LNG projects' cost, competition analyzed in new study

A recent analysis of LNG projects' costs and their costs of service (COS) indicates that, despite low energy prices, most expansion projects and several grassroots projects are economic under conservative pricing scenarios.

The study of LNG cost and competition by Poten & Partners Inc., New York, and Merlin Associates, Houston, addresses how a set of new LNG projects competes in prospective markets. The study estimates costs and cost-of-service for recent and prospective LNG projects to assess:

- Which prospective LNG projects will be economically viable at expected prices? Can current pricing structures support required new supply? Could the current price structure be challenged in a sellers' market?

- How are prospective LNG projects positioned economically to compete with each other for sales into current and emerging LNG import markets?

- How do projects compare in the key components that make up each project's COS: FOB technical costs, sovereign take, condensate and LPG co-product credits, and shipping?

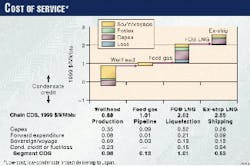

The study says that a project's COS is the minimum price it can charge to cover outlays and earn an acceptable rate of return.

It defines COS as the real levelized price (1999 $/MMbtu) per unit of LNG or gas output covering forward capital and operating costs; sovereign take; recovery of capital employed at start-up, including a required after-tax rate-of-return (ROR) or "hurdle rate"; and net of condensate and LPG co-production credits.

The study calculates COS for each segment of the LNG chain (production, pipeline, liquefaction, and shipping), and within each segment, for each outlay.

Flood of projects

Since 1990, even with low energy prices, there has been a flood of committed and potential new LNG export projects, says the study.

In Asia-Pacific, new projects amounting to 25 million tonnes/year (tpy) have come onstream since 1990. At least eight prospective expansion and greenfield projects in Southeast Asia (including Australasia) and the Middle East are actively looking for markets, for about 50 million tpy. Another three projects, more costly or less advanced, are under consideration.

In the Atlantic basin, Algerian refurbishment has added 8 million tpy, two new projects bring 9 million tpy to market in 1999 year with 12 million tpy of expansion sales in prospect, and at least three new projects are under consideration.

Not since the high-energy-price era of 1977-1983 has the LNG business seen such activity, says the study.

Methodology

The Poten & Partners-Merlin Associates study contains two elements: assessment of costs and COS. Both have been estimated for recent and prospective LNG projects (named and discussed in detail in the report which the companies sell).

Engineering-based costs for export projects by segment (production, pipeline, and liquefaction) are derived from a specific basis of design for feed-gas production, pipeline transportation, liquefaction, storage and marine requirements.

The basis of design accommodates feed-gas quality and gas liquids co-production. Cost estimates are derived from a comprehensive database for actual and proposed projects over the last decade.

The database supports the derivation for each project of a bill of materials whose costs are estimated at current market conditions and incorporates specification of local labor wages and productivity. Costs for ships and ship operations are based on current experience.

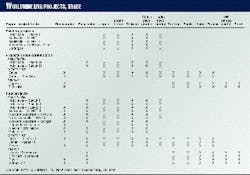

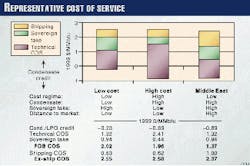

Table 1 gives an example of the design bases and costs for generic low-cost and high-cost projects.

The COS methodology employed in the study incorporates cost and cost escalation, volume and revenue generation, and sovereign take in a cash-flow analysis for each segment in the LNG supply chain. These are integrated to represent the LNG supply chain from the wellhead to delivery. Business structure, transfer prices, risk allocation, and required segment rates of return are consistently represented.

From a capital budgeting perspective, if the project COS is less than the levelized market price, the project net present value (NPV) is positive and the project internal rate-of-return (IRR) is higher than the hurdle rate. Conversely, if COS is higher than price, the project NPV is negative and the project IRR does not meet the hurdle rate.

Thus, other things being equal (which often are not), projects with relatively low delivered COS will be more easily funded, more easily accommodate buyers needs for timing, buildup, flexibility, and security, and be more attractive to host governments.

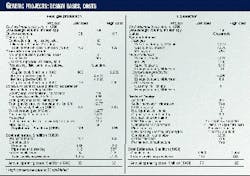

Table 2 gives the key assumptions used in the COS analysis.

Under these assumptions and the costs developed previously, Fig. 1 shows the buildup of COS elements by segment for a low-cost, low-condensate project delivering into Japan. A fiscal regime typical of Southeast Asian projects is specified.

Fig. 2 compares three very different kinds of projects:

- A low-cost, low-condensate project with high sovereign take and a short distance to market. These conditions would characterize a low-condensate, grassroots project in Southeast Asia.

- A high-cost, high-condensate project with low sovereign take and a short distance to market. These conditions would characterize a high-condensate, grassroots project in Australia.

- A low-cost, high-condensate project with sovereign-owned feed gas and a long distance to market. These conditions would characterize a high-condensate, grassroots project in the Middle East.

Interestingly, says the study, these very different projects show roughly the same COS at a level that provides for highly viable competition into East Asian markets.

Earning "hurdle rate"

According to the study, a new trade is viable if its ex-ship price or realization meets or exceeds its COS because then the project will earn at least its hurdle rate.

Of course, says the study, other considerations affect the commitment of a new trade. Under a conservative oil price outlook, in Asia-Pacific markets:

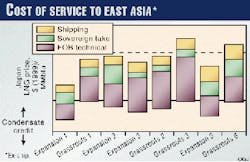

- Five expansion and greenfield projects in Southeast Asia, offering more than 30 million tpy, are economically viable for sales to East Asian buyers under current LNG pricing structures. Middle East expansion projects are viable as well.

Fig. 3 indicates the relationships of ex-ship project COS to anticipated LNG market price for these and more costly projects.

- Projects that commit to sales in the next couple of years will take 3-4 years to construct and a subsequent period to reach plateau volume. The study estimates that uncovered LNG demand in East Asia (current buyers plus China) by about 2007 is approximately 21 million tpy.

Thus East Asian LNG markets see potential supply from Southeast Asian sources exceeding demand in this period.

- If Indian buyers will pay ex-ship prices matching those in current ex-ship LNG sales, Southeast Asian export projects can viably trade to India.

- Middle East expansion projects have FOB COS significantly lower than most Southeast Asian projects, due to expansion economies and gas liquids endowment.

Potentially large LNG demand in India could absorb much of planned Middle East expansion capacity and some Southeast Asian supplies as well. Depending on the volume of Indian purchases, however, aggressive pricing by Middle East projects could control Indian markets and penetrate East Asian markets.

As Fig. 3 shows, projects differ in the composition of the COS due to differences in facility requirement (especially in the upstream), cost of construction, gas quality and condensate endowment, and sovereign take and business structure. Detailed breakout of projects' COS by segment and outlay quantify these differences.

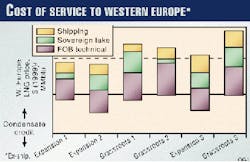

In the Atlantic market (Fig. 4), gas and LNG prices are lower than in the Pacific.

- Expansion sales from Nigeria and Trinidad can trade quite profitably at prospective prices set in current European and US gas markets and are competitive in new Latin American markets.

- Greenfield Atlantic projects and Middle East supplies will be challenged to meet prices in these markets.