Russian independents struggle for parity with majors under tax changes

Russia's independent oil and gas producers continue to struggle to achieve parity with Russian majors as investment prospects.

Tax incentives are urgently needed to put the Russian independents on a level playing field with their larger, integrated brethren. That's essential if they are to attract foreign investors seeking to exploit opportunities in Russia's rapidly burgeoning oil and gas sector.

For investors, the window of opportunity to participate in the vertically integrated enterprises largely has closed. Present investment opportunities lie primarily in the large number of undistributed small and ultrasmall fields, which are particularly abundant in the traditional oil producing regions that have a developed infrastructure.

The Russian government as well, as owner of the underlying mineral rights, has a direct interest in bringing small and midsize fields into production. The government must balance that interest against the need for transparency and enforcement of tax collection in the industry. Whether and to what extent that balance can be struck is not clear at this time.

Russia's independents are grappling with the effects of a "flat tax" that that was enacted in 2002 to raise revenues and curb tax evasion by increasing transparency in the tax accounting employed by Russian petroleum producers.

Elena Korzun, who heads the Moscow-based Association of Small & Midsize Oil & Gas Producers (AssoNeft),1 a trade group comprising 46 independent companies,2 has the task of educating the Russian government and public about the plight of the independent sector. It's a challenging task, because world oil prices have climbed to record levels, and the Russian public is already mistrustful of the petroleum industry for perceived failures to pay taxes on a proper share of its earnings.

The problem is that rising world oil prices hurt, rather than help, independent producers in the Russian oil and gas industry. This is because the Mineral Resources Production Tax of 2002 (NDPI)3 is pegged to world oil prices, but independent producers market most of their product to the domestic market, where the price is artificially low. This article examines that phenomenon and the financial circumstances in which it arises.

Market conditions

The commercial realities facing independent Russian petroleum producers can be summarized as follows:

- They are engaged in the development of small oil fields and deposits of gas field-associated condensate with low reserve levels.

- Their production is limited to a single product, such as crude oil, owing to their lack of affordable access to domestic refining facilities, owned by the vertically integrated producers.

- They have multifaceted contractual relationships involving, for example, the sharing of production with and outsourcing to contractors.

- They are hampered by lack of access to combined transport facilities, i.e., rail and water, as a means of supplying crude oil to the export market.

*Despite these limitations, they have carved a niche—at least for now—and are active in all of the main oil producing regions in the country, including Western and Eastern Siberia, Timan-Pechora, Tatarstan, and the Volga-Urals.

Collectively, independent Russian oil producers account for 7% of all petroleum production in the country. In 2003, 133 independent companies produced 15 million tonnes, or 3.6% of the national total. Tax receipts from independent producers amounted to 22 billion rubles in 2003. However, the number of independent companies and the volume of their output is in flux, due to mergers and acquisitions in the industry, and the tax system introduced in 2002 is likely to diminish their ranks further.

Notwithstanding, small independent companies are now working about 250 fields brought into production during the last 5-6 years, representing over 1 billion tonnes in total reserves, with an average depletion of 16%.

Diminishing resource base

The base of raw mineral resources in Russia is not only aging but diminishing. During 1991-2001, the number of small deposits increased by 40% and the number of major deposits fell by more than 20%. Fully 80% of all oil fields registered by the government are classified as small. Countrywide, the total depletion of reserves averages 50%, and 70% of residual reserves are associated with deposits in a late stage of development.

Annually, an average 40 fields with reserves of less than 10 million tonnes each are being discovered. Of these, 0.4% are major or "unique," 6% are large, 9.3% are medium, and 84.3% are small (representing 28.7%, 42.2%, 14.8%, and 14.3% of total reserves discovered annually, respectively). Small deposits constitute 93% of all fields and 30% of all discovered reserves in Russia. A total of 1,400 fields, with reserves of less than 1 million tonnes each, are classified as ultrasmall. The small and midsize fields mostly occur in difficult geographical or geological conditions. Up to 75% of them are classified as difficult to recover.

Such is the reserve base of the independent petroleum producers in Russia. However, independent producers also face competition from the vertically integrated companies (VICs) in the acquisition of these reserves. Although such reserves have no economic interest for the large holding companies, the latter acquire licenses for them in order to increase their company assets.

Independent producers have provided a much higher level of capital investment than the VICs, although that trend has diminished with the end of government assistance to the independent sector. In 2000, when the government still provided such assistance, independent producers brought into production 24 out of 44—fully 54.5%—of the total new fields in production. By 2002, that figure dropped to 51 out of 133—less than 40% of new fields but still reflecting a robust level of investment.

Meanwhile, independent producers are far ahead of the VICs in terms of exploratory and production drilling. Per total volume of oil produced, drilling volumes in the independent sector were three times higher for exploratory wells and two times higher for production wells in comparison with wells drilled by VICs. Whereas VICs have been completing 10-15 wells/million tonnes of oil produced, independent producers have completed 25-28 new wells/million tonnes during the same period.

Tax changes

In 2002, the NDPI was enacted4 to provide for a flat tax on production and "equal access" to the export trunk oil pipeline in proportion to volumes produced and delivered. However, the effect of the NDPI and its "equalizing" measures was to institutionalize the disparity in economic conditions facing producers in the Russian petroleum industry. Those with better fields, their own refining capacity, and access to the export market by alternative means of transport such as rail and waterway, have been handed a competitive advantage in relation to other mineral users, according to Korzun. Those particularly hard hit, she says, are the independent petroleum producers.

Prior to 2002, taxes on mineral resources production were assessed on an ad valorem basis—that is, as a percentage of the end product cost. During 1991-2001, small and independent producers paid an amount of taxes equal to about twice the industry average.

In reaction to wanton underreporting of taxable income by major petroleum companies, effected largely through the mechanism of internal transfer pricing, the government introduced a new system of tax assessment in January 2002. The new system involves the application of a coefficient that is tied to world crude oil prices.

While the simplicity of the new system was intended to result in greater transparency and accountability in the assessment and collection of taxes in the petroleum industry (and has in fact done so), it has had a disproportionately adverse impact on small and midsize independent petroleum producers, who sell only 30-35% of their output at world prices and 65-70% of their output at the domestic price, which is virtually independent of the world price. As a result, the financial condition of independent producers has sharply deteriorated (Figs. 1a-d, 2a-b).

Structural imbalance

The domestic crude oil market in Russia is highly monopolistic and lacks adequate market mechanisms. This defect results from the concentrated ownership of the production infrastructure and the lack of a commodities exchange for the setting of prices based on supply and demand in the domestic crude oil market.

Meanwhile, the trade in "free oil" is voluminous and accounts for 20-22% of total petroleum supplies to the domestic market. Production by the independent producers accounts for a quarter of that volume.

The absence of transparent market mechanisms, combined with the government's failure to deal with the problems of price formation in the crude oil market, has allowed the vertically integrated, or so-called "full cycle," companies to move their profit centers in the direction of downstream product sales to end-consumers.

Price distortions in the domestic Russian petroleum market are apparent from an examination of oil prices received by independent producers as compared with the price of refined products. Fig. 3 shows the price of grade AI-92 benzene fuel growing by 150% during 2000-02, compared with a 25% drop in the price of crude oil on the domestic market.

From November 2002 to May 2003, as shown in Fig. 4, the mineral resource production tax exceeded 50% of revenues, and for 3 months the domestic price was practically equal to the production tax (1,000 rubles/tonne and 950 rubles/tonne, respectively).

In general, the combined effects of linkage between the NDPI and world oil prices, along with sharp and unforeseeable fluctuations in domestic prices, make the economic environment highly unpredictable for independents.

The existing system of taxation, linked to a combination of world oil prices and the dollar-ruble exchange rate, results in an imbalance between the market conditions facing single-product companies, which are almost totally dependent on fluctuations in the domestic market, and those of the "full cycle" integrated producers (Fig. 5). Output by the single-product companies is thus categorized as "risky oil," with revenues $25-30/tonne less than the industry average.

Balance of crude supplies

The discrepancies between access to the domestic and export markets have left independent producers in a predictably adverse economic condition compared with the VICs.

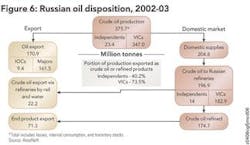

While there is parity in direct deliveries to the export market through the Transneft export trunk oil pipeline, 72.2% of the total export volume was attributable to VICs in 2002, and less than 30% to independent producers, when oil exported via railway refinery terminals (22.2 million tonnes) and downstream oil products exported by the major oil companies (71.3 million tonnes) are taken into account.

Despite its declarations of "equal access" to the export market, says Korzun, the government has legally institutionalized the advantage enjoyed by VICs with respect to the sale of crude oil outside the customs zone of the Russian Federation by all means of transport and has ignored the fact that independent producers lack equal access to rail and water transport as well as terminals outside seaports.

All of this has led to a paradoxical situation in which the VICs ship about 45% of their own product to in-house Russian refineries at artificial, internal-transfer prices, while the independent producers, lacking their own refining facilities, must not only supply around 60% of their crude oil to the same refineries at the same low prices, but also lose out on additional revenues from the downstream sale of refined products (Fig. 6).

Independents threatened

The factors described here will drive many independent Russian producers out of business unless corrective measures are undertaken, says Korzun.

These factors include the imposition of a flat-rate tax increase without any consideration of specific oil field conditions, disparity in access to domestic and export markets, and the absence of a functional mechanism for price formation in the domestic petroleum market.

As evidence of this trend, Korzun points to the net earnings of Russian independent oil producers, which fell by more than 25% during 2001-03.

On the whole, profits in the independent sector were insufficient to satisfy the demand for new investment. The deficit in invested resources, she says, has reached 300-400 rubles/tonne, or one third of the total resources necessary for payment of license fees.

And in 2003, for the first time in a decade, the rate of growth in the sector of independent producers has fallen below the industry average.

As the existing tax burden already discourages development of the independent sector, Korzun argues that any further increase of taxation will lead to a termination of commercial production in fields worked by companies not belonging to any vertically integrated group, resulting in losses of up to 15 million tonnes/year or more. At a world price of $26-28/bbl, the aggregate loss of such revenues would reach 45-47 billion rubles, she says.

Proposals

Korzun, along with a number of industry analysts, have proposed that if the base rate of the NPDI is increased as planned,5 then a negative coefficient should be introduced into the tax in the amount of 0.5-0.7, with application to independent producers. This would partially ameliorate the disparity resulting from the monopolistic conditions in the industry, she says.

In order to implement such a proposal it will be necessary to legally recognize the status of independent producers, taking into account the specific circumstances faced by this group of businesses.

Such proposals also include the recommendation for computation of a negative coefficient in application of the NPDI to fields with a high rate of depletion (greater than 85%) as well as to deposits in beginning stages of development (up to 5%).

Other proposals aimed at leveling the playing field for independent producers in Russia include the registration of producers with tax collection authorities in the regions where the relevant oil fields are located. This would allow an individualized assessment of taxation on each producer based on the particular circumstances.

Another suggestion that Korzun has introduced would be to provide independent producers with the right to obtain a ruling from relevant regulatory organizations allowing them to join a group of VICs for a given tax period.

Such measures could prove critical to ensuring the survival of Russia's independent producers, with all the revenue, resource recovery, and foreign investment opportunities that implies. ogfj

Acknowledgment

The author is indebted to AssoNeft for providing the graphics and data appearing in this article.

References

1. Assotsiatsiya malikh u srednikh neftegasodobivayushchikh organizatzii (AssoNeft).

2. Under Russian law, a company is "independent" if it does not belong to a "group of entities" within the meaning of Article 4 of the Law of the Russian Federation on Competition and Restrictions on Monopoly Practices in the Products Market. A "group of entities" exists when one entity, by ownership of 51% of the voting shares or otherwise, has the ability to control the decisions of another company.

3. Nalog na dobichy poleznikh iskopaemikh (NDPI).

4. Federal Law No. 126-FZ, Aug. 8, 2001, amending various legislation including but not limited to Part 2 of the Russian Federation Tax Code.

5. Ibid.

The author

Bruce A. McDonald is a partner in the international law and intellectual property groups at the law firm of Wiley Rein & Fielding LLP in Washington, DC. He attended Leningrad State University on a Russian language scholarship in 1976 and speaks Russian fluently. He obtained bachelor's degrees in Russian and economics from the University of California in 1976 and a law degree from American University in 1979.