SE Asia's refining surplus typifies bad choices in decisions to add capacity

Gale Richards

Sterling Group

Houston

This Management Perspective is the last in a three-part series on consolidation in Asia's refining-marketing sector. This week, a Sterling Group analyst looks at what is needed to resolve the dilemma of surplus capacity in Southeast Asia and how that relates to refiners worldwide.These days, when anything goes wrong in the Pacific Rim, many analysts are quick to condemn the region's economic crisis as the root cause.

So when Southeast Asia started showing a surplus in refining capacity, the court of global opinion reached a swift and succinct verdict: The region's refineries were simply the latest victims of the economic tsunami washing over the entire hemisphere.

Here is another theory: The true culprit behind excess refining capacity is not the economic crisis, but a classic case of exuberant, unfettered overbuilding. Encouraged by government-operated agencies eager to jump-start their economies and fueled by rosy projections of growing consumerism, new and upgraded refineries have sprung up throughout the region.

In just the past 2 years, the boom in new construction moved the region from a net importer of refined products to a net exporter. But when refineries in Singapore and Thailand reduced crude throughput in response to excess product supply, it was clear that overcapacity problems were serious. The economic crisis just made a bad situation worse.

SE Asia capacity

Southeast Asia's refinery capacity has changed markedly in the past decade.Capacity throughout the region has grown at nearly 8%/year since 1990 (see chart, this page). South Korea alone more than doubled its refining capacity-to 2.54 million b/d from 1.244 million b/d-during 1996-98.

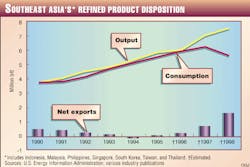

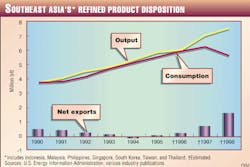

The chart on p. 18 shows the refined product disposition (consumption, production, and net exports) in Southeast Asia and documents the substantial increase in exports during the past year. From 1990 through 1996, Southeast Asia's refined products demand grew by about 8%/year.

In 1997, demand growth dropped to about 5%. Demand growth has been estimated at -10% for full-year 1998.

Oil & Gas Journal's Worldwide Construction Update shows refining capacity additions of about 8%/year through 2002 (OGJ, Oct. 5, 1998, p. 63). The decline in planned capacity additions shown in the 1998 construction update can be attributed to deferred investment. It is a virtual certainty that planned capacity additions for the region will return with a vengeance without any economic data to justify them.

The drivers that promote overbuilding are not unique to Southeast Asia. The disease can strike anywhere. Western Europe and the U.S. always seem to be teetering on the brink of refinery overcapacity, with one or the other-or both-stricken by an overbuilding bug every few years.

Regardless of the country or region it strikes, overbuilding can always be traced to two fundamental causes: intense competition and overly optimistic margin forecasts. Put these two ingredients together, and that ensures more capacity growth. The factors that contribute to this overbuilding are worth examining.

Incremental-barrel economics

Thanks to specifications mandated by governments and end-users, refined products have become standardized commodities, with one gallon of diesel fuel virtually impossible to distinguish from another.The only variable is price-and manufacturers diligently work to win the price war by lowering the unit cost of their commodities. The fastest way to lower unit cost is to boost throughput. On any theoretical production run, the best margins are found on the last barrel to be refined. The allure of this "incremental barrel" leads refiners to boost throughput to reduce unit costs and increase operating margins. Financial officers love incremental capacity because it represents the lowest-cost approach to improving margins.

Understanding this "incremental" perspective helps explain why every refinery operator in the world is always looking for ways to expand or upgrade its facility. In the U.S., this "capacity creep" has been responsible for increases of 0.5%/year in total distillation capacity.1 The downside, of course, is right around the corner. As refiners reduce unit costs by increasing throughput, new supplies flood the market. The game ends badly, with downward pressure on product prices and lower margins for everyone.

Responding to competition

As competition intensifies, the need to lower costs becomes even more compelling.In Southeast Asia, refining and products-marketing have become positively cutthroat as manufacturers scramble to retain market share. The competitive realities will only get worse, thanks to continuing mergers and alliances, increasing foreign investment, privatization, deregulation, and the trend of state oil companies crossing traditional geographical borders. Everywhere one turns in Southeast Asia, refiners face new sources of competition, such as the following:

Underestimated future supply

Even as the economic crisis has reduced demand throughout Southeast Asia, new forecasts are being circulated that predict substantial increases in demand over the near term.Apparently it's not a question of "if" but "when" countries in the region will embark on new refining projects.

The method used for assessing the need for additional refining capacity is almost always the same. To determine future refining capacity, analysts total up the existing refining capacity and typically add only announced refinery projects. This supply forecast is then compared against the projected demand. Every so often, an erstwhile analyst will take the extra step and add "rumored projects" to his or her refining product supply forecast. But common sense should suggest that there are always more projects in the works than are announced or rumored, and few, if any, analyses consider the collective effect of elements such as capacity creep or the industry's ability to alter product or crude slates to accommodate changing product demand. The end result is a chronic underestimation of future refined product supplies.

When refiners see a gap between anticipated supply and demand, they quickly conclude that improved margins are on the horizon-and use the expected windfall to help justify expansions, upgrades, and new grassroots refineries. Predictably, the gap never materializes in the manner in which it was envisioned. History shows that refining margins may rise and fall, but they typically fluctuate only within a small band.

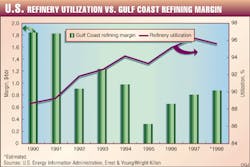

Optimism reigns in the refining industry. When manufacturers believe that demand is outpacing supply, they hope for increased utilization rates and better margins. Refiners in the U.S. have long believed that higher margins will follow increased refinery utilization. This has not occurred. U.S. refinery utilization has increased steadily since 1980 and reached 96% by third quarter 1997. Amid these robust figures, industry margins over the same period trended down, not up (see chart on p. 18).

The illusion of rationalization

When analysts build their economic models, they typically account for plants that might cease operating in the near term, either for lack of willing capital to fund upgrades or because of portfolio rationalizations that follow mergers.Although Southeast Asia's refiners are burdened with significant excess capacity, low margins, declining demand, and, in some cases, high debt levels, economic conditions are expected to prompt few, if any, plant shutdowns.

Historically, rationalizations rarely prompt plant closures, and when they do, they shutter only the facilities known for their small capacity and high costs.

Other potential shutdowns are averted by the high costs of environmental clean-up after a closure, system interdependencies that require even marginal plants to continue operating, and manufacturers' unwillingness to lose an existing customer base.

Fear/hope/survival

Refiners often expand or upgrade their refineries even when the economics fail to justify the investment. One reason is fear. Refiners fear becoming dependent on another supplier for their product and/or they fear missing out on potential margin increases.Refiners that have significant retail marketing are reluctant to lock into long-term supply agreements or rely on undependable spot purchases. Running out of product that is necessary to supply customers can devastate profits, ruin customer relationships, and even spark lawsuits from distributors. Fearing the consequences of doing nothing, refiners instead press ahead with decisions-bad ones, mostly-to upgrade or expand their plants.

Hope is another sentiment that prompts unwarranted investments. Refiners come across data that indicate the potential for higher margins in the future-and they willingly open their corporate wallets and hope for the best. If margins really do wind up higher, the capital investments will pay off. If margins end up low, no one wanted to be locked into a high-cost supply agreement, anyway. The eventual margins may not be enough to return the capital invested, and the new capacity helps ensure that margins throughout the industry do not improve.

It takes about 3 years to initiate, design, and construct new refining capacity. If additional future needs are forecast, refiners have limited options if they want to survive. They can find an economical supply contract they can live with for years (which is very difficult), or they can decide to invest in new facilities several years in advance of anticipated needs. Even if today's forecast margins justify new capacity, there is no guarantee that profitable margins will be waiting when the new plant, or additional capacity, comes on line years down the road.

In fact, because your competitors started building when you did, there should be every expectation that margins will have collapsed by the time your facility is completed. Refinery grand openings in Southeast Asia promise to be very gloomy affairs in the years ahead.

When new capacity is needed

Hyperinflated projections and bad data are a few of the reasons not to build new refining capacity. But a few valid reasons exist to justify upgrades or new construction. They include:- Value chain integration. If a company is fully integrated, it may make sense to have refining capacity as a steady outlet for the company's oil production, or as a guaranteed source of product for the company's retail marketing segment. Sustaining full integration also insulates a company against some of the value-chain margin fluctuations prompted by market forces and government intervention.

- Access to a new or isolated market. Entering a new or isolated market ahead of the competition may provide a competitive advantage by creating barriers to entry.

- Crude transportation cost savings. If a company's crude production is not near a refining center, transportation savings could justify new refining capacity.

- Building relationships. Some countries will not allow foreign firms to initiate or operate retail marketing without investing in refining capacity.

- Feedstock for petrochemicals. Al- though the petrochemical industry is currently experiencing overcapacity, it may become economical for refiners to produce their own petrochemical feedstocks.

The best recommendation is really quite simple: If an analyst delivers a report calling for new plant capacity, a refiner should ask for supporting data. If all that entails are feeble forecasts of higher refining margins due to future inadequate supply, the decision should be one of the easiest a refiner ever made.

References

- Oil & Gas Journal, Mar. 24, 1997, p. 24.

- SBC Warburg report, Philippines, Petron Corp., Apr. 29, 1997.

- EIA Country Analysis Brief, Philippines, June 1998.

- Daiwa, Korea Equity Research, Oil Refining Sector, Aug. 22, 1997.

The Author

Gale F. Richards is a project manager with Sterling Consulting Group in Houston. She has been engaged in the oil and gas industry for over 18 years, covering all aspects from refining operations and retail marketing to long-term strategic planning. Areas of expertise include refining and marketing studies, competitive intelligence analyses, strategic planning, and financial analyses of actual and potential acquisitions, divestitures, and business alliances. Responsibilities have included team management, project management, meeting facilitation, economic modeling, refinery process engineering, marketing studies, pipeline feasibility studies, and various business analyses. Prior to joining Sterling in 1998, Richards worked, in reverse order, for Ernst & Young/Wright Killen as a manager, Micronomics Inc. as research director, ARCO Products Co. as senior industry analyst, Pacific Refining Co. as senior planning and economics engineer, and Unocal Corp. as a planning and process engineer. She has a BS in chemical engineering from the University of Washington, and an MBA from the University of California at Berkeley.

Copyright 1999 Oil & Gas Journal. All Rights Reserved.