Norway Anything But Standard

| This sponsored supplement was produced by Focus Reports. Report Publisher: Ines Nandin. Project Director: James Waddell. Project Coordinator: Chiraz Bensemmane. Editorial Researcher: Teddy Lamazere. Editor: Eric Watkins. For exclusive interviews and more info, plus log onto www.energy.focusreports.net or write to [email protected] |

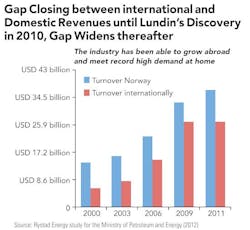

The second most valuable industry to the Norwegian economy after oil and gas production is the Norwegian oil service sector. Making a standing start in the 1970s, this sector today generates $63 billion in revenues with 40 percent ($26 billion) of that figure coming from the sale of Norwegian technologies to foreign markets. Unable to exploit any natural cost advantages, Norway's international competitiveness has relied upon the strengths of its innovations and its ability to redefine existing industry standards. But how sustainable is this endless focus on the high-tech, high-cost solution?

Volstad Surveyor Varg Brace 2.Picture courtesy of Deep Ocean

Home to paradigm altering innovations like horizontal drilling, multiphase flow, power-from-shore, 4D seismic and now "integrated operations" and the "subsea factory", Norway is the birthplace of many of the offshore industry's cornerstone technologies. The remarkable aspect of this technological achievement is that it has come from a country with a distinctly unremarkable technological heritage – known for having invented not a great deal besides the cheese slicer.

The Norwegian offshore industry has achieved this technological feat by valuing innovation over the cheap solution, whether from foreign contractors or domestic. But is Norway's pursuit of the non-standard product, which brought it so much success in the past, now simply pushing up the cost curve? By focusing on the exacting requirements of the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS) and riding a wave of cost inflation, is the Norwegian service sector now undermining its international competitiveness? Or, as the Norwegian minister of petroleum and energy Ola Borten Moe believes, are the high costs now driving a new wave of innovation?

Tethering to the Home Market

In 2012 the domestic market for oil services rose to $24.7 billion and is projected to hit $37 billion in 2013, making Norway the number one offshore investment market globally. For David Smith, managing director of offshore logistics and mooring specialist IOS Intermoor, this marks a stark contrast to the situation a few years ago.

Smith explained: "In 2009, IOS InterMoor was looking internationally, as many Norwegian companies were, to expand its business. At that time, most Norwegian companies started to think that the industry's end was in sight."

At the lowest point of the global financial crisis, the domestic base of Norway's oil service sector was in decline and companies were targeting international markets. Then in 2010 and 2011, Lundin and Statoil made their giant discoveries on the Utsira High, turning the international perception of Norway's oil potential on its head and sparking a surge of investment in the sector.

It is not for nothing that Smith regards 2011 as a benchmark year for the Norwegian service industry. "A year after those huge discoveries, most Norwegian companies' target market is now domestic," he said, forecasting a mini-boom in activity over the next 3-4 years. IOS Intermoor has responded by redirecting resources to the Norwegian market and significantly expanding on the facilities at its main Norwegian base in Mongstad,.

One of the founding fathers of Norway's export-focused oil and gas association INTSOK Håkon Skretting agreed that Norway's second oil boom has refocused attention. He explained:

"With the current booming activity in Norway, Norwegian companies had never been as busy as today on the NCS. Therefore many companies argue that there is no need to go to other countries like Russia when they have everything in their home country to prosper."

Value Creation vs. Wage Inflation:

The downside of so much investment pouring into the Norwegian market is an inevitable strain on human resources, creating significant wage inflation as companies seek to entice the country's limited retinues of engineers and offshore workers. In 2010, the year that Lundin made its giant oil discovery on Avaldsnes, labor costs rose by 12 percent and since then employee wages have increased significantly as a proportion of the industry's total spend.

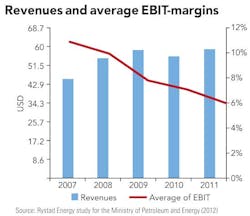

The effect on Norway's oil industry is a total lifting cost, which has climbed to around $75 per barrel, threatening to increase the threshold of what is considered to be a marginal field. However, the effect on the service industry is arguably more deleterious. Further disadvantaged in exports by the strength of the Norwegian krone, Norway's fabricators have been losing work to international competitors in countries where the cost of labor is several times cheaper.

For nine years until the 2011 demerger, Aker Solutions and Kvaerner operated as one company and the history of their collaboration dates back more than 40 years. Even after the separation, these Norwegian firms remained close allies in bidding rounds for major projects, but the conclusion drawn at Aker Solutions' Q42012 briefing was that this flagship Norwegian pairing cannot endure much longer.

The Norwegian partners lost all of their Q4 bids to international challengers as Jon Arve Haugan, Kvaerner's president and CEO, wrote in their 2012 annual report. He stated, "in the most recent round of awards, topside EPC contracts were awarded to Asian yards and jacket contracts to European yards. Needless to say, we are not satisfied with the outcome."

As Aker Solutions recognized, the key factor in losing these bids was a lack of price competitiveness. For Aker Solutions COO Per Harald Kongelf, the poor performance signaled that, "Norwegian fabricators as well as Aker Solutions need to work on competitiveness including our subcontracting strategies and relationships with suppliers." In an era where the Korean behemoths of Daewoo, Hyundai and Samsung are turning their hungry gaze on the oil and gas industry, to offset the decline in global shipping, the ‘Made in Norway' premium for offshore fabrication appears conspicuously high.

On the back of more technologically driven business units, especially subsea equipment, Aker Solutions actually enjoyed a strong 2012 with revenues climbing by $1.44 billion to $7.68 billion; the let down was based on labor-intensive fabrication. And as Kongelf announced that Aker Solutions was seeking, "more flexibility regarding our [their] bidding partners," the 40-year partnership between Aker Solutions and Kvaerner became another casualty of Norwegian cost inflation.

Losing Nemo

Better to be a big fish in a small pond than a small fish in a big one, was the rationale behind the decision of leading Norwegian contractor Apply to sell its subsea division Apply Nemo to Kongsberg last year. For Apply's CEO Peder Sortland, "The subsea segment is becoming a serious game, played by the very large subsea specialists." He explained that although a big name in the Norwegian industry, Apply did not have the balance sheet to remain competitive in the segment. Sortland sees a more general trend towards consolidation where: "Smaller, bespoke subsea specialists are becoming few and far between. The major competition is between the big players: FMC Technologies, Kongsberg, Cameron, GE and a few others. We are witnessing increased ‘productification' and standardization. As such it is hard for the smaller players to survive."

Apply has completely pulled out of a subsea sector, which is predicted to double in size between 2012 and 2016. The company will instead concentrate on its competitive position in the MMO segment, which, according to Sortland presents sufficient room to grow market share, though dominated by Aker Solutions and Aibel.

The consolidation at the top end of the market is driven by the procurement strategies of its main operators. Procurement officers are now attempting to contain costs in a new era of cost inflation by dealing with fewer contractors and transferring risk from buyer to supplier. As a result, the structure of the service industry is going through some major changes.

The Home Advantage

Norway's drive towards consolidation in the service market does not mean the end of the small players. For Stig Dahl, managing director of Dahl Oilfield Services, a downhole equipment supplier, small local players have unbeatable advantages over the large internationals in a market renowned for high standards a preference for bespoke technologies.

"As a local Norwegian company, we are aware of the advantage we have when conducting business with other Norwegian companies. Large international companies with many offices around the world cannot reach the level of influence and knowledge in Norway compared to a local Norwegian company like us - which has 90 percent of its activity based here."

Standardization may be the weapon of choice for the multinationals in cost-reduction, but Dahl Oilfield Services has opted for outsourcing its supply chain to low-cost countries like Ukraine and China to stay competitive.

In addition, Dahl explains that the stringent NS1 standards in the Norwegian market created a degree of protection for those companies purely focused on the Norwegian market. He said:

"As the standards are higher in Norway than in other countries, we realize the advantage our drill pipes have in respecting high quality standards [of the Norwegian continental shelf]".

Innovators, not Entrepreneurs:

In a wry observation, Ståle Kyllingstad, CEO of the industrial group IKM, characterized Norwegians as "innovators, not entrepreneurs." Kyllingstad described a situation in which would-be entrepreneurs were often sidetracked from the arduous and long-term commitment to their companies by the good life offered by Norwegian society. For him, Norwegian culture is the root cause of a phenomenon of Norwegian companies moving swiftly along a conveyor belt from innovation to acquisition by American multinationals. "There is something fairly unusual about Norwegian culture," Kyllingstad said. We sell our companies a long time before they do in other countries."

For Kyllingstad, the unfortunate outcome of this phenomenon is that, "compared to the technical successes in Norway the number of companies which have gone abroad and made an international success is relatively low."

For other observers, the question is not simply one of national character. Bjarte Fagerås, CEO of Octio, a Norwegian start-up pioneering the technology for permanent seabed monitoring, may represent exactly the type of Norwegian innovator about whom Kyllingstad was talking. Fagerås started up five companies prior to his present brainchild and has spent his life working with technology. However, in his view, the reason that Norwegian tech wizards sell early is not so much an issue of culture as one of financing.

"It is easy in Norway to get the first funding, because of the support from the government and various research institutions. The social welfare system also provides a safety net in case you fail in your business. However, after initial funding, it is very hard to secure funding for the next stage. The only groups who are willing to invest and who see the value are large international, French, British and American companies who take over the company."

The principal beneficiaries of this "willingness to sell" are the well-known multinational service companies like Halliburton, Schlumberger, Weatherford, GE and Cameron. Oceaneering, the global leader in remotely operated vehicle (ROV) services, certainly sees Norway as a crucial component within its global technological progress. VP & Country Manager of Oceaneering Erik H Saestad said, "Norway is an important place to look for new technologies … the Norwegian oil and gas cluster has been in the forefront with respect to developing and applying technology within areas Oceaneering operates in."

NCA Group, acquired by Oceaneering in 2011, was one of the biggest aqcuisitions for the company, and gave it a key foothold in the decommissioning market. Saestad said, "in the decommissioning market we needed the expertise of the NCA Group to complement our services to approach this market." For Saestad, the idea was to broaden the scope of operations, a key component in Oceaneering's competitive international standing against other ROV providers.

As an Ernst & Young 2013 paper highlights, broadening the portfolio is one of the biggest drivers of M&A in the global oil service industry. But in the Norwegian context there is an additional factor driving consolidation. According to Saestad, Norway is subject to "an ever-greater demand from the operators to broaden the scope of contracts, which is pushing the larger service providers to meet these needs."

This in part explains the relative aggressivness of the M&A activity in Norway over the last couple of years. In 2010 the transation market in Norway represented $8 billion, marking the start of a continual climb in M&A activity. For its part, Oceaneering's expenditures on acquisitions were almost triple its yearly average for the period 2006-10.

Whether Norwegians prefer their blue overalls to their business suits, or whether the funding model stunts growth at the point it is most needed, the tide of Norwegian intellectual capital being swept up by Western multinationals remains unabated. The pickings are just too rich to be ignored and operators now seem to demand it.

A Seismic Shift in Thinking:

Bridging the gap between the realms of innovation and entrepreneurship is a Norwegian/American business model, which has transformed the world of seismic: multi-client surveying. Not a technological innovation per se, but rather a business innovation, multi-client surveying has reshaped the relationship between governments, oil companies and seismic contractors. This model evolved in the North Sea and Gulf of Mexico and was pioneered by two companies: American TGS and Norwegian Nopec, which merged in 1998 to form TGS Nopec.

Stein Ove Isaksen, TGS Nopec senior vice president of the eastern hemisphere, explained that the model has come a long way in the last 30 years in replacing the two former models of seismic surveying. For Isaksen, the first model (proprietary seismic) involved seismic surveying work remaining a fully in-house competency of an oil company. This gave way to a model (contract seismic), where oil companies outsourced survey work to specialized seismic contractors.

TGS Nopec has been working towards building the market for the third model: multi-client. Isaksen described the functioning of multi-client surveying:

"In this model, seismic companies are the ones identifying prospective areas for seismic operations. The seismic companies will frequently conduct seismic surveys with only a part of the cost underwritten by oil companies and so will be exposed to financial risk (the level of which will vary depending on the proportion of oil company commitment obtained). In this system, the profitability of seismic companies is fully dependent on the attractiveness of the data they generate, and the number of oil companies that are willing to buy these data."

Isaksen describes this business innovation as a win-win-win situation, referring to the three principal stakeholders benefiting from the model: governments, oil companies and seismic contractors. For governments, the multi-client model means that seismic data is no longer the exclusive property of a handful of oil companies, but sold to whomever is willing to pay. Because the initiative is undertaken by seismic companies, governments can open up unexplored frontier E&P areas faster, thereby providing an early stimulus for investment.

In a study by consultants Wood Mackenzie, multi-client data has actually been shown to lead to a greater number of exploration wells and to the collection of ten times more seismic data, compared to traditional contract seismic. Isaksen explains that this is because the incentive models form multi-client are very different to contract seismic.

"Oil companies are seeking to minimize their expenses on seismic surveying. Therefore, when an oil company makes a discovery following a seismic survey campaign, they have a tendency to high-grade the assets early and perform minimal additional surveys in the immediate area around the discovery. In the multi-client model, the incentives are the opposite. Multi-client seismic companies seek to maximize interest in their data by covering as wide an area as possible and producing as much data as possible."

The Path Towards Commercialization:

Former CEO of Norwegian flow-assurance company Roxar (bought by Emerson in 2009) Morten Tønnesen did not see the sale of Norwegian intellectual capital as inevitable. To the contrary, for Tønnesen, the gap between innovation and commercialization in Norway was actually one of the easiest in the world to bridge and it should, in theory, be easy for companies to go it alone.

However, Tønnessen observed that too often on the road to commercialization, Norwegian oil service companies fell into certain pitfalls, one of them being a tendency to become overly reliant on Statoil funding.

"The Norwegian market is big, but not big enough…[service companies] become complacent, pleased to have Statoil as a client and then they just sit there supported by the funds from software sales and recurring maintenance revenues."

However, he warned against the other extreme of listing too early on the stock market, letting financiers dominate the strategy, killing innovation, and eventually forcing a sell-out to international service companies. In his view, this was the fate of Roxar.

For Tønnesen, the solution of how to commercialize Norwegian technology successfully abroad lies in Norwegian companies pooling resources, establishing networks and common marketing budgets.

"Funding is not where the problem lies since that is readily available," said Tønnesen. "It is more in the area of overlap where work is needed: smaller Norwegian companies do overlap too much on the administration, marketing, sales and distribution side of things. So, we can all benefit from coordination and partnership on this."

Isaksen continues: "From an operator perspective, the cost of obtaining data is reduced with the financial costs being spread among multiple buyers. However, this model changes the nature of competition between oil companies, which no longer compete over the data itself, but over the interpretation of the data."

The model also works out better for the seismic companies, according to Isaksen. "When the model functions correctly and depending on the attractiveness of the data, a seismic company can potentially earn a lot more from a seismic survey since they have multiple buyers."

However, despite all of the benefits of this model, Isaksen pointed out that there were challenges in gaining acceptance for multi-client in some countries. In any country with a monopoly on production, there are not enough buyers for multi-client to make economic sense nor can the model function in any country wishing to restrict information about its resources. This makes it apparent why multi-client grew out of the mature and open-access production environment of the North Sea.

However, for seismic companies to move into this mode of operation marks a significant break in their traditional way of working. Norwegian seismic company Spectrum moved into multi-client work completely when it acquired CGG Veritas' multi-client 2D library in 2011. Spectrum president and CEO Rune Eng explained that while investors in the UK, the US and Norway appreciate the asset-light nature of their multi-client business model, seismic companies are working with a greatly increased risk-profile.

Eng said that multi-client seismic companies are transforming themselves into early explorers by conducting surveys in areas, which they predict will become interesting to oil companies years down the line. "We think and act very much like an oil company in the early phase of exploration… If you had asked anyone five years ago whether Lebanon or Israel would be hot spots for exploration, people would probably have laughed at you. Today, this is truly a major E&P region thanks to Noble's gas discovery in the Levantine basin…We have recently been opening up Brazil's Northern Margin, which will likely come up in the 11th licensing round."

Multi-client companies are taking on more financial risk, because oil companies do not underwrite the costs of exploration. In theory, the profitability of these companies could be completely undermined by a range of political risks including policy reversals, regional instabilities and environmental disasters, among others.

In addition, the profitability of these companies depends on the company's ability to sell the data. Eng said that, "we have to come up with our own exploration stories and think like an oil company. To this end, we have employed three former exploration managers from oil companies. They are the ‘storytellers' in our company and they have more credibility, having worked for the oil companies."

Yet despite the challenges of adaptation, the multi-client model is gathering momentum, and it looks set to rapidly expand on what Eng believes is already a $2 billion market.

Norway's Fixed-Asset Predilection:

"You might ask, is the Norwegian oilfield service industry different from those in other countries? I would reply that in Norway, service companies like owning fixed assets: rigs, ships, heavy machinery, etc," explained John Avaldsnes, global advisory oil & gas leader at Ernst & Young.

He continued, "Norwegian service companies have traditionally taken more risk or have been more opportunistic than other countries. At the moment, this can be an advantage for us because we do have the assets to supply to Brazil, West Africa, etc already on the balance sheet and there is no need to request financing for new assets."

However, this predilection for fixed assets and acceptance of risk has been the undoing of several formerly successful Norwegian companies. One of the most notable financial falls from grace in recent years was the situation in which Norwegian FPSO designer Sevan Marine found itself in 2011. Sevan Marine president and CEO Carl Lieungh contrasted what he viewed as the remarkable success of pioneering a completely new innovation to global players, such as Petrobras and ENI, against the huge financial black hole engulfing the company just before he took over.

Lieungh admitted, "when I joined the company in May last year, I understood the job would entail restructuring Sevan Marine, but I really had no idea of the magnitude of the task I was taking on." After exhausting the possibility of a private placement, Lieungh moved towards the bondholders including Jens Ultveit-Moe, one of Norway's largest industrial investors and one of the key figures in the restructuring of PGS, Norway's flagship seismic company.

The main challenge facing Lieungh was that, "the company was not financed from the top on a fleet level, but rather the bonds were assigned to individual vessels. Each bond-holder had their own agenda. An important step in facilitating the process was the bond-holders reaching agreement on a common set of financial and legal advisers to harmonize the company's restructuring." Eventually, in the autumn of 2011, Canadian ship-owner Teekay offered to finance the entire restructuring of Sevan Marine and the Sevan Voyager, an offer that Sevan Marine's bondholders accepted.

As a result of this cooperation with Teekay, Sevan Marine has changed its business model completely, moving away from the Norwegian tendency for fixed assets. The company transformed "from a build-own-operate model to a design and technology company and project developer. Sevan Marine is now concentrating on concept studies that will lead into feed studies and a license contract like the project for ENI's Goliat Field."

Seismic contractor Seabird Explorer, which similarly found itself over-leveraged on its assets, is another company abandoning the fixed-asset predilection. Dag Reynolds, founder and CEO of Seabird Explorer, explained that the 2D seismic market is buoyant, but highly volatile. He said: "When there is an upswing we swing quickly upwards and this explains the strong performance in Q3. However, in a downturn we nose-dive and this is why we have been working on making the company more scalable."

Reynolds continued: "In a good market situation, we want to increase our capacity, but we do not want to add fixed assets to our balance sheet. We are looking to be more opportunistic and have more short-term contracts."

Seabird Explorer has therefore switched to a tactic of chartering vessels and focusing on operating them as efficiently as possible. For Reynolds,"Seabird has some key strengths within the market, and I would say the principal value is that we can take 2D vessels and operate them more efficiently than anyone else. For example, we can operate a seismic vessel at less than 50 percent of the cost of a PGS-operated vessel, and this gives us a significant market edge." This comes in especially valuable given the current oversupply of seismic vessels and low contract rates.

There is also an external factor limiting the Norwegian tendency to add large assets to the balance sheet: limited bank financing. The withdrawal of many European banks from shipping finance and the introduction of Basel 3 regulations is restricting access to capital for many players in the maritime industry. However, Sveinung Stohle, president and CEO of Norwegian LNG specialist Hoegh LNG, outlined the variation he saw in asset financing:

"Particularly in Europe, the financial markets are challenging, however last week we raised $250 million in bank debt for the Lithuanian project, showing that despite banks choosing not to lend to any shipping company at the moment, Hoegh LNG can still receive money. This is because we are not strictly in shipping, but in energy and infrastructure in long-term contracts."

Hoegh LNG has been moving from LNG carriers into floating regasification and storage units, pioneering a market, which four years ago did not exist and recently winning major contracts in Lithuania and Indonesia. Particularly in relation to Southeast Asia, Stohle sees his company assist the regionalization of LNG markets, allowing consumption to occur in the same region as production for the first time.

However despite these ambitious projects and the growth of the LNG market, Stohle admits that he does not have the all the financial capabilities needed to expand as he wishes. Financing assets upward of $300 million is a challenge in the current financial environment even if your business model is favored by the banking sector. In order to expand on his capital options, Hoegh LNG therefore launched an IPO in 2011, in line with a growing trend for Norwegian companies to focus more on the bond and equity markets, rather than the traditional banking sector, to finance their assets.

Automobiles and Standardization:

With service companies being asked to ramp up their throughput at the same time as reducing their prices, John Avaldsnes, global advisory oil & gas leader at Ernst & Young, feared that they would have to sacrifice their margins. He said:

"As companies still try to increase throughput and grow their operational capacity, more pressure is being placed on margins. At some point, these suppliers will have to make some arrangements with the oil and gas companies or their own suppliers in order to produce sustainable margins."

Eirik Bergsvik CEO of Norwegian downhole equipment and plug supplier Interwell and former managing director of the Norwegian/American giant National Oilwell Varco (NOV), explained that industry clients were aggressively trying to negotiate down supplier contracts, thereby reducing the topline for the supplier industry.

"[They] claim oil service companies are setting their prices too high. In fact, we are not the ones responsible for this, but rather our country's wealth and standard of living. Cost drivers are therefore outside of our control, and when companies like Statoil or ConocoPhillips attract employees with high salaries and social benefits, we must align with them if we want to find the talent we need."

Moreover, Bergsvik explained that operators were not willing to see any reduction in standards, which could potentially lead to a fall in costs."The fact is that if we genuinely believe that these standards cannot be compromised, then we must simply accept higher cost levels and move on with our work."

Bergsvik explained that his company had been working on expanding the supply chain to low-cost labor countries, however he believed that this would not be enough. Bergsvik saw the greatest potential in standardization and took inspiration from the automotive industry. He explained that two cars could:

"Look identical but one will cost $10,000 and the other will cost $30,000 because under the hood and inside, certain elements have been tweaked to optimize the performance and comfort of the car. Cars now contain a large number of add-ons pre-installed, which you cannot use unless you pay for them. It is cheaper for the manufacturer to supply the add-ons even when they are not paid for because of standardization."

Bergsvik saw the possibility of applying this thinking, even to the downhole industry, even though every well is different. In Bergsvik's view, by manufacturing products with a broader operational span, he could even apply "add-on thinking" to downhole plugs, having previously tried to apply this thinking to NOV during his tenure there. In cooperation with Samsung Heavy Industries, Bergsvik was pushing to standardize the drilling packages delivered by NOV in order to increase efficiency and reduce cost, in its international business.

Current NOV Managing Director Tor Ramfjord is the beneficiary of this push towards standardization to a certain extent. NOV is Norway's tenth biggest exporter and much of its business depends on the link with Southeast Asian Shipyards – Daewoo, Samsung and Hyundai. Ramfjord explains that there has been a shift in the operational model over the last ten years. He said:

"The whole business model of constructing for the oil and gas industry has changed from drilling contractors being at the center of the value chain, managing vendors and shipyards, to them only establishing the specifications and negotiating frame contracts. The rest of the responsibility has been transferred to the shipyards for a turnkey delivery of a rig or drillship."

For Ramfjord, the effectiveness of this model has come from generating standardization in drilling packages and removing the drilling contractors from the production process. He believed that rig contractors were so obsessed with trying to optimize everything that the fabrication slot was often missed and projects overran.

Ramfjord sees the necessity of maintaining a delicate balance between standardization and innovation. He said: "Our success will depend on a combination of standardized products and tailor-made equipment. In the past, Norway probably favored tailor-made equipment too much."

He continued:

"Korean yards are excellent at managing the different vendors, procuring the equipment and delivering a rig. We have an extremely successful track record working with these yards. Between 2007 and 2011, 38 deepwater rigs have been delivered on time from Korea using NOV's complete packages."

The Korean market has grown over the last decade to become Norway's largest export market for oil and gas services, ahead of the other top-five markets: Brazil, the UK, Singapore and Russia. This relationship has recently been strengthened by the collapse of global shipping Korean yards have had to make a challenging transition into the offshore market, partnering with Norwegian suppliers to gain access to high end technologies. The high volume work given to this successful international partnership is helping Norwegian contractors move towards more cost-efficient standardization.

Clustering Around the "Drilling Bay"

Tucked away in the verdant region of South Norway, near the city of Kristiansand, is a technology cluster that has transformed Norway's position as an exporter of drilling technology. Following NOV's acquisition of Bjarne Skeie's Hydralift and the establishment of Aker Solutions, a cluster of companies has transformed this area into what is now known internationally as "the drilling bay", producing around 85 percent of the world's offshore drilling packages.

Part of the success of this region comes from the collaboration of companies within the Norwegian Offshore Drilling and Engineering (NODE) cluster, which was established in 2006. Since then the cluster has grown to 9,000 people from 1,500 and revenues have climbed to $45 billion from $5 billion. NODE is one of 12 Norwegian National Centers of Excellence and is a big draw for companies seeking to gain access to key Norwegian intellectual capital.

In 2012, a third major player joined this cluster, when global leader in flow equipment Cameron made a NOK 1.55 billion ($270 million) acquisition of TTS Group's drilling division in Kristiansand. Through this merger Cameron gained work on drilling packages for the ultra-deep-water drill ships allowing Cameron to seriously compete with both Aker Solutions and NOV.

Cameron's global CEO Jack Moore saw the acquisition of this Kristiansand based company as an essential component in moving into a tough ultra-deep-water drilling market. And curiously, the company which recently awarded Cameron with a major drilling package contract, Sigma Drilling, is backed by none other than the founder of Hydralift Bjarne Skeie.

The Paternal Role of Statoil:

Though the complex production challenges of Norway apparently serve as a muse for the creation of new technologies, they are not exceptional. So why then did Norway become the center of excellence for all things offshore?

For Lars Mangal, chief commercial officer of Welltec, a lot depended on how the operators chose to focus their attention and he believed that in the case of Norway it was Statoil's leading role in seeking to maximize recovery, which allowed this Danish pioneer of well-tractor technology to develop.

"From the very early days in Norway there was a strong focus on maximizing recovery which became the overriding driver of why production maintenance and well work activities have been so strong here compared to other markets," he said.

Norway has been at the global forefront of techniques to increase oil recovery and horizontal drilling, techniques which were enabled by Welltec's technology. Øystein Michelsen, Statoil's executive vice president of drilling and production in Norway, explained that his focus was on taking the recovery factor to over 60 percent, further widening the gap between Norwegian ambitions and global standards.

For Mangal, this drive has, "forged a partnership between Welltec and Statoil from the very early days to bring technologies that were going to complete the portfolio, enable the step change and support continuous strides to improve the recovery factors from the offshore NCS."

Håvard Devold, group vice president oil & gas upstream of ABB, similarly believes the answer lies in the innovative environment established by Statoil, Petoro and the international majors at the dawn of the industry in the 1970s. He explained:

"The entire regime was designed to favor the development of the supplier industry. The positive environment was not just about Norwegian suppliers being favored in tenders; the system was set up to allow for ‘active mentorship' of the supplier industry."

Devold contrasted the Norwegian environment with that in other jurisdictions where risk-averse attitudes predominate and 5-year proven track records are demanded -- even to this day. Devold believed that unlike other jurisdictions Norway was willing to test out technologies, which would take years to penetrate other markets. He highlighted the example of ABB's first major project with Statoil:

"Our first significant project was to install the control systems for Statoil's Gullfaks platform. Working with Statoil, we had the opportunity to develop our latest control system into a fully distributed control system architecture. It took a further 20 years for these control systems to reach full maturity in other markets."

Devold saw this trend continuing with new projects like Statoil's subsea factory and integrated operations. Asked whether he saw the same type of active mentorship with the newcomer operators on the NCS, Devold replied:

"The minor companies do not have the same approach to technology. They have their own role in developing resources, which require a more lean and mean approach. As a consequence, their approach to development is much more similar to other places in the world from Southeast Asia to Africa, and they take fewer risks in trialing out new technologies."

Whether the newcomers and the minors are willing to invest in technology or not, the list of companies choosing to invest in new technologies is definitely not restricted to Statoil, Petoro, ConocoPhilips and a few other majors. The Norwegian tax regime has proven to be a major success in encouraging research and development in Norway. The state SkatteFUNN scheme, established in 2002, allows companies to offset innovation costs through tax credits. This scheme allows for intramural expenditure of $950,000 and funds for partnerships with research associations potentially receiving up to $1.9 million.

While not the largest incentives in the world, this innovative tax regime has seen companies claiming back more than $200 million in deductions and has boosted research and development (R&D) expenditure. For service companies, this has created a climate of innovation in Norway. Wolfgang Wandl, managing director of Viking Seatech Norway, commented on the willingness to adopt technologies between Norway and the UK. Wandl said:

"There have been cases where we presented ideas to an E&P company in the UK, and the UK office asked the Norwegian sister company to test out the product first before it would be used in the UK. Norwegian companies are apparently more willing to try out new ideas, and several of our products have been supported by Det Norske, Statoil and other Norwegian players."

In developing a pre-lay mooring technology for the NCS, which effectively cuts the rig move time from four or five days down to around four hours, Viking Seatech is focused on innovation for the sake of efficiency. Wandl reported that thanks to using this technology, Norwegian junior oil company Det Norske would be able to drill one extra well over its rig contract period. For Wandl, these efficiency-driven innovations alone are enough to create demand.

"Norway is an efficiency driven market," he said."In Norway, workers do two weeks on, four weeks off and in the UK they work two weeks on and two weeks off for the same pay. When labor and rigs are under-supplied to the market, the only solution to maximize on these limited resources is to be efficient.

In the UK, they work to a minimum price and it may mean standing off four or five days during the winter. In Norway, they instead say: tell me what you can do to have zero days off. If Norwegians can eliminate inefficiency, they will do it – no matter the cost."

This willingness to trial new innovations has been extremely useful for Norway's own service industry in its international expansion, a point highlighted by Even Gjesdal, CEO of Norwegian mud cleaning technology company Cubility.

"Even though the validation process of a new technology entering a market is long, especially in Norway, we feel that the recognition of our technology from the leaders of the NCS will give us the support to continue our quest in other waters. Statoil is crucial to our technology, and we are aware that other companies outside of Norway trust Statoil's choices for newly implemented technologies."

Gjesdal emphasized that Norway had managed to resist the strict financial target to retrieve oil rapidly and move on. "We believe Norway to be the best place to start our technology on its international road to success," he asserted.

Shell Technology Ventures has recently committed to spending several hundred million dollars on emerging technology companies on the NCS. So, it appears that the spirit of active mentorship is far from dead, even if the composition of operators on the shelf is evolving. .

Marginal Fields Need More Services

One of the concerns for the future of Norwegian R&D funding is that the fields being discovered are smaller than the giant developments of the past. Therefore, the focus of companies will be on the economic development of fields, not on piloting risky new technologies.

However, Erik Haugane, CEO of Norwegian junior Det Norske sees the challenges of smaller and trickier fields as more of a call to action for the Norwegian service industry rather than a omen of its demise..

"As a more mature province, which we expect to be in 2020, we will need fifty fields to produce two million barrels. So, the number of engineers and service companies necessary will increase, and there will be less oil per well. This means that the oil service industry will grow significantly. The supplier industry will take a greater share of national value creation."

In Haugane's conception, the onus of technology development will fall more on service companies themselves, and they will take a greater share of the work of production, thereby redefining their relationship with oil companies. So whilst there may be less money for oil companies to spend, the demand for services is unlikely to subside.

The Brazilian Statoil

The idea of using international partnerships to nurture the development of a strong domestic service industry is nothing new, and it forms the main motivation for every local content policy. However, no country has come close to developing a service sector as strong as Norway's on the back of international collaboration. Brazil, nonetheless, is making a stab at it and engaging with Norwegian partners in the process.

Chairman of the Brazilian-Norwegian Chamber of Commerce Terje Staalstrom said that there were around 130 Norwegian companies operating in Brazil, 100 of them in the oil and gas industry. In fact, oil and gas represent roughly two-thirds of the real trade balance of $1.7 billion between the two countries. However, Staalstrom admits that,"the biggest challenge is for companies to meet the requirements for local content… we [Norway] had similar prerequisites for local content in the late 1970s and early 1980s." However, today the Norwegian sector has matured to have more than 50 per cent foreign ownership.

Oftentimes, it seems that Brazil is prioritizing local content even at the expense of their own ambitions, with a restricted labor force undermining significant projects. Those projects, which do proceed, employ Brazilian employees on extremely high salaries. Staalstrom mentions that, "to build an FPSO in Brazil today may be double the price of Korea, and even 20-30% more expensive than building in Norway." Brazil is now far from a low-cost country in which the international service sector can establish itself.

Though onerous local content regulations provide a significant impediment to Brazilian-Norwegian service sector cooperation, the Brazilians have adopted one aspect of the Norwegian formula reasonably well: active mentorship.

Sevan Drilling, the spun-off drilling division of FPSO designer Sevan Marine, has managed to build a strong partnership with Petrobras. It was Petrobras which first took on the Sevan Marine FPSO in 2004. It was Petrobras which then took the initiative to develop the Sevan design for a potential drilling rig. And it was Petrobras which awarded Sevan Drilling (then part of Sevan Marine) the first contract for the Gulf of Mexico and then a second contract in 2008.

John Willman, CFO & Deputy CEO of Sevan Drilling, explained:

"Petrobras has been extremely supportive of both Sevan Marine and Sevan Drilling. Without this company, it is clear that neither company would be in the market today. Petrobras took a bet on this company, awarding contracts without any track record, which is pretty bold, and they have been extremely important in developing this company."

The first unit, the Sevan Driller, suffered severe cost overruns due to what Willman saw as unrealistic expectations placed on COSCO shipyards. Nonetheless, Petrobras stuck by the technology. Willman believes that the Brazilian company should have been able "to propose discounted rates for these drilling units because there was no buyer competition for this untested concept." However, the project needed to attract financing to get off the ground and Willman believes that "the agreement was reached in order to prioritize the development of this concept, rather than cost savings for Petrobras."

Despite its challenges, the Brazilian market is still projected to be valued at/worth $42 billion in 2015. So, the draw for the Norwegian service industry is evident, and in spite of local content regulations, Petrobras seems capable of championing the types of high-end technology produced by Norway over cost efficiency – thereby adapting Statoil's role on the NCS for the Brazilian market. Brazil is just setting out on a path Norway took 40 years ago. So, time will tell whether it succeeds in replicating the Norwegian forumula.

In-Norway-tion

Recent criticisms about Western economies have often been centered on whether these countries are still innovating and adding economic value. With Asia spending almost double that of Western economies on research and development, are we about to witness a steady tide of value creation flowing towards Asia?

Not so, said Henrik Madsen, Group CEO of Norwegian foundation DNV.

"I would not agree that there is a lack of innovation in Europe, I believe the opposite is true. Even if spending in Asia is much higher, Europe has an educational system and philosophy which is strong in promoting innovation; in Europe you are allowed to fail and this means that people are more willing to take bigger risks. Europe will survive as an economic power because we remain at the forefront of innovation."

Madsen went on to point out the distinguishing feature between Western and Asian innovative models. Westerners are more prone to the creative destruction or Schumpeter model of value creation, where ideas are created and destroyed with the success of their host companies. Asia tends to adopt more incremental innovation model, where innovations are slowly established within a few continuously operating research centers. As a consequence, according to Madsen, "Asia does not have the same number of small entrepreneurs willing to develop their ideas."

3M: Applied Innovations

Probably best known as the people who make office stationary, 3M has an incredible depth of technologies ranging across many industries, from healthcare to oil and gas. In fact, 3M has been nominated as the third most innovative company in the world after Apple and Google by Booz & Co. Focus Reports therefore caught up with 3M VP and GM of Oil & Gas Jeff Lavers to ask what Norway's innovative oil industry represented within this industrial constellation.

FOCUS: What is Norway's Role within 3M's oil & gas innovation?

LAVERS: Norway is a primary market for 3M globally, for the very fact that it is a key site of innovation in the oil and gas industry. Norwegians value technology, and they are adept at building new technologies – traits that are extremely valuable for a technology-driven company like 3M.

Innovation is the magical blend of invention with practical application and to be truly innovative, you need to have that mix. By continuing to work in the Norwegian market in an industry like oil and gas, our ability to innovate on a global level is much higher than it would otherwise be.

One of the main issues that 3M is facing as a company right now is that we have traditionally used the approach with products defining the market. However, the market dynamic is playing an ever more important role in steering the company, and we are now starting to see within 3M a shift towards allowing markets to increasingly inform our innovative processes.

FOCUS: How does Norway fit within 3M's oil and gas brand recognition?

LAVERS: 3M's strategy is to target the early adopters to see how products can benefit our markets, and then try to replicate this success with the other companies in the industry to build a broad base of acceptance.

We have identified some regulatory developments as "one-offs", where they arise out of a particular local dynamic, but they will not be replicated in other parts of the world.The interesting thing about the various regulatory and technology fronts in the Norwegian market, is that they are actually replicated in other markets.... Norway has a leadership role in the industry.

FOCUS: As a major consumer of hydrocarbons, how would you describe 3M's own relationship with oil and gas?

LAVERS: If you look at the recent trends in US gas prices, which have dropped dramatically simply because the industry has managed to become more efficient in extracting gas, this has delivered huge savings to American industry. As a major industrial consumer, 3M has gained a lot from this price movement as our variable costs have gone down and we have been able to use these savings to fund more R&D investment and commercial opportunities.

3M, as a company, does consume a lot of oil and gas both on an operational basis and as the feedstock for a lot of our products. This makes our search for efficiencies a circular initiative. We are often looking to benefit as a company from the same efficiency-driven products that we provide for the oil and gas industry.

Madsen continued on the subject of where value would be created."DNV has made two commitments to value creation in Norway and the first is that the headquarters of the organization will always remain in Norway. Secondly the majority - 80 to 90 percent - of our R&D will be conducted in Norway."

He clearly saw Norway maintaining a dominant role in the world of innovation. However, one of the telltale signs of an industry running low on in-house value creation is the tendency towards mergers and acquisitions. Looking at the risk management sector over the past couple of years, DNV has merged with Kema, Scandpower has merged with Lloyd's Register and, most recently, Safetec has merged with ABS. So is this a sign that value creation is suffering in Norway?

Bjorn Inge Bakken, CEO of Scandpower, sees it differently. For him, Scandpower's merger with Lloyd's Register in 2009 brought with it great opportunities to launch joint international projects. Even in the field of Arctic R&D, Norway is far from alone as a source of expertise and Bakken highlighted the joint research potential:

"Given the country's strategic positioning in the Arctic Circle, Norway is still our focus in technology development for Arctic environments… However, even here the R&D for Arctic environments is shared across Russia, Alaska, Canada and Norway. These different research environments can be leveraged to benefit our work in Norway."

Expanding from a relatively small base of companies in 2009 to more than 35 offices today, Scandpower accelerated its internationalization by integrating with various subsidiaries of the Lloyd's Register group.

"Ten years ago the Norwegian staff represented around 75 percent of our employees whereas today they represent around 30 percent. In addition, we have global centers of excellence such as Lloyd's Register's Global Technology Center in Singapore and in Southampton."

Value creation is clearly moving into an international arena for Scandpower. However, the most recent merger between ABS and Safetec shows yet another mode. ABS and Safetec have not integrated to the same extent as Scandpower and Lloyd's group. According to Jan Morten Erstaas CEO of Safetec and Vice-President of Offshore Oil & Gas, ABS Group the value of the merger comes from sharing knowledge and methodologies.

"We have not physically integrated with ABS Group, and the management of Safetec has been fully maintained. Safetec is an ABS Group company, but we have maintained our brand name and recognition in the market. We are simply looking at how the two companies can benefit from each other's experiences and methodologies. We are concentrating on how to share knowledge."

For Safetec, Norway therefore remains the hub of R&D. Rather than transferring to a new location, innovation is becoming globalized, and while that might threaten Norway's dominant position in certain fields, it does diminish its role in innovation overall. Particularly, in the case of ABS and DNV, Norwegian expertise remains at the center of global innovation.

Funding Norway's Innovative Future:

Despite the private bent of the Norwegian model of innovation, the Norwegian state is regarded as playing a major role in the development of new technologies. State funding to the oil and gas sector is delivered through two principal funding bodies Petromaks and Demo2000, which distribute a budget of $70 million to the industry. Petromaks handles all funding for basic research, while Demo2000's rationale is to co-sponsor pilot projects for applied technologies. Anders Steensen, program coordinator of Demo2000 explains:

"Government spending has traditionally been a major part of R&D spending in Norway and has played the role of encouraging private sector investment in innovation… From Demo 2000's inception in 1998, the export of Norwegian technology in the oil and gas business has increased from 30 billion NOK ($5 billion) to 152 billion NOK ($26 billion) today."

Steensen believes that the majority of the success can be attributed to the involvement of the private sector in the technology forum, including a range of players from Statoil to Total and Lundin. This involvement helps to keep public funding directed at the most useful technologies.

Anna Aabø of the International Research Institute of Stavanger (IRIS) agreed "One of the strong aspects of the Norwegian R&D environment so far has been the applied nature of our research in oil and gas."

Aabø emphasizes the necessity of making research relevant, stating that while 30-70 percent of funding can come from the public sector:"The rest of our financing has to come from the industry itself and they need to find our project interesting in order to invest. The system is therefore set up for research to be relevant."

IRIS functions as one of the connection points for the public and private sectors, establishing a link between diverse international research bodies from NASA, which is looking to adapt Norwegian drilling technologies for use on Mars, to other Norwegian clusters, the University of Stavanger and the private sector.

Carbon Capture Storage in the Valley of Death

The value of long-term public funding in the area of research and development is clearly evident in the story of carbon capture storage (CCS). Bjorn-Erik Haugan of Norway's publicly funded CCS-focused research institute Gassnova explained:

"Going back just over two or three years, there where huge expectations being placed on CCS technology in terms of how fast it might contribute to combat global warming. Reality has now set in, in the sense that a lot of the projects for the development of CCS technology have not materialized at the pace that people expected. We are now in what others might refer to as the "valley of death" in CCS innovation."

Haugan said that the popular mandate for exploring this type of technology had subsided with climate change being taken off the agenda, and a carbon market has not emerged. Even Germany has bowed down to popular misconceptions.

"Germany has practically banned the storage of CO2 because the government has bowed to popular but erroneous belief. This has led to the situation where they are quite happy to accept the storage of natural gas under their football stadium in Berlin – which is a gas that can potentially explode. However, they do not accept the storage of a perfectly inert gas in their country."

Though, as Haugan puts it, the naysayers currently have the upper hand, Norway's steadfast publicly funded commitment to this technology and the recent opening of the new Technology Center in Mongstad. "Norway could end up playing a crucial role in reversing the swing."

| The next issue in our series of reports on Norway will be published in a late summer edition of Oil & Gas Financial Journal |