Great Expectations

Is there an estimation bias behind exceptionally high discovery rates?

Imre Szilágyi, Exploration geologist and petroleum economist, Budapest, Hungary

Last year the discovery rate of exploration drillings was as high as 65%. We read such projections in annual reports and hear them in management road-shows. What are we to make of these estimates? Do they tempt investors into thinking their money is in good hands as the company seems to be managing exploration risk professionally?

It behooves the wise investor to ask the company's management what their a-priori expectation on the success rate was. The risk management efficiency, in the case of petroleum exploration, can be measured by the systematic comparison of the predictions to the results. The methodology of the estimation bias analyses was made available decades ago. If we are talking about discovery rates, it might be useful to refresh our memories.

It is commonly understood that the discovery rate is the ratio of the successful and the total number of exploratory wells drilled in a certain period of time, i.e. one calendar year. Professional but hair-splitting analysts may ask some very interesting questions. For instance:

- What does the term "successful" mean?

- Were the appraisal wells are "exploratory" or not?

- How does the company account for drillings that started in the previous period and finished in the subsequent one?

Of course the questions above — if they were asked — would more or less be answered by company management. But, in fact, the questions are typically not asked. The consequence is that the very different stories behind the same "65% success rate" proudly announced by two different companies are not clear.

Put bluntly, my analysis shows that a "successful" discovery well means only that the drill bit encountered moveable hydrocarbons at least one of the predicted prospects and that the best estimate of the resources found are thought to be commercially recoverable. Appraisal wells are considered only in case they have been drilled with the clear intention to increase the resource volumes that had been assessed upon the completion of the first discovery well.

As far as the evaluation period is concerned, I recommend not using the calendar year approach but instead suggest the analysis be based on an evaluation of the "business plan portfolio." This means that the evaluation base would be the portfolio of exploratory drillings approved by the management as part of the subsequent year's business plan.

The success rate, under this approach, would be the ratio of the successful and the completed wells — in the business plan portfolio. When the success rate is "announced," one may add the number of pending wells that are uncompleted at the time of the report.

To decide if the success rate, as interpreted above, is "good" or "bad," it should be compared to the prediction that was made. The "prediction" is the probability of geological success — on the level of the business plan portfolio. The Probability of Portfolio Success (hereinafter referred as PPS) is derived from the geological probabilities of the targeted prospects, as it is discussed below.

Assessment of the probability of geological success

The probability of discovering new petroleum pools has been assessed for decades on the basis of geological considerations. Hence it is referred to as Geological Probability, and it is in fact an expert estimation of geoscientists. The Geological Probability (pg) gives the chance that the prospect is a petroleum pool of recoverable resource volumes. If a well targets a single prospect, pg equals the Probability of Geological Success (PoGS) of the drilling project. If the well targets multiple prospects, PoGS is derived from the Geological Probabilities of the targeted prospects, and it gives the chance that the exploratory well will find at least one of them.

The importance of the Geological Probability assessment lies in the role that PoGS plays in the economic analyses of exploration projects. It is the major influential parameter of the Expected Net Present Value (ENPV) taken as the base of financial ranking.

Exploratory wells drilled to new prospects are normally characterized by a PoGS of 20% to 50%, depending on the exploration maturity of the prospected area. It means that our chance of drilling a dry hole is usually more than the probability of success. In case of an appraisal (extension) well targeting an unexplored reservoir unit of an already discovered accumulation, the PoGS might exceed 50%.

The question we face now is how to judge the "correctness" of the Geological Probability assessment. Obviously, the assessment for a single well cannot be "incorrect." If a well with a 25% chance of success proves dry, the company was "unlucky." Conversely, if it is successful, the company simply is "lucky."

The judgment on probability estimation "goodness" might be the same if the company is drilling three wells with an "average" success chance of 25%. If two out of the three were successful, the success rate is 66%, which only proves that the company was lucky. Of course, the management team can be proud of being lucky, but it is no proof of excellence.

The risk diversification efficiency, or in other words the "correctness" of the Geological Probability estimation, can be determined if the company runs a portfolio of exploratory drillings. The portfolio should consist of sufficient number of projects enabling the rules of statistics to apply.

Probability of portfolio success

The term "exploration portfolio" is commonly used for the composition of the company's actual and strategically planned exploration projects where "projects" are contracted and envisaged concession work programs. Without challenging the rationales of this approach, in this study I narrow the definition of exploration portfolio to exploratory drillings for what the management approval has been given. My rationale is that the "correctness" of exploration risk diversification can be analyzed only on the business plan's horizon.

Each exploratory drilling project is characterized by the Probability of Geological Success (PoGS) and the best estimate of the Recoverable Resource Volume (RRV). By the multiplication of RRV with PoGS we can obtain the Risked Recoverable Resource Volume (RRRV). The cumulative of the risked volumes (∑RRRV) gives value what the business plan portfolio "promises" to deliver on an "aggregated" geological probability. This probability is defined as Probability of Portfolio Success (PPS), and is calculated as the ratio of the totals of the risked and unrisked recoverable resource volumes (∑RRRV/∑RRV).

For the exploratory drillings' business plan portfolio, the PPS should describe the success expectation and compare it to the actual success rate of the same portfolio.

Estimation bias analyses

The estimation of geological probabilities is unbiased if the discovery success rate of the drilling portfolio closely matches the PPS. However, the eventual deviation of the two is not necessarily a sign of a bias. It can be the consequence of the fact that the portfolio consists of few projects.

Certain deviation might be acceptable for robust portfolios as well. However, significant and trend-like deviations that prevail for a longer period of time (i.e. for three consecutive portfolios) are clear indications of systematic under- or over-estimation of the geological probabilities.

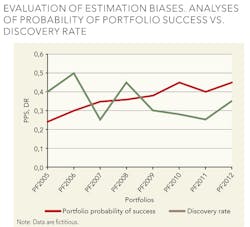

The accompanying graph shows the geological probability estimation bias analyses diagram for eight consecutive business plan portfolios of a fictitious company. The diagram suggests that geoscientists underestimated the geological probabilities for the portfolios of 2005 and 2006 because the Discovery Rate is significantly and repeatedly less than the PPS. For portfolios of 2007, 2008 and 2009, the Discovery Rate fluctuates around PPS, which means that the estimation in this period was basically unbiased.

Management may decide if the measure of the fluctuation is acceptable or not. The PPS, however, proved higher than the DR for the consecutive portfolios of 2010, 2011, and 2012. It is a clear sign of a trend-like overestimation of the geological probabilities.

Company management may ask the exploration department to evaluate the estimation bias. The geoscientist community must properly perform the post-mortem analyses of dry wells to find out if the false assessment of a specific geological probability component (source rock, migration, reservoir, seal, or trap) is attributable to the bias. The analyses may conclude that geologists are too optimistic in general. If lessons are learned and corrective measures are applied, the estimation would return to "normal."

Overestimation is undoubtedly a problem. Is underestimation a problem, too? I think it is. I know from practice that financial managers, especially those convinced of the desperate optimism of geologists, ask geoscientists to give conservative estimations. The consequence can be an undervaluation of the exploration projects, and the result can be that good projects are dropped due to their poor ENPV. I think the estimation of geological probability should be as fair as is the assessment of recoverable resources and financial variables.

Conclusions

Based on the discussion above, one can conclude that an exceptionally high discovery rate neither informs about professional excellence nor proves efficient exploration risk diversification. However, it can be proof of good exploration performance if the discovery rate closely matches the success chance expectations for consecutive business portfolios.

One-off deviation of the predicted and achieved discovery rates may occur as a consequence of luck (good or bad). Once the under- or over-estimation is sustained for a longer period of time, we have good reason to suspect an estimation bias.

Estimation bias can be caught by a systematic analysis. It requires quality data management, expertise, and management commitment for perfection.

About the author

Imre Szilágyi is an independent exploration geologist and petroleum economist based in Budapest, Hungary. Having gained industry experiences as senior and line manager with a mid-size operator, he is currently running a private exploration business consultancy. As part of his management research, Szilágyi recently completed a study on the methodology of geological probability estimation bias analysis. He holds an MS degree in geology from Eötvös Loránd University and an MBA from Budapest University of Technology and Economics. Szilágyi can be reached at [email protected].