Evolution in energy trading highlights need for improved risk management skills

The energy complex is becoming more complex as new players with billions of dollars flock to electronic trading platforms on exchanges and over-the-counter markets. While it’s not the only risk, price risk is foremost in energy traders’ minds as they drive oil futures to historical levels.

Carol Cole, OGFJ Correspondent

Fourth-quarter oil trading began with the NYMEX November crude contract sliding from more than $83 per barrel on September 28 to less than $79 per barrel October 8 and back up again in a matter of days.

The volatile market is just the kind of trading environment that hedge finds and financial firms relish. But are the wet-barrel hedgers enjoying the ride?

Like it or not, there’s no retreat from the trading floor. Open interest data on the NYMEX and ICE exchanges confirm as much. The burgeoning over-the-counter (OTC) market is estimated at 20 times the size of the NYMEX. Energy trading is more robust than ever.

Risk management consultants say the traditional hedgers - E&P companies, R&M companies, chemical producers, and airlines, to name a few - have little choice but to be in the trenches. However, hedging strategies are shifting.

To understand strategies in this high-priced environment, it’s important to distinguish among the market participants, says UtiliPoint International’s Patrick Reames.

UtiliPoint is a research-based information, analysis and consulting firm, with an energy trading and risk management (ETRM) practice that covers, among other things, commodity trading.

“Oil producers have an entirely different dynamic than hedge funds,” said Reames, vice president of UtiliPoint’s ETRM division. “Producers own assets, and like every asset owner, their goal is to maximize their value.”

Up until a couple of years ago, many E&P companies were aggressive in hedging their production. That was in the days when $35 per barrel crude seemed to be the top of the market, just before oil price started to accelerate. Hedging limited their ability to capture the maximum return.

“Producers heard a lot of negative feedback from shareholders, especially institutional investors. That changed the producers’ philosophy,” Reames reflected.

“Most large [oil] producers now go forward less than fully hedged,” he said. “They’re willing to take risk in an open market, especially this rising market. They’re happy to hedge only a small portion of their production and take the upside on the rest.”

Different dynamic for natural gas

Natural gas is another story. “With the volatility we’ve seen in the gas markets, most producers will try to lock in forward prices. While gas has seen a run-up over the last couple of years, structurally its much more price sensitive to short-term supply and demand dynamics than is crude. Unfavorable storage numbers, a warm winter, or a pipeline interruption can really ruin a producer’s year,” Reames added.

Consumers in the energy transaction equation, the fuel and feedstock buyers, have their own hedging strategies. “At a given price, they’ll have an idea of what profit they can make, and, if a forward price makes sense for their given market, they’ll aggressively lock it in.” Transportation intensive industries, like railroads, trucking firms, and airlines have been particularly aggressive hedgers in the last couple of years.

Never mind that oil prices are high. “Hedge funds and financial firms care little about the absolute price of the commodity,” Reames told us. “Their price horizons are much shorter than those of asset-heavy producers. Their primary interest is volatility, and they’ll act on both sides, buying and selling, and trying to forecast the extremes in order to lock in profit.”

Long-time energy market observer Peter Fusaro agrees. “It’s not the oil price level per se,” said Fusaro chairman of Global Change Associates. “Most traders focus on volatility.”

Assigning cause to daily market movements can be as risky as, well, managing risk in the first place. In an $80-per-barrel oil environment, futures and options traders want as much information as possible on today’s market moves in anticipation of tomorrow’s.

Some sort of explanation is usually forthcoming at the closing bell, but even so, it’s not always possible to find a rumor, fundamental cause or political development to explain why, on any given day, prices moved in the plus or minus column.

In a general sense, volatility is the result of more trading, and vice versa. “In the 1990s, energy prices were lower, there wasn’t a lot of volatility and not much trading activity,” the Global Change executive said.

At that time, there were only a few market participants besides the wet-barrel hedgers. “Investment banks Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley have been the leading banker interest,” Fusaro said. “All the other investment bankers - JP Morgan, Credit Suisse, Citigroup, Merrill Lynch, Deutsche Bank, and others - are playing for the number three spot.”

Many in the investment banking ranks have embraced a saying familiar among oil traders: There’s only one true hedge in a tight market, and that’s to hold physical supplies.

Recognizing the uptrend in oil markets since the 1990s, those bankers have expanded their role beyond trading paper barrels to holding physical assets, refineries, pipelines, and tankage. That gives them the true hedge - the capability to take delivery of physical oil when futures contracts expire and hold scarce wet barrels.

Beyond banking

“With higher energy prices, there’s much broader interest,” Fusaro continued. “Today, we know of more than 600 energy hedge funds. More than 200 are trading commodities. We discover 10-12 every month. Just three years ago, we were tracking 180 energy hedge funds. Now, the number is over 600.”

In terms of trading volume, the combined impact of all these additional market participants is clearly having an impact. In every month this year, the NYMEX light sweet crude contract volume has exceeded the comparable month of 2006.

“The NYMEX represents just a fraction of the trades that occur,” Fusaro continued. “It’s estimated that the over-the-counter market is 20 times larger than the NYMEX. There’s so much deployed in the sector, most over-the-counter, some offshore, some on the ICE.”

Electronic trading, as offered on the Atlanta-based Intercontinental Exchange (ICE), contributes to volatility, Fusaro believes. Open cry trading at the NYMEX is declining, a reflection that hedge funds prefer electronic transactions.

“When you look at commodities, whether it’s industrial metals or oil, it’s not just the underlying demand and supply, it’s the risk trade. There’s a high degree of speculation built into those prices.” Lim Say Boon, Standard Chartered Group

Traders may be anonymous, but the price trends aren’t. Prices in the fourth quarter continue to flirt with the historical highs of the third quarter, which economists say could throw the US economy into a recession and bring a correction to oil prices.

Lim Say Boon, chief investment strategist at Standard Chartered Group gives the US a 15% chance of recession. Boon told CNBC oil prices will also decline.

“I think we’re going to see oil back to the $60s - the $60 - $70 price range. The uptrend for oil and commodities is still there,” he said.

But Boon also cautioned, “When you look at commodities, whether it’s industrial metals or oil, it’s not just the underlying demand and supply, it’s the risk trade. There’s a high degree of speculation built into those prices.”

Eitan Bernstein, CFA at Friedman Billings Ramsey, articulated the sense of many in the analyst community. “While we subscribe to the notion that increasing global crude oil consumption should support prices above longer-term historical averages, we believe that the commodity is poised for a [roughly] 10% near-term pullback as crude oil demand growth expectations decline,” Bernstein wrote in a recent research report.

“Despite preliminary data which suggest that US crude oil demand growth has recently turned negative and widespread concerns that the current economic slowdown may turn into a full recession, many closely-watched organizations still predict above-average global crude oil consumption growth during 2007 and 2008,” added Bernstein.

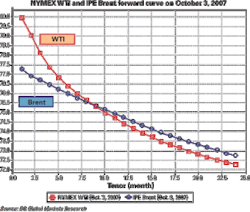

Deutsche Banc’s Global Research Team last month offered a trading strategy: short January ’08 WTI.

“With oil demand growth risks skewed to the downside in the US, we believe there is a growing risk that oil prices are now entering overbought territory,” the DB team said in a recent report.

In September, they recommended adopting a short crude oil position from the start of the fourth quarter and in October, the team continued to believe crude prices will correct lower from the third quarter, and possibly fall below $70 per barrel before the end of the year.

The analysts foresee the potential for a warm winter, fading hurricane and geopolitical risk premiums, and higher OPEC production.

“If economic weakness in the US exacerbates the already very low level oil demand growth seen in the DOE/EIA weekly oil statistics in August and September, we believe this does not bode well for oil market demand-side fundamentals.”

DB’s trade recommendation: “We are selling the January ’08 contract, rather than the frontline contract, to avoid the negative roll returns associated with the current steep forward curve.”

In the event that futures prices trend lower, how will the hedge fund money affect the decline? Rising prices are one thing. All these separate and competing strategies have worked well as oil futures climbed.

There’s no historical precedent. Never before have the exchanges been so bloated with billions of dollars of speculative funds.

Since oil prices started steadily marching higher in 2002, drawing in hedge funds in 2004, there has only been one extended downturn. In August 2006, NYMEX crude jumped to $77 per barrel on the news that BP would shut in production in Prudhoe Bay to conduct long-overdue pipeline maintenance.

That proved the peak for the year, and prices moved lower for five months. At the start of 2007, positive momentum returned oil futures, pushing them to their previous levels and beyond. Last summer’s ceiling of $77 per barrel is roughly today’s floor.

As Fusaro has said, “More energy trading blow-ups will occur.” But it’s more than just price risk. Energy trading is full of risks - credit, geopolitical, regulatory, liquidity, foreign exchange and operational risk, to name a few.

Energy risk management could be further along in its development, he said, nearer to the sophistication of foreign exchange and interest rate trading risk management practices. Part of the reason is a lack of understanding of the physical energy market.

The energy complex is more complex when it comes to risk management, he stated. Risk and reward are a “double-edge sword” in the increasingly risky business of energy.

UtiliPoint Europe’s Gary Vasey, who is based in Prague, commented that, “As energy and financial markets converge, opportunities for arbitrage and risk management increase. With greater opportunities come greater risk. Companies are investing in their risk management efforts, and the market for goods and services to support risk management programs is not only steady - it’s growing.”

Vasey added, “Our latest survey of the European market shows new players, not only financial firms, but also energy consumers entering the energy market as traders and risk managers.”

View from the credit side

Equity holders and bond holders view hedging by oil and gas companies differently. The cyclical nature of the E&P business creates opportunities and risks that equity and credit markets see differently.

“Equity analysts generally don’t like to see much oil company hedging, as shareholders frequently buy E&P stocks for their exposure to underlying commodity prices. That’s why they buy the stock,” said Fitch Analyst Mark Sadeghian.

From a bond-holder’s perspective, modest hedging can be an appropriate tool, he said. Given the oil price trajectory of the past three years, E&P companies may have drilling programs funded on expectations of $60 crude. If crude fell to $50 per barrel, there might not be enough operating cash flow to fund the drilling program going forward.

“Hedging can be an appropriate way to lock in project economics and protect the cap ex budget, especially for smaller non-investment grade credits.” Sadeghian said. “Hedging also helps stabilize cash flow, and that in turn, enables companies to make scheduled payment to their bond holders and protect their credit ratings,” he added.

“By locking in prices and mitigating that risk, you still have operational risks. If you’re natural gas producer, for example, and your wells don’t produce or you suffer a blow-out, you’re on the hook for the production you hedged but can’t deliver.” Fitch Analyst Mark Sadeghian

Speculation is another matter altogether. Constantly putting on hedges and taking them off depending upon commodity price and a changing view of the market is much more like more like trading and does not add to cash flow stability for bondholders.

But hedging is a two-edge sword, the Chicago-based analyst continued. “No hedge is perfect. There’s the basis differential to consider. And by locking in prices and mitigating that risk, you still have operational risks. If you’re natural gas producer, for example, and your wells don’t produce or you suffer a blow-out, you’re on the hook for the production you hedged but can’t deliver.”

null