned with the foreign companies are a lot lower than it being concerned with US companies,” he said.

NASDAQ PORTAL

Unlike GSTrUE or other systems only willing to trade that particular firm’s clients’ 144a units, PORTAL is open to trade any eligible 144a units.

The NASDAQ Stock Market Inc.’s centralized trading and negotiation system for 144A securities, PORTAL, began operations August 15. The fully automated web–based platform, an outgrowth of NASDAQ’s 17–year old PORTAL system, is the first centralized electronic system for displaying and accessing trading interest in 144a issues.

The PORTAL Market has this year alone designated more than 1,700 144a equity and debt securities as PORTAL securities, compared to nearly 2,700 in all of 2006.

NASDAQ’s Jacobs explained the differences in the systems. “For a trading platform, you have to have some link between a client and a market maker. In the OTC world that’s a phone call, in program trading it’s through a computer. That’s the front end. Technically GSTrUE is that communication over its stock trading platform. It’s a way to electronically communicate with investors about these restricted securities. It provides the ability to trade other securities through that same computer system. You could have traded it just as easily over the phone, but you’re doing it electronically and they branded it.”

It is also his opinion that OPUS–5 came into being, not because PORTAL came up, but because GSTrUE came up. “They’re competing for the investment banking business,” he explained.

He went on to say that “GSTrUE, OPUS–5, and Bear Stearns compete with one another, but they don’t compete with PORTAL. In the last 21 months from Jan. 1, 2006 through Sept. 30, 2007, the firms of OPUS–5 and Goldman Sachs and the ones on The Street have brought PORTAL 4,738 deals. Most of those are debt so they’re not in the PORTAL trading systems yet. There are three deals that have not come to us.” Two went to Goldman Sachs and one went to Bear Stearns.

When NASDAQ completes the installation of its shareholder tracking mechanism, “the others would have to extend their role because then they would be in competition with PORTAL,” said Jacobs.

NYPPEX

Since 1999, NYPPEX has quietly traded unregistered securities of private companies as well as interests in private partnerships. The company is a registered broker–dealer that provides access to over $10 billion in global secondary private market liquidity through its 76 institutional members. US and non–US companies may now list their unregistered securities at NYPPEX through an Initial Private Listing (IPL).

NYPPEX’s Allen also noted competitive links between the various systems. “With Goldman’s announcement of its TrUE system, NASDAQ got back in the game and reworked the PORTAL business.”

Allen also believes that shareholder tracking is important. As part of the set–up process, NYPPEX asks the issuer to appoint a law firm or stock transfer agent to act as a registrar for shareholder tracking. The company has access to the records and, as part of its technology, tracks the number of shareholders for each company being traded.

For the 2Q2007, on average, NYPPEX price executions for unregistered equity securities of private companies averaged 105.63% of the seller’s stated fair values. Therefore, for a sample week in April 2007, NYPPEX traded securities of 14 private companies for a notional principal amount of $57 million at an average price of a little over 105% of the seller’s stated fair value.

“This is important as it is telling CEOs of private companies, including energy companies, that their company’s securities can be traded at prices that imply a very attractive valuation for their companies,” explained Allen. “This can support bank lines of credit and future capital raises,” he continued.

Conclusion

Deep–pocketed institutional investors are spending billions in the private equity market. Last year, not only did the market overtake the combined public stock exchanges in total capital raised, but one of the exchanges, NASDAQ, jumped on board the money train and created its own market. An opportunity to raise fistfuls of cash quickly and without Congress and SEC regulations? Clearly there is momentum behind this trend.

While it isn’t clear whether the other public exchanges will come up with similar platforms, the private equity market is definitely taking off. “We feel that we’re living in a renaissance period for private equity. We’ll look back in 25 years and be amazed at how fast this asset class grew,” said Allen. He continued to say that the other exchanges “would be remiss not to” follow suit with similar platforms “because it’s one of the few higher growth areas that they’ll have access to.”

One thing to watch in the coming year is which platforms take off and which fizzle. “Each is a little different in terms of where they are in the transaction space. I think there’s room now for multiples, but in general people would rather have less places to go than more…depending on what each one brings,” explained Canaday.

When the dust settles, it will be interesting to see if, in fact, one platform trumps all the others.