Where does bribery legislation bite?

ABC legislation exists across many jurisdictions, but enforcement varies dramatically, prompting companies to 'enforce' measures themselves.

Toby Duthie

Forensic Risk Alliance, London

Derek Patterson

Forensic Risk Alliance, London

David Lorello

Covington & Burling LLP, London

Anti-bribery and corruption (ABC) legislation is similar across many jurisdictions. The prohibitions are deliberately broad and typically follow standards set forth in the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention*, which in turn was largely modelled on the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA). The US FCPA allows for facilitation or 'grease' payments, however most other ABC laws do not. Indeed we are not aware of any jurisdiction which allows for bribery of its own government employees, even if they might constitute "facilitation payments" under the FCPA. What does change dramatically from jurisdiction to jurisdiction is the level of Government enforcement. This can be summarised as:

- USA - the global leader by quite some distance

- Germany - the European leader

- Canada, UK and Switzerland - the jury is out but enforcement is likely to step up

- Scandinavian jurisdictions - there is emerging interest and a number of high-profile cases against major companies

- Emerging markets - increasing enforcement, although often the enforcement is quite selective (for example in Russia) or the actions represent "carbon copy" enforcements in local jurisdictions following US prosecutions (this trend has been seen in particular in Africa in recent years)

- China - increasingly, the policy is to target low-level bribery as well as major incidences

It is worth noting that the US will, and frequently does, prosecute non-US individuals and corporates – indeed, some of the largest FCPA enforcement actions have been taken against non-US companies, and the US government has extradited foreign nationals to be prosecuted in the United States for FCPA-related misconduct. In view of the aggressive global reach of the US regulators and prosecutors, as well as dramatically increased cross-border co-operation, jurisdictional arbitrage is ill-advised – there is nowhere to hide from the risk of anti-bribery enforcement risk. This is especially true in the oil and gas sector, which is dollar based and typically has a strong US commercial nexus (investors, project sponsors, consumers etc.).

International financial institutions (IFIs) such as the World Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) are also taking an increasing interest in identifying and punishing corruption in projects which they fund (such as, in particular, by pursuing debarment actions against companies that engage in corrupt practices in connection with bank-funded projects). In many ways, dealing with IFIs can be even more difficult than dealing with a national regulator. The IFIs are not bound by national processes or precedent, yet they increasingly set the rules by which corporate activity is judged.

As noted by David Lorello, a partner at the law firm Covington & Burling who has been involved in numerous World Bank corruption cases, "for companies who pursue significant volumes of business through the IFIs, the risk of debarment may present an even more significant risk than the prospect of national prosecution. In contrast to many national authorities, the IFIs are active in investigating and pursuing corruption cases, and the periods of debarment that they impose can extend for many years. Moreover, the debarments apply to business anywhere in the world, and if a company is debarred by one of the major IFIs (such as the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, EBRD, or the Inter-American Development Bank), the other IFIs will often cross-debar the contractor from their projects."

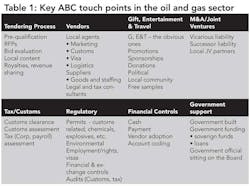

Key ABC touch points in the oil and gas sector exist both at an operational level and in terms of business development (tenders, JVs, M&A). See Table 1.

Privatization of enforcement

What is increasingly apparent is that, especially in oil and gas and mining, companies are increasingly mindful of exposure through acquisition and partnership (formal and informal) as well as through misconduct by counterparties (vendors, distributors, advisers etc.) – respectively known as 'successor' or 'vicarious' liability. Such liability can have significant impact in terms of investigative and penalty costs as well as more consequential costs – such as marketability of assets, access to and cost of capital, reputational damage, management time etc. All of which creates a strong incentive for companies themselves to 'enforce' anti-corruption measures. This private sector 'enforcement' takes a variety of forms.

Given that the number of opportunities in new and established higher risk natural resource markets is growing along with the investors' pursuit of yield, we are seeing the demand for more – and specifically more heightened and ABC-specific – due diligence. This type of due diligence is very different to the typical materiality-driven M&A-related due diligence carried out by commercial lawyers and auditors. ABC due diligence is risk-based and transaction-focused – for example, looking at recent customs-related enforcement cases, small payments have caused major problems and resulted in fines totalling hundreds of millions and operations being shut down in high risk locations (e.g. Panalpina). Conducting effective due diligence on ABC risks also necessitates a clear understanding of the nature of the underlying business and the jurisdictions where the business operates - "one size fits all" ABC due diligence options seldom will produce effective results.

We have also observed that, increasingly, up-front due diligence is being followed up by the implementation of robust operational controls, which again will vary considerably from transaction to transaction:

Audit rights – e.g. vendors, JV partners and local operations, distributors

It is important both to ensure that audit rights are provided for in relevant agreements, and for the company to have a coherent strategy that defines the circumstances where it will actually exercise those rights. Auditing every third party contractor is neither practical nor wise, but it is similarly unproductive to have contractual audit rights in place that are never utilized.

These audits involve detailed reviews of the controls environment within a business partner's operations. This is typically achieved through a combination of risk mapping and judgemental transactional sampling. The intention is to test the adequacy of key policies and also the extent to which these policies are being implemented.

The tolerance level as to historical issues can be weighed up based on legal analysis, commercial risk return assessments and the ability to close out issues and prevent their re-occurrence. In short:

- How big an issue is it and what is the potential exposure – financial and personal?

- What does this mean to our business and how can we manage the exposure?

- Can we make sure it doesn't happen again?

ABC indemnities, representations and undertakings, conditional payment obligations – e.g. Halliburton paid approximately half of KBR's $579 million of Bonny Island-related fines. Many oil and gas transactions take place in higher ABC risk countries and are a fact of business. Investors and project sponsors need to be able to manage and assess ABC risks much as they do other risks – it is critical to do so to ensure early detection and prompt remediation. This means:

- Ideally, pre- and post-investment ABC due diligence

- Strong operational controls backed up by contractual rights

- Effective and timely management Information

Conditional rights to parties in the event of reasonable suspicion of ABC events – e.g. enhanced audit rights, assumption of Board Control.

Drive for 'local content'

Increasingly, countries are pushing for significant 'local content' (use of local workforce, suppliers, etc.) – and rightly so. For example, local legislation might require that there be local shareholders, or a certain number of local employees or the requirement may be less formal: local content levels will factor in tender evaluation procedures, for example. This manifests itself in a variety of contexts, however, and often what appears as an effort to comply with local content requirements is actually an opportunity to generate revenue for government-affiliated individuals.

The challenge in these instances is to ensure that local content requirements are fully understood and not overstated, that the local content provider is adding demonstrable value on an arms-length basis, and that the provider does not have affiliations with government officials in a manner that creates unacceptable ABC risks.

Local content is a positive development but it needs to be carefully and consistently considered. The days of the overly remunerated local marketing agent may be numbered, but the risk remains in new and more subtle forms. Today, for example, it may consist of a local catering provider whose beneficial owner is unknown and who is offering services priced above the norm.

Why does this matter to the investor?

Investment value is directly impacted by poor compliance. Ignoring the obvious risk of regulatory action, it is clear that tainted assets are more deeply discounted or not marketable at all and potentially exposed to heightened expropriation risk. As the risk of anti-corruption enforcement becomes more international, and commercial liabilities arising from ABC risks likewise increase, those issues will only grow in magnitude.

Vendors who potentially expose their customers to risks due to poor ABC controls find themselves ruled out of tenders, which hits their bottom line – companies with strong compliance can pursue higher risk and higher reward opportunities. An interesting variant here is the development of strong interest arising at IFIs such as the World Bank or the EBRD, and their ability to debar companies from bidding on projects for a material period of time, with significant commercial implications. The investigation processes, findings and debarment processes, and appeal rights when dealing with these institutions, are less clear than they are for national regulators.

At its essence, good compliance underpins value and reduces cost of capital. The opposite is equally true. From our experience, a strong controls environment forms part of an overall culture and manifests itself throughout the corporate DNA, whether this be in HSE, budgeting, procurement or ABC compliance. The challenge with ABC risk is that it is not always obvious or material. Risks need to be mapped and tested on an iterative basis and the controls should sit at an operational level. All of this takes up-front investment which, if properly structured, can be cost-effective and then revisited periodically.

About the authors

Toby Duthie is a partner at Forensic Risk Alliance (FRA), is a consulting firm with offices in the US, UK, France and Switzerland that provides independent, conflict-free advice and litigation support services aimed at helping businesses resolve complex and high-risk financial, legal, and regulatory challenges.

David Lorello is a partner in the firm's London office and a member of the Anti-Corruption and International Trade and Finance practice groups. Lorello advises clients concerning a range of international regulatory and commercial matters under both European and US laws.

Derek Patterson is a forensic accountant with over 20 years' experience in reviewing complex financial facts, fraud and corruption, evaluating financial losses, and in matters requiring internal investigation.

*Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions Adopted by the Negotiating Conference on 21 November 1997