US DOE details Marcellus-Utica ethane, petrochemical options

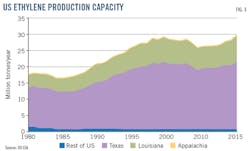

Expanding the US petrochemical asset base beyond the Gulf Coast, where almost all US ethylene production is sited, would enhance its geographic diversity and support reliability of the petrochemical industry. More than 95% of US ethylene production capacity is in Texas or Louisiana. Further, the development of new petrochemical capacity elsewhere would not necessarily conflict with continued Gulf Coast expansion. New capacity beyond the Gulf Coast could serve regional demand for NGL derivatives, freeing up Gulf Coast production for other markets, including exports.

The US Department of Energy (DOE) prepared a report to Congress in November 2018 titled “Ethane Storage and Distribution Hub in the United States.” It addressed the feasibility of a new ethane storage and distribution hub in the US.1 Large hubs for NGL storage, including ethane, are already in place in the US, but the boom in crude oil and natural gas production from shale formations may present opportunities for industry to establish additional hubs.

DOE gathered and analyzed information regarding ethane supply and related infrastructure. This analysis considered projected trends in ethane production over the coming decades, where changes in ethane production are projected to occur, the location and capacity of established ethane storage hubs in North America, and NGL pipelines, among other things. The analysis focused on identifying regions in which significant growth in ethane production is projected and established ethane hubs do not exist.

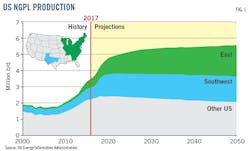

In its “Annual Energy Outlook 2018 (AEO 2018),” the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) projected natural gas plant liquids (NGPL) production to nearly double between 2017 and 2050 (Fig. 1), supported by an increase in global petrochemical demand.2 Most NGPL production growth in the report’s reference case occurs before 2025 when increased demand spurs higher ethane recovery and producers focus on NGL-rich plays.

The large increase in NGL will come from the Marcellus and Utica plays in the east and from the Permian basin in the southwest over the next 10 years. By 2050 the east and southwest regions account for more than 60% of total US NGL production in the AEO 2018 reference case.3

Between early 2011 and mid-2013, industry announced capacity expansions, feedstock changes, and new plant construction because of the significant increase in availability of ethane in the US.4 These investments focused near the Mont Belvieu, Tex., NGL hub on the Gulf Coast and near the hub in Sarnia, Ont. Construction of three new ethylene crackers on the Texas Gulf Coast was completed end-2017. Additional pipeline and export infrastructure was built to export ethane by tanker from terminals at Morgan’s Point, Tex., and Marcus Hook, Pa.; both sites opened in 2016.5

Lacking storage in the east, several pipelines have been built to deliver NGL from the east region to Mont Belvieu and Sarnia; the first pipeline to enter service that moves ethane out of the Appalachia region to Canada was Sunoco Logistics’ Mariner West pipeline, which was commissioned in December 2013. Early in 2014, the Appalachia-Texas-Express (ATEX) pipeline began shipments of ethane from the Appalachian region into the Midwest and Gulf Coast.

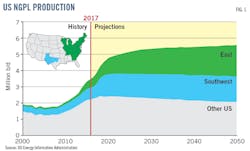

Projected growth in NGPL production in the east region presents an opportunity for industry to establish an ethane storage and distribution hub near Marcellus and Utica shale production. Ethane production in the region is projected to continue its rapid growth. Projected 2025 production of 640,000 b/d, is more than 20 times the regional ethane production in 2013 (Fig. 2). By 2050, ethane production in the region is projected to reach 950,000 b/d.

North America has the second largest ethylene production capacity in the world behind the Asia-Pacific region. Production, however, is highly concentrated on the US Gulf Coast; more than 95% of US ethylene capacity is in either Texas or Louisiana (Fig. 3).

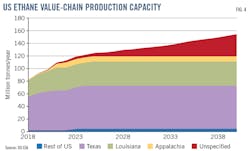

Significant production capacity growth is projected across the ethane value chain, which includes intermediate products such as polyethylene, ethylene oxide, ethylene dichloride, and others. Fig. 4 shows projected capacity growth by region in the US; between 2018 and 2040, production capacity of ethylene and intermediate petrochemical products is expected to increase by more than 85%. The unspecified capacity depicted in Fig. 4 represents projected new capacity that has not been attached to a specific location to date.

The required investments to build a petrochemical hub are significant. For example, a new 125,000 b/d NGL fractionator and related infrastructure (including additional storage capacity) in Mont Belvieu announced by Oneok Inc. is reported to cost $575 million. Shell Chemicals’ ethane cracker project under construction in Pennsylvania is reported to cost $6 billion.6

Natural gas produced in the Appalachian basin tends to contain higher amounts of ethane, and regional processing plants extract most ethane separately to manage pipeline natural gas heat content.7

In support of the dramatic increase in production between 2010 and 2016, natural gas processing capacity in the Marcellus and Utica plays grew nearly tenfold and fractionation capacity increased twentyfold.8

The establishment of an ethane storage and distribution hub near production from the Marcellus and Utica plays could provide supply-diversity benefits to the broader petrochemical and plastics industries. The geographic concentration of petrochemical infrastructure and supply along the Gulf Coast may pose a strategic risk, where severe weather events limit the availability of key feedstocks. Petrochemical expansion beyond the Gulf Coast would increase geographic diversity. This geographic diversity could provide manufacturers with flexibility and redundancy regarding where they purchase their feedstock and how it is transported to them. Moreover, this flexibility and redundancy, as well as the overall increase in U.S. feedstock production, could mitigate the potential for any price spikes in petrochemical feedstocks caused by severe weather or other disruptive events in any one region.

Natural gas, NGL production

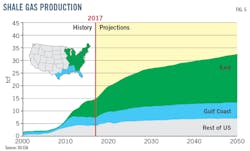

AEO 2018 projects natural gas production from shale resources will more than double by 2050 (Fig. 5). Continued development of the Marcellus and Utica plays is the main driver of growth in total US natural gas production across most cases and the main source of total US dry natural gas production. EIA forecasts production from the Eagle Ford and Haynesville shales to be a secondary source of domestic dry natural gas, with production largely leveling off after 2028. Associated natural gas from tight oil production in the Permian grows strongly through 2050.

The Appalachian basin’s shale resources are such that, were the region an independent country, it would be the world’s third largest producer of natural gas.9 Appalachian natural gas production is projected to continue very steady growth in the short and long-term. Natural gas output, estimated at 8.19 tcf in 2017, is projected to increase by 65% to 13.55 tcf in 2025. Output in 2050 is projected at 19.5 tcf.

AEO 2018’s reference case projects NGPL production to nearly double between 2017 and 2050. Most NGPL production growth occurs before 2025 (Fig. 1), when producers focus on NGL-rich plays and increased demand spurs higher ethane recovery. After 2025, production migrates to areas where NGL yields are lower.

NGPL output in the east region, and by proxy the Appalachian basin, will continue to grow throughout the forecast period. As natural gas production gradually migrates away from liquids-rich gas areas, which are expected to slowly deplete, to dryer areas, the rate of growth in NGPL production will slow relative to the rate of natural gas production growth. NGPL output from 2017 to 2025 will more than double from 610,000 b/d in 2017 to 1.35 million b/d in 2025. NGPL output is projected to reach 1.93 million b/d in 2050.

Ethane production in the region will continue its rapid growth. Projected production in 2025, at 640,000 b/d, is more than 20 times greater than regional ethane production in 2013. By 2050, ethane production in the region is projected to reach 950,000 b/d (Fig. 2), on the back of both higher NGL production in general, and higher recovery of ethane as gas plants improve their capacity to extract a higher proportion of ethane. A world-scale ethane cracker typically consumes around 90,000 b/d of ethane for ethylene production.

Beyond moving ethane from the Appalachia basin to established North American hubs and export markets, the projected growth in NGPL production in the east presents an opportunity for industry to establish an ethane storage and distribution hub near the Marcellus and Utica shales. The extent to which Appalachian NGL will be converted and consumed locally depends on regional infrastructure additions and, more specifically, the interplay between storage and transportation. NGL storage solutions in the Appalachian region are beginning to expand. As storage capacity in the region increases, so too does the potential to use locally produced NGL as petrochemical feedstocks in manufacturing operations expanding and coming online within Appalachia.

Storage

US underground NGL storage sites extend from Kansas to southern Texas and New Mexico. Sites in Mont Belvieu, Conway, Kan., and Sarnia, Ont., all benefit from access to underground salt formations. Mont Belvieu, the largest NGL hub in North America, has more than 240 million bbl of NGL storage capacity. Conway has salt cavern NGL storage capable of holding 21 million bbl. And Sarnia has more than 20 million bbl NGL storage capacity.

The Appalachian region has generally depended on storage elsewhere to satisfy peak-season NGL demand. There are only a few significant regional sites, nearly all of which store propane and are connected to Enterprise Products Partners (EPP) LP’s Texas Eastern Products Pipeline Co. (TEPPCO) pipeline.

Crestwood Midstream Partners’ proposed Finger Lakes NGL storage site at Watkins Glen, NY, was held in regulatory stasis for more than 7 years, first filing a request to convert the depleted salt caverns to hydrocarbon storage in 2009, and satisfying all of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation’s (DEC) requirements by mid-2013.10 The project involved use of two existing caverns on the shore of Lake Seneca at Watkins Glen, near EPP’s Watkins Glen terminal and with a connection to TEPPCO.

As originally proposed, the site would have been capable of holding a combined 2.1 million bbl of propane and butane. Crestwood, seeking support from the adjacent communities, revised the project numerous times, most recently by reducing its scope to storing just propane, and in only the larger, 1.5-million bbl cavern.11 It has also shifted from building the terminal to include rail and truck access, with pipeline access now the only option. In September 2017, one of the last challenges to Crestwood’s DEC application was struck down, allowing the project to possibly proceed.12 But in December 2018 the company said it was no longer pursuing the project.13

Sunoco’s site at Marcus Hook, Pa., sits 300 ft above five granite caverns capable of storing a combined 2 million bbl of NGL and olefins.14 These caverns were mined in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, and were an integral part of operations at its shuttered Marcus Hook refinery. The smallest cavern, at about 200,000 bbl, now belongs to Braskem and is integrated into its polypropylene operations. The remaining capacity belongs to Sunoco with the largest cavern capable of holding roughly 1 million bbl. Some of the capacity is set aside to serve PBP Energy’s Paulsboro, NJ, refinery across the Delaware River, while the rest are part of Sunoco’s operations at the Marcus Hook terminal, including exports.

Sunoco expanded storage at the site as part of developing its Mariner East pipeline. The initial phase of the expansion project, which accompanied the Mariner East pipeline reversal and repurposing for NGL service, included a 300,000-bbl ethane tank and a 500,000-bbl propane tank. Expansion plans include adding a 900,000-bbl propane tank, a 589,000-bbl propane tank, a 575,000-bbl butane tank, and a 300,000-bbl ethane tank.

Energy Storage Ventures LLC, a joint venture between Mountaineer NGL Storage and Powhatan Salt Co., is developing an NGL storage site in Monroe County, Ohio. Phase I of the subterranean storage will operate multiple caverns totaling 2-million bbl, solution-mined in the Salina bedded salt formation roughly 6,500 ft below the Ohio River Valley. The site will serve as centrally-located storage for NGL in the Appalachian region with rail and truck loading capacity as well as two 10-in. OD bi-directional pipelines to Blue Racer Midstream LLC’s nearby Natrium fractionator. Initial storage is scheduled to begin in 2019 and ramp up to full operable capacity by mid-2020. With sufficient interest, the companies may develop Phase II and expand to the site’s permitted 3.25-million bbl capacity.

Appalachia Development Group LLC (ADG) is developing the Appalachia Storage and Trading Hub (ASTH), a proposed underground NGL storage site. The project is intended to be a catalyst for further mid- and downstream development associated with the Marcellus, Utica, and Rogersville shales. To determine its basic eligibility for a federal loan guarantee, ADG submitted a Part I application in September 2017 to the US DOE Loan Program Office (LPO). In January 2018, the LPO invited ADG to submit a Part II application for a loan guarantee under the DOE Title XVII Loan Program, which entails submitting a comprehensive application for the proposed project. ADG is seeking a $1.9-billion loan guarantee that will first require securing an additional $1.4-billion in equity. The site of the proposed hub has yet to be determined. ADG in August 2018 selected Parsons Corp. as its engineering, procurement, and construction partner for ASTH.

The accompanying box details further in-region options for Appalachian NGL storage.

Development

There are three potential paths future infrastructure development could follow, influenced by: global capacity expansion, global demand growth, international aggressiveness in pricing for market share, domestic production trends, capital market preferences, domestic regional incentives, and technological change, among other factors. Underlying each scenario is the general assumption that shale production and the related supply of natural gas and NGL for petrochemical feedstock will continue to grow and that the Marcellus and Utica shales will make major contributions to total domestic supply. The following three scenarios focus on where processing will occur.

In Scenario A, development of a petrochemical cluster in Appalachia is assumed to increase to the point that much incremental Appalachian supply is processed locally. Scenario B assume focus on continued development in the existing Gulf Coast complex. In Scenario C, incremental processing occurs elsewhere, supplied by US feedstock exports.

• Processing in Appalachia. This scenario assumes market participants individually pursue a partial or complete build out of a new petrochemical supply chain in the Appalachian region. The supply chain and the overall size would be smaller and less comprehensive than what is currently in place on the Gulf Coast. Local and regional capital investment would be the largest of the three scenarios.

Required investment to build a petrochemical hub in Appalachia would be significant. Shell Chemicals’ ethane cracker under construction in Pennsylvania is reported to cost $6 billion. New infrastructure would include gathering lines, processing plants, fractionation, NGL storage, ethane crackers, and some combination of plants for polyethylene, ethylene dichloride, ethylene oxide, and other infrastructure. It is likely that without building petrochemical plants that would serve as demand for all components of the NGL stream, some would still be transported out of the region. This would be more likely in the initial years as the petrochemical complex first develops.

Growth in the petrochemical industry would also impact other industries, and additional required supporting infrastructure would be needed. For instance, increased electricity demand could require additional power plant capacity; increased truck traffic could impact existing road infrastructure. These impacts could be mitigated to some degree through coordinated planning and infrastructure development.

New and expanded transportation infrastructure would be especially important to move intermediate or end-use products from Appalachia to markets in the Midwest, Gulf Coast, Canada, or Northeast for consumption or export. These transportation systems would need to be created or expanded. New suppliers and contracts would have to be established.

The required large capital investments highlight the need for coordination across the petrochemical industry since their products are all highly interdependent on feedstock provided by others. Major petrochemical facilities take years to construct, and for the investments to make economic sense, the necessary market demand needs to exist when new plants come online.

Under this scenario, the economic benefit from significant growth in the petrochemical sector would be concentrated in Appalachia through jobs creation and economic multipliers, and this would benefit neighboring markets as well. For example, the Midwest could benefit from lower prices for delivered plastics. Producing and processing ethane in Appalachia using new, more efficient plants and shorter transportation distances to the Midwest than from the Gulf Coast could lower costs and environmental impact. A new Appalachian petrochemical supply area would also be closer to demand in Ontario and Europe.

Adding a new petrochemical supply source would improve the security of supply for markets in the Midwest and potentially across the US. Adding another petrochemical cluster would increase the geographic diversity of petrochemical supply, helping other markets in the event of supply interruptions. Development of an Appalachian cluster is also not necessarily in conflict with Gulf Coast expansion, since Appalachian capacity could serve regional demand for NGL derivatives, freeing up Gulf Coast production for other markets, including export.

• Gulf Coast processing. This scenario assumes a focus on building gathering and gas processing plants to separate and ship purity NGLs rather than building a local petrochemical industry. Increased NGL production would require new pipelines and possible new marine export terminals to be built to take NGL to the Gulf Coast and export markets, and these market opportunities would help expand capacity to handle greater feedstock volumes. Finished petrochemical products (e.g., plastic pellets, etc.) would then either be shipped back to the Appalachian region or exported via the Gulf of Mexico, increasing reliance on using chemical manufacturing at existing industrial centers in the Gulf Coast region.

Scenario B would result in considerably less regional investment in Appalachia. Most initial investment in Appalachia would concentrate on Y-grade (NGL mixed product) pipelines and storage. The new transportation infrastructure would connect to existing infrastructure in the Gulf Coast. Growth of Gulf Coast petrochemical production capacity would ramp up with the new purity product supply, affecting local markets and the labor pool. Economic growth would be split between Appalachian NGL production and processing and Gulf Coast petrochemicals production.

Construction of storage and pipeline infrastructure would provide increased economic activity initially, followed by the gains from increased production. In the Gulf Coast region the increase in NGL supply and associated increase in petrochemical manufacturing capacity would raise economic output and labor employment.

In this scenario, there would be less US security of supply for plastics markets since petrochemical production would remain concentrated on the Gulf Coast. Supply disruptions caused by hurricanes or other factors could impact petrochemical supply chains across the country.

• International processing. Purity NGL products would be shipped from Appalachia for processing elsewhere. This scenario assumes these shipments would be focused internationally to take advantage of existing, but underutilized, petrochemical processing capacity idled due to high feedstock prices and competition from low-cost Middle Eastern petrochemical supplies. New pipelines and marine export terminals would be required to take Appalachian NGL to foreign processing and consumption centers. Export would also allow Appalachian producers and shippers to take advantage of European naphtha crackers now being converted to use ethane as feedstock.

Initial investments would focus on pipelines to move NGL to Canada for plastics production and to East Coast ports for export to Europe. Existing port capacity may be constrained, requiring expansion, which may not be possible at some locations. Ports would likely need upgrades to efficiently handle the expanding flow of NGL. Initial availability of suitable ships meeting port specifications also may be limited.

In this scenario, economic growth would be more distributed, with investment more widely dispersed and smaller than with the buildout of new US petrochemical plants. The export of large volumes of ethane and other NGL would provide economic benefits and positively impact the trade balance.

This scenario increases Appalachian producers’ sales options as it would provide several outlets for their NGL. If one route was constrained or out of service for some reason, the other markets could provide alternatives.

Appalachian potential

Other studies have examined the opportunity for increased petrochemical activity in Appalachia tied to the region’s abundant ethane supply. In March 2018, IHS Markit released a study on the shale region of Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia.15 The study compared a hypothetical investment of almost $3 billion in an ethylene-polyethylene plant in the region versus the US Gulf Coast over a 20-year timeframe. The study points to the access of low-cost ethane and proximity to polyethylene consumption as drivers for financial advantage in the Marcellus-Utica region. Findings of note included:

• The region will supply 37% of US natural gas production by 2040.

• Base case, and using a 15% discount rate, the analysis predicted a net present value (NPV) in 2020 on earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization of $930 million over the life of the project compared to $217 million for a similar Gulf Coast project.

• Under a stress test that included higher capital costs and lower operating rates, a Marcellus-Utica project resulted in negative NPV returns in only 1% of 10,000 simulations.

• Expected returns for a project in the region versus the Gulf Coast are higher under all analyzed scenarios.

The synopsis of the study closes with the statement: “The comparative financial advantage for a [Marcellus-Utica] project would be further enhanced if more-than-anticipated transportation facilities, natural gas and NGL storage, and pipeline infrastructure occurs in the region.”10

Industry has made significant investments in natural gas and NGL infrastructure to support the boom in production in Appalachia over the past decade. Between 2010 and 2016, natural gas processing capacity increased tenfold, and fractionation capacity in the Appalachian region increased from 41,000 b/d in 2010 to nearly 850,000 b/d in 2016 and may grow as high as 1.1 million b/d in 2019. Underground storage projects are being considered, and a world-scale ethane cracker is already under construction in Pennsylvania.

NGL storage is necessary for a future hub since produced volumes typically exceed pipeline takeaway capacity and processing capacity. Storage helps mitigate production volatility and in turn reduces risk for end users.

Appalachia’s abundant resources coupled with extensive downstream industrial activity may offer a competitive advantage that could enable the region to displace marginal producers and help the US gain global petrochemical market share. Nearly one-third of US petrochemical activity occurs within 300 miles of Pittsburgh, with over $300 billion of net revenue. US petrochemical manufacturing capacity and growth is poised to continue expanding given the expectation of shale production growth. Projected, but unspecified to a particular region, incremental petrochemical capacity will generate nearly $227 billion in revenue between 2018 and 2040.

References

1. US Congress, House of Representatives, Committee on Appropriations, “Energy and Water Development Appropriations Bill,” 2017, 114th Congress, 2nd Session, H. Rept. 114-532.

2. US Energy Information Administration (EIA), “Annual Energy Outlook 2018,” 2018.

3. EIA, “Natural Gas Weekly Update,” Mar. 1, 2018.

4. EIA, “Growing US HGL production spurs petrochemical industry investment,” Jan. 29, 2015.

5. EIA, “US ethane consumption, exports to increase as new petrochemical plants come online,” Feb. 20, 2018.

6. Marcellus Drilling News, “Shell Taps Brit to Run the $6B Ethane Cracker Project in Monaca,” Nov. 8, 2017.

7. EIA, “Appalachian natural gas processing capacity key to increasing natural gas, NGPL production,” Aug. 29, 2017.

8. EIA, “Newly released heat content data allow for state-to-state natural gas comparisons,” Oct. 14, 2014.

9. Deloitte Development LLC, “Sustaining Growth: Appalachia’s Natural Gas Opportunity, 2017, p. 4.

10. State of New York, Department of Environmental Conservation, “Finger Lakes LPG Storage LLC, Underground Storage Facility,” October 2014.

11. Smalley, M., “Crestwood adjust Finger Lakes storage facility plans,” LPGas, Aug. 10, 2016.

12. State of New York, DEC, “Ruling of the Chief Administrative Law Judges on Issues and Party Status in the Matter of the Application for an Underground Storage of Gas Permit Pursuant to Environmental Conservation Law Article 23, Title 13 by Finger Lakes LPG Storage LLC,” Sept. 8, 2017.

13. ICIS News, “US Crestwood no longer pursuing underground NGL storage in New York,” Dec. 4, 2018.

14. Montgomery, J., “Sunoco spending $2.5 billion for Marcus Hook operation,” The New Journal, Nov. 6, 2017.

15. Whitfield, R., “The Shale Crescent USA Region” executive summary, IHS Markit, March 2018.

Adapted from US Department of Energy Report to Congress, “Ethane Storage and Distribution Hub in the United States,” November 2018.

Prospective Marcellus-Utica subsurface NGL storage sites

In August 2017, the Appalachian Oil and Natural Gas Consortium (AONGRC) released a geologic study that looked at and mapped potential underground storage options for NGLs produced in the Marcellus and Utica shale plays.

This study evaluated prospective geologic formations in West Virginia, Ohio, and Pennsylvania that offered subsurface conditions eligible for hosting underground NGL storage, prerequisite for an ethane storage and distribution hub and potential growth of the petrochemical industry in the region. Specifically, the following three subsurface storage prospects were investigated and found suitable for prospective underground storage:

• The Northern Prospect encompasses the northern panhandle of West Virginia and adjacent portions of eastern Ohio and western Pennsylvania, presenting storage opportunities in the Clinton-Medina sandstones of Ohio’s Ravenna-Best Consolidated field and two Salina F4 salt cavern opportunities straddling the Ohio River. In addition, the Oriskany sandstone occurs throughout this portion of the Appalachian basin, overlying both intervals, and offers a potential stacked opportunity based on available subsurface data.

• The Central Prospect includes portions of southeastern Ohio, southwestern Pennsylvania, and north-central West Virginia and contains five storage opportunities: Greenbrier limestone mined-rock cavern options; depleted gas reservoirs in the Keener-to-Berea interval in and between the Maple-Wadestown and Condit-Ragtown fields; a depleted gas reservoir in the Upper Devonian Venango group in the Racket-Newberne (Sinking Creek) gas storage field; depleted gas reservoirs in Upper Devonian sandstones in the Weston-Jane Lew field; and a Salina F4 Salt opportunity near Ben’s Run in West Virginia.

• The Southern Prospect is situated in the Kanawha River Valley of West Virginia and comprises the most storage opportunities of any prospect evaluated in the AONGRC study, including mined-rock caverns in the Greenbrier interval; an Oriskany sandstone natural gas storage field; and various depleted gas fields in the Keener-to-Berea, Oriskany sandstone, and Newburg sandstone intervals. What’s more, many stacked and adjacent opportunities are available within a relatively small geographic area. The number, variety and stacking of storage opportunities in the Southern Prospect shows its potential to support a thriving petrochemical industry, according to the study.

AONGRC operates from the West Virginia University (WVU) Energy Institute and is a partnership among two WVU departments and the state geological surveys of West Virginia, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Kentucky.