Moving at Two Speeds

Last year, Statoil CEO Helge Lund dismissed calls in the Norwegian parliament to cool down the oil sector as absurd. Yet, cooling down the oil industry seems to be the exact aim of recent proposals by the Ministry of Finance to change the Norwegian fiscal regime. With elections due in September, it seems the government has finally decided to address the question of Norway's oil industry growth. The industry asks why its growth should be restricted when it brings so much value to the country. The government responds by pointing out multi-million dollar project overruns, unresolved issues surrounding Arctic exploration, pressure on economic and human resources and a two-speed economy that leaves the mainland industry trailing behind. But how volatile has the Norwegian market really become and how is the industry circumventing these challenges?

This sponsored supplement was produced by Focus Reports. Project & Editorial Director: James Waddell. Project Coordinators: Chiraz Bensemmane, Isabella Romeo Gomez. Report Publisher: Ines Nandin. Editor: Eric Watkins. For exclusive interviews and more info, plus log onto energyboardroom.com or write to [email protected] |

LETTING OFF STEAM

In January, all seemed to be going well for the oil industry when the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy proposed a huge reduction in gas transportation tariffs by up to 90%. Naturally, this move infuriated private investors in Gassled, the natural gas pipeline system, who had only acquired these interests 18 months before. Cries of litigation have flowed from Gassled's principal investors, who now face 4% returns when they had originally planned 7% as a minimum.

But Norway's Minister of Petroleum and Energy Ola Borten Moe has maintained that lowering the cost of transporting gas to the market is essential for making marginal assets profitable, and especially assets in the Barents Sea. The tariff reductions, scheduled to appear in 2016, are a clear policy to encourage oil industry growth at the expense of pipeline investors.

Despite taking a pro-oil stance on the tariff issue in January, however, the Norwegian government made a decision in May that threatens the exact same marginal assets that the tariff cuts were designed to enable. This time, it was the turn of the oil industry to be sacrificed for the benefit of Norway's mainland industry.

The Ministry of Finance announced a proposal to raise the petroleum tax by 1% to 51%, reduce tax deductions for the oil industry to 22% from 30%, while for the rest of the economy the ministry dropped overall corporation tax by 1% to 27%. This shifting of the fiscal burden onto the oil sector marks a clear move to slow down the oil industry and balance out the Norway's two-speed economy.

On June 5, Statoil CEO Helge Lund reacted by announcing that the USD16.5 billion field development Johan Castberg would be put on hold. Indeed, the industry maintains that the removal of key tax deductions will render a large number of marginal fields uncommercial. Industry analysts have projected that the removal of deductions will push a substantial number of other fields - including BG Group's Bream field and Shell's Linnorm field - to the wrong side of the margin.

Much of Norway's competitive advantage as an oil jurisdiction over the last decade has been predicated on its fiscal stability. Undermining that stability is therefore a bold move and a clear indication that the Norwegian government no longer sees a sustainable balance between the oil industry and the rest of the Norwegian economy.

THE BARENTS SEA OPPORTUNITY

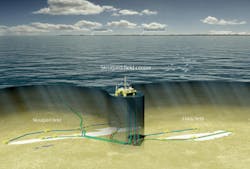

If Statoil no longer deems Johan Castberg - the largest Barents Sea field ever discovered - to be commercial, then what chance do other companies have of making commercial finds in the Barents Sea?

Chris Spencer is CEO of Bergen-based E&P company Rocksource, which was established in Norway in 2011. Rocksource is a co-owner with Total and North Energy of the Norwarg gas field in the Barents Sea. Although a promising reservoir, Norwarg looks like one of the fields that could be pushed to the wrong side of the margin by the tax change.

Spencer acknowledged that the Barents Sea is an especially challenging area, given that there is currently very little infrastructure to link a potential gas discovery to the market and that there is a high chance of finding stranded gas fields.

Nonetheless, Spencer was optimistic: "There is enough market for assets in the Barents Sea. The 22nd Licensing round elicited a very strong response and many of these companies are full life-cycle E&P players, seeking to take discoveries through to production," he said.

ATLA'S EXPERIENCE OF SHARING RESPONSIBILITY

Twenty-four ongoing projects on the Norwegian Continental Shelf (NCS) are projected to overrun their budgets, generating USD8.6 billion in losses. The BP Valhall development exceeded its projected cost by 86%. Worse, an overrun on the Ekofisk Zulu platform in the first quarter of 2013 led to profit warnings that caused a 25% drop in the share price of Aker Solutions on a single trading day.

For John Avaldsnes, global oil and gas leader of Ernst & Young, the issue lies in an overload of Norway's service industry capacity. The supply chain is faltering under the weight of USD35 billion of investment and unprecedented E&P activity. That weight is pressing on a supply industry already lacking somewhere between 8,000 and 12,000 engineers and which does not have enough spare physical capacity.

INTERVIEW WITH KPMG PARTNER JULIE BERG

Focus: What is KPMG's perspective on the proposed increases in petroleum taxation?

Berg: We do not think that there will be that significant an effect on company bottom lines. However, these reforms combined with the abrupt changes in gas tariffs for pipeline export, proposed without the usual process of consultation, are creating uncertainty in the market. This will probably have an effect on the willingness of foreign investors to invest in Norway.The other impact would be on marginal fields. It is possible that many of the plans for marginal fields could be dropped over the next 5-10 years and that would have a more significant effect on the supply industry and the smaller players.

Focus: How will this affect the juniors and independents?

Berg: These tax reforms will definitely inhibit more junior oil companies from entering the market. Whether this leads to greater consolidation of the junior companies already here will depend on the willingness of investors.

Focus: What was the rationale behind this change in the tax regime?

Berg: One theory is that the government is trying to make the oil industry more responsible for their investment decisions. The proposal is aimed at increasing cost consciousness and also aimed at cooling down the investment portfolio offshore given the current high investment level.

With the industry already hard-hit by excess demand, asking it to move even faster seems like a tall order. But a high-speed development is exactly the task that Total E&P Norge has set for the Martin Linge field. Managing director Martin Tiffen explained his objective of bringing this field on stream by 2016 - qualifying it as a fast-track development given the planned timeline from drilling to production.

Tiffen explained that valuable lessons had been drawn from their previous fast-track project on the Atla Field, and for him the most important lesson learned was the need for anticipation.

"The demand-side pressure on the supplier market simply means that oil companies need to take a little care to anticipate the availability of resources and let that guide supplier relationships, standardization practices, framework contracts, etc.," Tiffen said.

"One of the main lessons [from Atla] was that sometimes you need to be a little courageous and order equipment out of sequence," Tiffen said, adding that, "You will sometimes have to commit to fabricating a project specific part before the complete picture is in place."

"In the case of Martin Linge, we made an early commitment to a drilling rig from Maersk, because we need to start in the summer of 2014," Tiffen said. "If we had waited until everything was approved, then we would have had a great project on paper but would not have been able to drill the well in the timeframe required," he said.

Tiffen was not that concerned that such advanced planning would import risk into the business, believing that the relationships between Norwegian industry stakeholders permitted this type of early alignment.

Yet, clearly some players are going to take undue risks in this era of advanced planning. Indeed, it was the over commitment by Aker Solutions to the Ekofisk Zulu project that led to company losses and what Øyvind Eriksen, CEO of Aker Solutions described as a "brutal" reaction from the capital markets as the company's share value plummeted.

Production consultant Petrolink is one of Total's contractors for Martin Linge. Petrolink has a history of working with majors like Statoil and recently BP on the Ready for Operations activities. But it is now expanding to work with relative newcomers to the NCS such as Wintershall.

Petrolink CEO Dag Nedrum observed a broader trend of operators transferring responsibility to the service industry:

"One can see a change in the nature of contracts over the last four years. Back in 2009, the operating companies were content to buy services from many different companies. They would find a few individuals from a variety of contractors and then incorporate them into their own team. By contrast today, the operators choose to outsource the entire project scope to a contractor – essentially transferring responsibility for the management of the project to that contractor. Contracts are now made as package agreements with service companies."

This is a new era of lengthy frame agreements encompassing a much wider scope of work. In this new operational environment the service industry is assuming a larger share of project responsibility and Nedrum's advice was:

"As a contractor, you have to make sure that you are confident in your portfolio and ask for a fair price in contract negotiation. All this places greater emphasis on the pre-project planning stage."

SHARING IS DARING

The traditional relationship between the operator and the service company is being rewritten in the Norwegian-born concept of integrated operations (IO). Focus Reports caught up with Jan Nordvedt of ICT company Epsis, a long-standing developer of IO solutions, for his opinion on the rate of progress.

Nordtvedt saw that companies had gone a long way in developing the first generation of IO, which involves better internal communication between offshore and onshore facilities. However, Nordvedt felt that the second stage of IO, involving extensive cross-company collaboration, had really failed to meet the expectations that the industry had laid down ten years ago.

He explained that much of the problem was lack of a legal and cultural framework for companies to share this information. In Nordvedt's view, companies are reluctant to outsource business segments, which may jeopardize their intellectual property and he believed the proponents of IO are, "far behind where we should be in resolving this issue."

However Nordvedt acknowledged the challenge of introducing change in the middle of a major growth spurt for the offshore industry in Norway. He explained, "It is a catch-22 situation, where organizations are so preoccupied with their present challenges that they are not able to implement efficient collaborative methods, which could ultimately save them time."

AND THE WINNERS ARE…

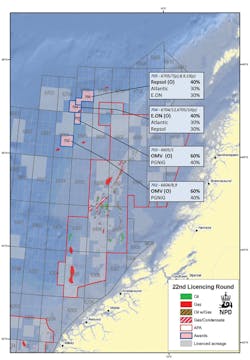

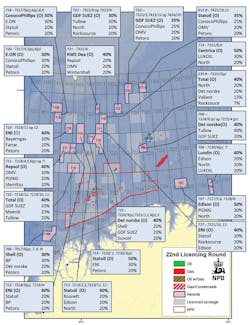

In June, twenty-four oil companies have been awarded a total of 29 licenses in the Norwegian and Barents Seas as part of Norway's 22nd Licensing Round.

The Norwegian Sea

Statoil led the pack, taking seven licenses and three operatorships. Yet Statoil was closely followed by OMV, a comparatively small player on the Norwegian Continental Shelf (NCS), which took six licenses. Indeed, OMV has recently been aggressively expanding its presence on the NCS. Six licenses also went to North Energy, a Norwegian junior with ambitions to bring value creation from the oil industry to the North of Norway. And while Statoil may have pulled out of the much maligned Russian Shtokman project at the end of 2012, this licensing round saw the arrival of two Russian oil giants onto the NCS, with Rosneft and Lukoil both acquiring licenses.

See a breakdown of the awards in the 22nd licensing round in the Norwegian and Barents Seas to the left and pg.67.

BOTTLENECKS AND INVESTMENT CHECKS

It is not for the love of flying that Norwegians are the world's number three in flying miles per capita. For anyone who has ever driven the four-hour journey on the single-lane road between Stavanger, the oil capital, and Kristiansand, the country's drilling technology center, it's easy to wonder why a portion of Norway's immense oil wealth could not have gone into putting extra tarmac on some of the country's picturesque but poorly connected road network.

Ståle Hansen of German firm DB Schenker – the largest logistics provider in Norway - described an infrastructure set-up, which had suffered from years of underinvestment. In his view, this was a result of political short-termism in infrastructure planning and it posed major problems for the oil industry.

He noted that, "Norway is very different to other oil countries in the fact that activity is so spread out across the country. For example, in Brazil there is one centralized oil hub where air, sea and land logistics companies can concentrate their investments." For a country, whose oil industry is dotted along a 16,000-mile coastline, the key to a strong logistics network is to fix key logistics hubs.

The Barents Sea

While Norway has a southern center of oil and gas activity in Stavanger, it is missing an equivalent for the North of the country. Hansen confirms, "There will no doubt be bottlenecks and slow-downs in the development of projects because of the logistics situation. The best thing that the government could do to improve this situation is to select an oil capital in the North."

The Norwegian industry can currently choose a range of cities for their Northern HQ including Bodø, Atla, Harstad, Hammerfest, and Kirkenes. Hansen fears that the lack of a designated oil hub could see Norway losing out to Greenland or even Iceland as a hub for the transition of the international industry toward Arctic E&P.

John Stangeland of Norway's leading supply base company, NorSea Group, voiced a similar perspective. The group runs Polarbase, which functions as one of the main offshore supply bases for activities in the Barents Sea. However, Stangeland explained that activity levels in this region had been a "rollercoaster" since the 1980s and that there were still major uncertainties regarding the region.

Instead of the government stepping in to make decisions, he believed it is more the responsibility of the industry to make long-term commitments.

Stangeland explained: "Since Statoil's Snøhvit was developed, the activity level has been more predicable, but still highly variable, and at the end of this year we expect some key decisions regarding the Barents Sea to be made and this will provide the basis for our future investment decisions."

But Statoil's Johan Castberg development in the Barents Sea now seems to be on the sidelines. From Stangeland's perspective, this indecision could hold back the economic development of Norway's High North. "Most of the value creation is occurring in the South of the country, and we are still some way from seeing sizeable local value creation," Stangeland said. For him, predictability is the one thing necessary to turn the Hammerfest logistics hub into an industrial cluster, capable of benefiting the region.

THINKING OUTSIDE THE CONTAINER

The 1956 invention of shipping containers was twice as effective at generating globalization as any regulatory initiative to free up international trade, according to a recent edition of The Economist magazine. Huge efficiencies were introduced by using standardized containers, which avoided the previous time-consuming jigsaw puzzle of loading different-sized cargoes onto ships.

John Naesheim, managing director of Swire Oilfield Services, the market leader in offshore containers and modular solutions, affirmed the key role that offshore containers played in the efficiency of the oil industry. However, he also noted that this emblem of logistical standardization - the container - has been receiving a distinctly Norwegian adjustment.

Naesheim said that the Norwegian market had put pressure on more tailor-made containers. "The greatest growth opportunity is in designing bespoke, special segment containers," he said and continued, "the demands of this market have actually made Swire Offshore Services' facilities at Tananger the center of excellence for his firm's product line."

Naesheim pointed out that Norway has been the center of a global drive toward more complex and higher standard cargo solutions and that Swire Offshore Services had been invited by their international clients to perform the same work in the US, UK, Brazil and Africa.

CLEANER SEAS

On March 14, Norway's Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg pledged USD500 million to support Norway's short-sea shipping segment, allowing it to take a greater role in the country's logistics infrastructure. But as Norway gears up for a major expansion in maritime transportation, European maritime authorities are preparing to implement stringent IMO Emissions Control Areas (ECAs) in the North Sea, beginning in 2015.

According to Aksel Skjervheim, marine LNG business development manager at Shell subsidiary Gasnor, the new ECAs will have a major impact on the maritime market and he hopes that it will greatly expand the use of LNG as a maritime fuel. Indeed, for the express purpose of tapping this market, Shell acquired Gasnor in July 2012.

Skjervheim explained that LNG is clearly the cleanest option relative to traditional maritime fuels: "Gas only takes down the Green House Effect by around 20%, but it takes down local pollution by 100% on particle emissions, 100% on sulphur and 85% on NOX."

Economically, the toughest competitor to LNG would be a combination of heavy fuel oil (HFO) and scrubbers, a technology for cleaning exhaust gases. Using scrubbers is currently a cheaper option than converting to LNG from an initial cost perspective. However, Skjervheim argues that the two technologies come into a similar price bracket when factoring in the total associated costs of using chemicals, storing sludge and the 2% energy drain when scrubbers are active.

Gasnor's main challenge in driving the LNG market concerns storage and infrastructure. LNG is around 4-5 times more expensive to store than oil. For him, this means that large economies of scale are needed to make LNG a competitive fuel:

"In each port you need to have around 200,000 tonnes [of LNG] being used, and you need to have a smart distribution system from the sourcing. Volume is the key factor in this equation."

Tom Cantero, managing director of US-based Air Products, likewise saw the incoming regulations as a major growth opportunity for LNG. But Cantero was not convinced that Norway's bunkering solutions currently make environmental sense:

"Currently there are clean LNG ships with no bunker solutions and which therefore require large diesel-driven trucks holding LNG containers to supply them – this is hardly a green solution."

Cantero sees a great opportunity in the dual-fuel segment (using a combination of oil and LNG), where he is counting on nitrogen generators playing a key role in purging the engine environment of potentially explosive gases in the process of transitioning between fuels.

US-based Air Products works with the LNG industry around the world and recently secured a landmark deal for work on Australian Ichthys project. Cantero feels that the company's presence in Norway has been essential for gaining insights into the future directions of the LNG industry.

"Norwegian companies are driving forward the global LNG business and it is extremely valuable to have a market presence in Norway, in order to understand their specifications,"he said.

FROM GEOGRAPHY TO TECHNOLOGY

A map of Norway reveals many of the challenges faced by the authorities in infrastructure planning, not least, Fjords that cut 20 miles into what the CIA Factbook describes as a "rugged" coastline, making road and rail infrastructure extremely hard to connect.

For Trygve Seglem, CEO of Knutsen, a major by-product of this challenging topography was the creation of a unique environment for the development of the country's maritime industry. "The country has a very long coastline, which is dependent on sea transportation to connect the regions. For me, this led to us taking a different approach to shipping to other nations," said Seglem.

Seglem believes that one characteristic of the Norwegian industry is its technical orientation. "You will see that our industry has always placed engineers in charge of companies. This led to a business culture that sought to develop the technical side of the business," he explained.

For its part, Knutsen is currently pioneering pressurized natural gas (PNG) technology, seeing it as an eventual replacement for LNG on distances of 2,000 miles or less. Seglem makes the case for this technology highlighting that PNG has the ability to transport a mixture of gases and that it does not require an expensive onshore liquefaction facility. The company is also looking to expand its work in the field of floating gas storage over the coming years.

Secluded on an island south of Bergen on Norway's West Coast, is Eide Marine Services, another maritime player focusing on developing new technologies. Eide Marine Services has a heritage in boat building dating back to the 12th century. The company's CEO Georg Eide Jr. jokes that some things have changed in the intervening 900 years.

Given the opposite trajectories of the global maritime and oil and gas markets at the moment, more maritime companies are moving into the oil industry and Eide is no exception. The company recently designed a revolutionary new hybrid light intervention vessel that bridges the gap between a ship and a column-stabilized platform.

One of these vessels is currently on contract with Petrobras in Brazil. However, Eide maintains that the idea behind this new business was never to conquer global markets. He explained, "We were looking to create more high-tech jobs on our island facilities. On the back of these projects we will be able to develop and expand our technology center." He continued, "Eide comes from a small community and instead of depleting that community of its population, we are trying to build value and attract more people to the region to work."

IT WAS BOND TO HAPPEN

Since Basel III regulations were introduced in Norway, the requirement to hold more reserve capital has restricted access to bank financing for asset-heavy industries like oil and gas and the maritime sector. According to Pal Mitlid, head of large corporates at Danish-owned Danske Bank, this restriction has led to a major new trend of utilizing the bond market to raise funds.

"This may not be to the same extent as you see in the US, but much more than has been the case in a historically bank-funded Nordic market," he explained.

Per Gunnar Ølstad, senior listing manager of the Oslo Børs and responsible for the oil and gas sector, said: "We are seeing many new companies entering the bond market, who have never taken this opportunity before."

Ølstad added that this was not just a local phenomenon and that the Norwegian bond market was even attracting companies from other jurisdictions, including the London AIM, and even private Norwegian companies. Ølstad believes that the rise of Oslo as an international bond market is helping to redefine the city's reputation as a global energy finance capital.

THE SECRET OIL CITY

The choice of Stavanger as Norway's oil capital was never carved in stone. It emerged through the work of Arne Rettedal, a highly enthusiastic Stavanger politician, who fiercely lobbied the government in the 1970s to establish the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate and Statoil's headquarters in the city. By contrast, Bergen, the former capital city of Norway 130 miles up on the West Coast, was dominated by long established family-owned businesses in the maritime and trade industries, and struggled to muster even a lukewarm reception to the "cowboys from Texas" looking to set up in Norway.

But Bergen's former mayor Gunnar Bakke pointed out that a lot of Norway's oil and gas is located in the common waters between Stavanger and Bergen. In fact, with over 60% of Norway's oil and gas fields located off the region's coastline., Bakke described Bergen as the "operating city".

Linn Moholt, CEO of Bergen-based maintenance and modification company, Karsten Moholt, acknowledged this opportunity: "Bergen is a well-kept secret in the oil industry. Many of the Norwegian modifications and operational services are conducted here and this makes the city a good place to be located as a sub-supplier."

In fact, Statoil is now shifting some of its operations from Stavanger to Bergen and Wintershall, one of the country's largest new operators, is establishing an operations base in Bergen having taken over Statoil's Brage field in 2012. Karsten Moholt is responding with a major investment project to unite all of its facilities in Bergen into one facility to better meet the demand.

Karsten Moholt also is partnering with an organization called the "uptime center of competence". Moholt explained that the organization is working on projects in condition-monitoring and supply chain efficiency with the stated aim "to make the chain 30% more effective."

Moholt believes that the combination of huge industry demand and cross-company collaboration in Bergen could put the city on the map as a major oil industry hub, reversing the cold shoulder that Bergen showed to the oil industry back in the 1970s.

RE-ENGINEERING HR

Norwegian oil industry estimates suggest a deficit of between 8,000 and 12,000 engineers, a problem that many leading companies see as the most serious threat to the development of the country's industry over the coming years.

Norwegian universities produce around 2,000 engineering graduates a year. But that is not enough when you take out the graduates who pursue non-oil industry careers and factor in the time they need for training as well as the retirement of around 50% of the international oil industry in the so-called "Great Crew Change". The inflow of foreign engineers from the rest of Europe is also blocked by a combination of supplementary qualifications and conservative hiring practices.

Kristin Færovik, managing director of Rosenberg Parsons Fabrication yard in Stavanger, explained that their former owner, Bergen Group, was simply unable to provide the extra engineering man-hours that they needed to engage in the larger projects on the Norwegian Continental Shelf. She explained that the principal reason for choosing to merge with Australian engineering giant Worley Parsons in March, was to gain access to its spare engineering capacity and headcount of over 40,000.

At the other end of the spectrum are companies like Malm Orstad with a headcount of just 100, but who face the same human resource challenges. The firm's managing director Magne Orstad said:

"The main challenge confronting our company is to find enough qualified engineers. Unfortunately, there are not enough in the market today and the growing number of service companies in Norway has generated much more competition for this talent"

Orstad is looking to take on around five or six engineers a year. Asked whether companies of Malm Orstad's size would be able to survive as access to human resources tightened, Orstad replied that the size of his company was actually advantageous.

In his view, being able to offer engineers more responsibility and control over their projects was a way to draw in experienced engineers from larger companies. "I believe they are attracted because we offer challenging but interesting work to these engineers. Often for those engineers coming from larger companies, they gain the satisfaction of having greater control over what they produce," he said.

ROOM FOR IMPROVEMENT

Finding a hotel room for the ONS is nothing compared to finding a bed on a platform for an offshore worker. CEO of Bergen-based maintenance and modification specialist, Beerenberg, Morten Walde believes that the shortage of offshore beds is a challenge for the industry and one which drives up operating costs. Restrictions in access to beds mean that offshore work will take longer to carry out. Walde explained that one of the main points of their business strategy had therefore been in "shifting the amount of work performed offshore to onshore facilities. This had lead to a huge increase in margins."

The shortage raises an important problem for training the next generation of offshore workers. In conversation with Jan Olav Nerland, managing director of Global Offshore Consulting, a human resource company for offshore work, Norway faces an ironic situation where there are literally thousands of qualified survey workers in Spain willing to work in Norway, yet they cannot take up empty positions because they cannot bank the minimum 200 hours of offshore experience on the NCS, that Norwegian employers require.

Karl Ronny Klungtvedt, CEO of Norwegian accommodation rig company, Prosafe, recognizes the problem and says that the demand for extra accommodation has been growing since 2003. He explained that this was when maintenance, modification and decommissioning really started to develop and he projects the demand for offshore beds intensifying from 2014 onwards.

CROSSING THE BORDER

Between 2013 and 2016, the number of offshore rigs operating on the Norwegian Continental Shelf is expected to rise to 52 from 35 today. But the process of bringing them into Norway is by no means simple.

"Adapting a rig to the demands of the Norwegian market is hard work which needs a careful and planned approach to avoid difficulties later," said Morten Mellerud, managing director of OSM Offshore, a company specializing in bringing newbuilds into the Norwegian market.

Mellerud elaborated: "The one key lesson is that you need to invest early in adapting to regulations rather than leave it until the last minute; it is hard to adapt a rig once you are already bringing it to the market. There have been some high profile and costly examples of rigs failing to meet Norwegian regulations."

Mellrud was referring to Talisman's announcement to scrap the Yme platform, in a USD470 million settlement with Dutch maritime group SBM Offshore. Talisman had spent more than USD1.35 billion in construction costs for Yme, which ended up falling short of Norwegian regulation and will no longer go into production.

The strong regulatory differences between the Norwegian jurisdiction and other offshore markets mean that Norwegian rig contractors will often choose to operate exclusively in the Norwegian sector or work everywhere in every sector except Norway.

Established in 2011, North Atlantic Drilling is a relatively new name in the industry. However, in essence, the firm is the harsh-environment drilling arm of Seadrill - formerly Smedvig – the first Norwegian drilling company. Seadrill's roots go back to 1971, but last year, the former flagship Norwegian drilling company, uprooted its head office and moved to London, leaving its high-latitude subsidiary North Atlantic Drilling behind in Norway.

North Atlantic Drilling CEO Alf Ragnar Lovdal explained that, "Overall the separation of the harsh-environment drilling business from the rest of Seadrill's operations has been well received by the industry as well as by our own employees." He believed that the separation between Seadrill and North Atlantic Drilling had allowed the two companies to tailor their rigs to their operational areas of focus, keeping the cost-level appropriate.

The company's main concentration of rigs is in Norway, but it is trying to broaden its focus, as its name suggests. Lovdal aims to expand North Atlantic Drilling's operations to cover the entire offshore region from Greenland, to the UK and eventually into Russian waters. Lovdal was encouraged by what he sees as the start of greater convergence in the harsh-environment drilling market. "Indeed there are aspects of UK regulation, which now are equally as stringent as that of Norway," he said.

THE HYDROCARBON PEACEKEEPER

How has Norway been able cast itself as the white dove, when it has spent the last 40 years making a nest-egg from black gold?

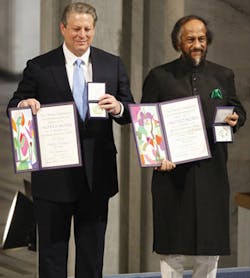

Norway has presented the Nobel Peace Prize since the award was established in 1901. But Geir Lundestad, director of the Nobel Peace Institute, says it was not until Norway hosted the 1993 Oslo Accords that the country cemented its international reputation as a peacekeeper nation.

Lundestad said, "The idea that a few Norwegians could set about and to some extent even succeed in bringing peace to the Middle East was almost absurd. Yet when the Oslo Accord was signed, it transformed the world's image of Norway. There was not a conflict in the world in which leaders did not ask Norway to participate."

But this affiliation with global peace initiatives appears to run counter to the country's involvement in oil and gas. Indeed, Lundestad was quick to point out the many contradictions between representing peace and working in an industry, frequently associated with conflict, corruption and environmental damage.

Lundestad saw these contradictions ranging from promoting low CO2 emissions as the worlds 3rd largest gas and 7th largest oil exporter to the ethical questions of how to invest the country's oil wealth, when the high yields tend to lie in industries with unethical practices. Indeed the Norwegian Government Pension Fund - the repository for the country's oil wealth - has recently been pulling out of investments in polluting Chinese companies, energy giants operating alongside corrupt political regimes and tobacco companies.

Despite these conflicts of interest, however, Lundestad acknowledged that, "The income for Norway's engagement in global peace initiatives comes from oil and gas." Indeed, it is hard to imagine how Norway would be able to sustain its commitments to global peace without its hydrocarbon wealth.

In addition, Norway appears to go to great lengths to balance oil interests with peace initiatives. Last year Norway set an increase in CO2 taxation on the Norwegian Continental Shelf to help fund a USD1 billion dollar commitment to protect the Amazonian rainforest. And finally, much of Norway's activism and self-confidence on the international stage can be attributed to its status as a wealthy country without the burden of having a colonial past.