What's flexibility worth? Capturing value in drilling-contract options

Options are ubiquitous in the contract drilling industry. For example:

- In December 2003, Atwood Oceanics Inc. received a contract to drill 10 firm wells plus options to drill six more wells off Egypt.1

- In November 2003, Diamond Offshore Inc.'s Ocean Heritage jack up was awarded a three-well-plus-option contract with Noble Energy Inc. in Ecuador.2

- In 1999 Maersk Oil & Gas AS issued Noble Drilling Corp. 90 days' notice of early contract termination for Noble's jack up off Denmark.3

Fixed or market-based contracts embedded with options such as these enhance flexibility for the prospector and increase the value of the drilling program. The contractor who effectively writes the options surrenders flexibility, since the possibility of early contract termination or contract extension increases uncertainty.

Using real options analysis (ROA), drilling contractors and the oil companies that use their services can evaluate and price the added flexibility embedded in their contracts.

Financial concepts

ROA applies precepts developed for the valuation of financial options to options inherent in real assets. Non-

financial options include such choices as starting up or shutting in gas wells, expanding or contracting a drilling program, and advancing or deferring an exploration program until the end of a lease term.

In the case of an offshore drilling program, a drilling contract may include an option to terminate early, an option to extend the contract to subsequent wells, or multiple options to extend the contract based on results of individual wells. All of these options correspond to American put and European call options for financial instruments.

Options in drilling contracts can provide some price protection—in the case of a fixed-price contract with an option to extend during a period of rising day rates—as well as an opportunity to minimize losses through greater flexibility. An example of the latter is a long-term contract that is terminated early because of poor geological conditions revealed by the initial wells.

Because traditional discounted cash flow or net present value (NPV) analysis measures the value of average expectations, it usually fails to capture management flexibility that exists in the real world. When there is great uncertainty, as in offshore drilling, the value of flexibility tends to be high, and ROA will reflect value better than an NPV approach can.

For the contractor, the ability to assess the value of specific contract terms represents a competitive advantage by creating the ability to offer customers a shopping cart of contract terms with their related costs. ROA techniques will also help the contractor identify opportunities that will be most profitable while leaving less profitable projects to competitors.

Decision trees

ROA builds on the NPV approach familiar to most managers. And it does not have to be mathematically complicated.

Decision trees in a binomial framework can replace the complicated calculus and calculations often associated with ROA. Armed with decision trees and the techniques of NPV, the ROA practitioner values real options just as he or she would financial ones. The essential inputs are the exercise or strike price of the option, the underlying value of the asset, a measure of the risk-free interest rate, the time to expiration, and an assessment of the volatility or uncertainty of the future value of the underlying asset.

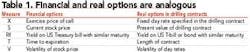

For financial options, each of these variables is readily defined either explicitly in the terms of the option contract or implicitly from observation of the market. With real options, the relevant characteristics are not so easily defined. Nevertheless, each of the inputs needed to value a real option has its analog in the financial-option world and can be determined through careful analysis.

Table 1 maps the inputs used to value a financial call option into the real-option framework. The analogous inputs become the fixed day rate specified in the drilling contract, the present value of a fixed-rate drilling contract, the length of the contract, and the expected volatility of day rates.

Drilling option

Options to drill additional wells are common in drilling contracts. They confer flexibility by allowing the prospector to drill additional wells if market and geological conditions are favorable for drilling. This flexibility has value.

We can represent this as the sum of two values: that of the fixed-price component of the contract extending to the option's exercise date and that of a second stage of the contract given the possibility that the option might be exercised. The first stage of the contract can be valued through use of simple NPV techniques. The second stage is valued with ROA.

For example, a contract might provide for the drilling of 12 wells at a fixed price with the option to extend the contract to four more wells at the same price. If it will take 30 days to drill each well at a contracted day rate of $62,400 then the value of the contract is the present value of 12 months' total revenue of $22.5 million plus the expectation of the value of the four additional wells being drilled.

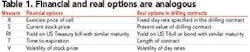

In a year's time, contract day rates probably will change. Historical measures of day-rate volatility combined with the use of the handy binomial distribution yield the event tree shown in Figure 1.4

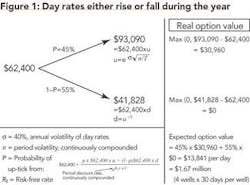

The binomial distribution is useful because as the period of interest is broken up into finer and finer increments, the expansion of the binomial tree begins to resemble a lognormal distribution (Figure 2).5 In fact, as the number of nodes in the tree is expanded, valuation of the option approaches the value predicted by the more mathematically complicated Black-Scholes call option pricing formula (see formula box, Figure 4).

The example presented here uses a one-step binomial tree to more easily demonstrate the concept at work. A spreadsheet model, however, could handle a large number of time steps with little difficulty and would more closely calculate the true value of the option.

If day rates fall below contract prices found in the market, the option to renew will not be exercised or contract terms might need to be renegotiated to adjust for the new market reality. In this situation the value of the option falls to zero but cannot become negative. If market rates rise, the prospector, by exercising the option, captures the lower rate in the original contract. The expected value of the option is therefore the probability-weighted average of these two outcomes (45%.3.$30,960 + 55% 3 $0 = $13,841).

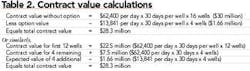

The total contract value is the present value of drilling 16 wells at $62,400 less the value of the extension option—underwritten by the drilling contractor—of $13,841 for the last four wells. Table 2 shows the calculations.

In contrast, NPV analysis produces a higher contract value: $30 million (16 wells at $62,400).

Early termination

The option to terminate early given sufficient notice is also common in drilling contracts. This is the equivalent of an American put because it can be exercised at any time before the end of the contract period.

Suppose a fixed-price, 5-month drilling contract includes the option to terminate early. During the course of the contract, day rates may move from their original level and thus, if the wells still need to be drilled, the option to terminate early effectively becomes the option to switch into a lower-priced drilling contract. The difference between the two contract values is the intrinsic value of the option at that particular point in time.

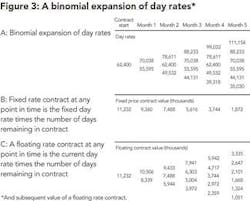

Figure 3 shows the binomial expansion of day rates and the hypothetical floating-rate contract values. Contract value is calculated as the product of the current day rate times the number of days remaining in the contract.

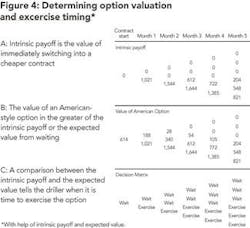

At the beginning of each month the prospector asks, "Shall I exercise the option now and receive the current payoff, or should I wait to see what happens with day rates next month?" If the intrinsic payoff is greater than the expected present value of the contract in the next period then the answer to this question is clear: Exercise the option to terminate the contract.

Figure 4A shows the intrinsic payoff of the option at each node of the tree. The intrinsic payoff is compared to the expected value of waiting until the next period. The greater of the two results becomes the value of the option for that period. By beginning at the rightmost end nodes and repeating the decision rule for each of the preceding nodes, we can populate the binomial tree with the option values for each period (Figure 4). The last value to be calculated—at the head node—is the value of the option at the beginning of the contract.

In our example, the early termination option is worth $614,000. Since the contract driller wrote this option, it is his liability, and the total value of the contract to him becomes $10.6 million (the contract value without flexibility of $11.2 million less the option value of $614,000).

Practical applications

The contract options described above are theoretical maximums. Most companies do not exercise contract options based solely on the current level of day rates in the market. This is because for short-term contracts option exercise depends more on the underlying geology of the prospect than the cost of drilling exploratory wells. Put another way: If the company does not find oil in the prospect, it will not exercise the drilling option no matter what the current day rate level may be.

The cost and effort of finding and mobilizing a new drilling rig for the remaining drilling term may also be large relative to the overall savings and option value.

ROA becomes important when the likelihood of exercise does depend on the overall drilling market. This will be the case when the overall contract term is long and the prospecting company hiring the drilling rig either has multiple prospects that it wants to evaluate with the rig or when it has the option to reassign the contract to another party. In these cases, the geology of any single prospect does not determine the likelihood of the option's exercise, and the option is more likely to be exercised based on the overall level of day rates relative to those embedded in the contract. Under these conditions the critical variables that impact valuation the most are the overall length or term of the contract, the contract's strike price (possibly embedded in mobilization fees for moving the rig to new locations), and the expected volatility in day rates.

ROA techniques are useful in valuing options embedded in long-term drilling contracts. They can help the drilling contractor determine when to cold-stack or remobilize a drilling rig, the oil field operator know when to shut in or restart production from a field, and the explorationist to decide whether and when to acquire more seismic data.

While ROA is slightly more sophisticated than the traditional NPV approach to valuation, ROA techniques are easily learned. Their greater use within the organization will help unlock the tremendous value in real assets that often remains underutilized.

Acknowledgment

Prof. Laarni Bulan of Brandeis University International Business School answered questions from the author and reviewed the article.

References

1. "Atwood Oceanics nets contracts to drill offshore Egypt, Australia," Houston Business Journal, Dec. 12, 2003.

2. Angie's Contract Drilling Weekly, Lehman Bros., Dec. 1, 2003.

3. "Maersk gives early termination of Noble jack up," European Offshore News, Jan. 27, 1999.

4. GlobalSantaFe Corp.'s monthly SCORE Report was used to generate an annual volatility measure of 40%.

5. In the binomial tree expansion, the tree's upticks and downticks depend on the historic or expected volatility of day-rate movements and, because a geometric progression is assumed, recombine in subsequent nodes.

The author

Michael Laznik worked in the energy industry as a senior economic analyst during 1995-98 for the Economics Resource Group, an economic consulting firm specializing in the energy and regulated industries. During 1998-2001 he worked in Moscow as a business development manager for Khanty Mansiysk Oil Corp. Since then he has worked as an independent consultant. He received a BA in economics and in international studies from Yale University in 1995 and an MBA from Brandeis University in 2004.