Growth, environmental issues cloud Asian downstream picture

The Asian energy industry faces a decade with conflicting requirements.

Rapid growth in overall demand for products implies medium-term expansion of refining capacity and perhaps changes in trading patterns. A patchwork of evolving clean-fuels initiatives in various Asian nations will challenge not only the ability of refiners to manufacture fuels but also the flexibility of shipping fuels from one nation to another.

The even more rapid expansion of the petrochemical industry, historically reliant on naphtha from refineries, may conflict with the mandates for clean fuels and the ability of the Asian refining industry to produce suitable naphtha.

Natural gas holds great potential to resolve Asian shortfalls if technological and economic challenges can be overcome.

Demand-growth challenge

With the Asian financial crisis receding into memory, Asian economic prospects are brightening (Fig. 1).

Key economies in China, Taiwan, and India were not badly damaged by the crisis. The more-sensitive economies in Thailand, Korea, and Singapore are generally rebounding, while some countries remain weak.

The darkest cloud on the economic horizon is the impact of an apparent softening in short-term US growth prospects. Nevertheless, the longer-term Asian economic outlook is bright.

Asian demand for light products will expand rapidly (Fig. 2). Light-product demand growth is closely correlated to economic expansion. Many Asian markets for automotive transportation are far from saturated, providing considerable upside demand potential as consumer income increases.

Gasoline, jet fuel, and diesel will show attractive growth over the coming decade.

Asian demand for residual fuel oil is lagging light products. In Asian markets, residual fuel oil is used in many industrial and power applications that often would be served by cleaner-burning natural gas in the North American or European markets.

Gas is becoming increasingly available to Asian consumers in all major energy-consuming nations through expanding LNG as well as pipeline-gas projects.

As gas is introduced, oil is the fuel most commonly displaced. The power generation sector is particularly attractive for natural gas because of the higher efficiencies available from modern high-temperature gas turbine generating facilities compared with older oil-fired boilers or lower efficiency turbines.

The imbalance in growth rates between light fuels and heavier fuels opens the door to more conversion capacity installations. Conversion projects provide the refining industry the opportunity to meet demand for light transportation fuels without over-producing low-value residual fuel oil components.

At this point, most Asian refineries have some conversion capacity. Many Asian refineries, however, have undersized conversion units. Expansion or additions to these units will continue to be an important feature of Asian refinery investment.

Growing conversion capacity will erode the competitive positions of refineries that are unable or unwilling to upgrade. Residual fuel prices are likely to be low relative to light products, providing incentive for conversion installations but also penalizing those who lag behind.

Most likely there will be some consolidation of refining capacity into fewer but larger and more sophisticated facilities with closure of weak refineries in many Asian nations.

Clean-fuels challenge

Even while Asian product demand is expanding rapidly, Asian nations are adopting environmental fuels programs similar to those found in the US or Europe.

Many of the major cities in Asia have serious air-quality problems caused by rapidly expanding populations and ineffective environmental controls. A major portion of urban Asian air pollution problems originates with automotive emissions.

As Asian economies expand, air-pollution mitigation is an increasingly important policy imperative.

Each Asian government is following its own pace for implementation of clean-fuels programs. Many governments, including Japan and Australia, as well as newly industrializing economies, such as Thailand or Korea, are scheduling implementation of various clean-fuels initiatives through the mid-2000s.

The first phases of clean-fuels programs called for unleaded fuels and perhaps low-sulfur diesel, typically 0.05% sulfur. The second phases of such programs typically call for some versions of reformulated fuels and ultra-low-sulfur diesel.

As a group, Asian nations are adopting less stringent reformulated gasoline specifications than those adopted in the US. Often "status quo" regulations are adopted at the outset with scheduled improvements in the future.

Inevitably such improvements come at a cost to refiners.

Asia's lag between initial implementation of environmental specifications and requirements for advanced reformulated fuels will be less than in the US. By 2010, advanced fuel-quality controls are likely to have been implemented in many major Asian demand centers.

Clean-fuels initiatives will require capital investment in affected refineries. Asian refiners will hope to experience margin increases to offset capital requirements and increased operating costs.

The degree to which such increases materialize will likely vary from country to country depending on such factors as the details of the programs including taxes and tariffs, similarity to available fuels meeting other international specifications, trade balance, and the investment path followed by local refiners.

Advancing clean-fuels programs and their capital requirements are the second impetus to closing marginal Asian refineries. The less sophisticated Asian refineries are already struggling, although 2000 brought needed respite from pitiful margins in 1999.

New capital requirements are likely to cause some weak refineries to close their doors. Casualties are likely to include the less sophisticated refineries owned by international refiners who will devote their capital to more promising facilities.

Petrochemical feedstocks

Naphtha has been the predominant feedstock for Asian olefins (Fig. 3).

LPG typically is too expensive to be competitive as an Asian cracking stock. Ethane is cracked in nations with plentiful pipeline gas such as Malaysia and Thailand but is unavailable in more important northeast Asian markets-China, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan.

The ideal naphtha for olefins manufacturing is high in normal paraffins and low in less attractive iso-paraffins, naphthenes, and aromatics. The chemical characteristics that result in favorable olefin-plant yields correspond to the least attractive naphthas for manufacturing conventional gasoline.

The normal paraffins petrochemical producers most highly value are low-octane stocks. Most commonly Asian refiners have produced light straight-run gasolines for this purpose, reserving heavier naphtha for gasoline or aromatics reforming.

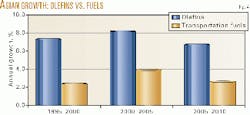

There is a serious imbalance between growth rates for olefins and for transportation fuels (Fig. 4).

High as fuel demand growth has been, olefins growth has been far higher. In most economies, demand for olefin derivatives such as polyolefins or ethylene-oxide derivatives grows at a multiple of GDP growth. Conversely fuels demand, even in most rapidly expanding economies, grows at a rate slower than GDP growth.

The imbalance between these two growth rates presents a long-term problem for petrochemical producers.

The difference in growth rates between fuels demand and ultimately crude throughput, on the one hand, and petrochemical products demand and the requirements for feedstocks, on the other, will result in naphtha representing an ever-increasing fraction of the refinery-output barrel in Asia over the coming decade unless some other feedstock absorbs olefins demand growth.

Expanded NGL production associated with gas developments will mitigate some of the naphtha shortfall. Ethane will be cracked where conditions permit. New condensate production will provide appreciable feedstocks.

Over time, however, the rapid pace of petrochemicals demand growth is likely to outstrip new feedstock availability from this source.

Ultimately most or all refinery light straight-run naphtha could be diverted to petrochemical feedstocks. Light straight-run naphtha can be replaced by fluid catalytic cracker (FCC) gasoline or other converted materials. That situation has evolved in China.

The gasoline quality resulting from such operations, however, is very high in olefins, sulfur, and aromatics. Such fuels have poor environmental emissions characteristics.

Compounding the naphtha problem is the development of reformulated fuels specifications in Asia. Reformulated fuels specifications typically limit olefins and aromatics content. Furthermore, sulfur, benzene, and vapor pressure are reduced.

An important method of meeting reformulated specifications is to retain in the gasoline pool unobjectionable components, which typically are paraffins or naphthenes.

In the US, most of the straight-run naphtha is retained in the gasoline pool and relatively little is consumed for petrochemical purposes. The dilution these components provide is important.

More stringent, reformulated-type Asian gasoline specifications can only increase the importance of retaining high-paraffin stocks, the most attractive olefins feed stocks, in the regional gasoline pool.

Hence, with time, petrochemical feedstock requirements suggest an increasing pressure on refiners to segregate high-paraffin naphtha for sale to olefin crackers, while at the same time environmental fuels specifications will discourage refiners from responding to the petrochemical producers' call.

Refiners also will be under pressure to increase conversion of residual fuel oil components including light vacuum gas oil (VGO) to balance light and heavy product demand.

One method of resolving the imbalances would be to install considerable hydrocracking capacity in Asia to produce high-quality gasoline, adaptable to cleaner burning gasoline specifications. Then light, paraffinic naphtha might be more readily released from the gasoline pool to be converted to olefins in new naphtha crackers.

An alternative method of resolving the imbalance would be to devote heavy components to direct cracking to olefins. While capital and operating costs of VGO-based ethylene crackers would be considerably higher than naphtha-based crackers, more abundant and lower cost feedstocks may overcome the economic hurdle and result in lower cost olefin intermediates.

Olefins cracking would reduce the need for additional refinery conversion. With more light paraffins in the gasoline pool, it might be easier to use less expensive fluidized cracking technologies in lieu of hydrocracking.

New investment

Through the 1990s many proposals were developed for greenfield refinery installations, but the 2000s are likely to see greater emphasis on brownfield expansions. Furthermore, many major oil companies are less enthusiastic about refining than they once were and are reluctant to invest substantial capital in further expansions.

The 1990s saw the installation of major new refineries in many Asian nations. Major greenfield facilities were started up or are under construction in India, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, China, and Taiwan.

As a group, these investments were undertaken with the expectation of very high product-demand growth rates and attractive refining margins. Furthermore, some nations have had slightly different tariff rates on crude oil and refined products that encouraged domestic refining and provided some additional margin cushion.

While on the whole product demand growth has remained high, refinery margins have not materialized as many project sponsors anticipated.

Several factors have contributed to the margin difficulties:

- Many sponsors had unreasonable margin expectations at the outset.

The 1990s were characterized in part by an "Asian fever" that was based on the unreasonable expectation that economic and demand growth was so great that the market would simply be too good to miss. Many investors deceived themselves with margin expectations that were so high that disappointment was unavoidable.

- Tariff barriers have diminished.

The refining industry has not been exempt from the trend toward fewer tariff barriers favoring local production. While some of these barriers remain in Asian markets, they are fewer and lower and no longer provide as much incentive for local refining as they once did.

- Local markets were overbuilt.

The financial crisis hit demand growth in some markets. Refining capacity additions that were based on fulfilling future demand growth became exposed to failure of that growth to materialize.

Product-importing nations became net exporters as new capacity came on line and prevailing product prices at the wholesale level found a new alignment with prevailing market prices in such conditions.

- Brownfield expansions absorbed demand requirements.

Existing refineries in many locations found less expensive expansion opportunities compared with new greenfield refineries. Major brownfield capacity increases were observed particularly in Korea and China with less striking but nevertheless still important additions elsewhere.

As we emerge from the Asian financial crisis, it is more clear to market participants that demand growth is not itself guaranteed and furthermore that it carries no guarantee of margins adequate to support costly greenfield refinery projects.

Both equity and debt investors are likely to be more careful in the future to ensure their projects are justified by market conditions. Most likely there will be new greenfield projects and, we hope, some profitable ones but there will be greater emphasis on the prospects for brownfield expansion as the means to meet market requirements.

Influence of natural gas

Natural gas competes with petroleum in Asian markets, and gas developments will influence petroleum markets in several key ways.

Asia has access to plentiful gas reserves but most are inconveniently located. Major areas of under-utilized gas reserves include offshore Australia, Indonesia, and the Middle East. None of these gas reserves has reasonable prospects for access to traditional pipeline-gas markets commensurate to the scale of the known reserves.

LNG is expanding but faces some new challenges of its own and the most optimistic expectations for the pace of expansion are inadequate to absorb available reserves in a reasonable time.

On the supply side, one key issue is monetizing gas reserves in a reasonable period of time. There is such a volume of gas reserves awaiting development that some companies are holding reserves that would wait decades under the normal course of business before they are developed.

The net present value to these companies of those reserves is very small because of the long period of time awaiting development.

On the demand side, the issue is how to integrate gas into consuming nations' energy supplies. The twin goals of energy-market deregulation for purposes of greater efficiency and of higher gas utilization for purposes of environmental improvement and energy diversity are sometimes in conflict.

For aggressive gas producers, every opportunity to monetize gas must be evaluated. There are myriad alternatives, some based on old technology and some taking advantage of newer developments.

Gas-to-liquids (GTL) technology holds the promise of producing high-quality hydrocarbon liquids. GTL products typically are attractive for producing the most exacting environmental fuels specifications, and hence such projects benefit from the trend toward cleaner-burning fuels.

In most cases, GTL products are likely to supplement clean-fuel supplies from refineries.

Gas-to-chemicals (GTC) technologies may provide higher value-added end products than GTL although the technologies are less developed. As described previously, the demand for olefin-based petrochemicals is growing at a multiple of the rate for fuels products.

Furthermore these chemicals carry higher prices than fuels, and GTC may open the door to a higher netback value for gas even while helping resolve feedstock shortfall issues for refiners and the petrochemical producers.

Notwithstanding prospects for gas development using promising new technologies, the greatest influence gas will have on refiners is grounded mostly in the interfuel competition between gas and oil in the power and industrial sectors.

Pipeline and LNG penetration in India and China in particular but also new consumption in the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and elsewhere will displace oil, mostly residual fuel oil, and exert noticeable influence on petroleum-product demand patterns and refinery investments.

Margin outlook

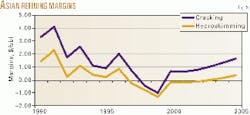

Asian refining margins have followed a generally downward trend since the highs in 1990-1991 attributable to the Gulf War. Even during the brightest period of Asian expansion in the mid-1990s, refining margins were far below those peaks.

Asian refining margins were abysmal in 1999. In 1997 when the financial crisis hit, many Asian refinery projects had recently been installed or were under construction. Demand growth all but halted while capacity increased leading to oversupply in several formerly importing countries.

Some capacity increases still are coming on line, and while demand growth has returned, increasing capacity will dampen margin recovery for the short-term future.

Over the medium term, margins should improve (Fig. 5). At this point, few new expansion projects are being implemented and a cycle of growing imports is adding to prospects for refining margins.

Hydroskimming margins will not recover to historical levels.

Hydroskimming capacity once was more important to market supply than it will be in the future. As residual fuel oil demand erodes compared with other products, simple configurations like hydroskimming will experience margin pressure in exposed, international pricing situations.

Hydroskimming profitability will not be sustainable at levels so poor as to trigger wholesale closure of hydroskimming capacity, but neither will such capacity experience reinvestment economics in most countries.

Cracking configurations will become market setting over time in Asia. In the medium-term future, incremental investments in cracking capacity to upgrade existing hydroskimming capacity will have returns adequate to attract investment.

Over the short term, the market conditions that triggered the 2000 Asian margin recovery-high crude prices, severely backwardated markets, low international inventories, and unanticipated outages at key refineries-are unlikely to be repeated.

More likely, margins will soften in 2001 compared with 2000 until new capacity is absorbed toward 2005.

The author

John H. Vautrain is a vice-president and director of Purvin & Gertz Inc. and heads the firm's Asia-Pacific energy practice from Singapore. His areas of expertise include petroleum, natural gas, and petrochemical feedstocks. Vautrain holds a bachelor's in chemistry from the University of Texas and a master of engineering in chemical engineering from University of Utah, Salt Lake City.