Pakistan's downstream oil sector preparing for deregulation

Pakistan is moving towards significant energy market changes as its downstream oil sector enters a new world of price deregulation. And the country's oil refiners and marketers are being utilized to help bring efficiency to the process.

Economic growth in Pakistan has been turbulent at times, but there has been a consistent increase in the consumption of petroleum products. On the whole, consumption grew at an average of more than 9%/year in the 1980s and almost 6%/year through the 1990s.

Energy demand

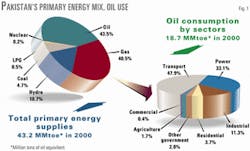

Most of Pakistan's energy comes from oil and gas (Fig. 1), and its use has grown at an average of 4.6%/year and 5.2%/year, respectively, over the last 5 years. This exceeds the overall growth in total primary energy of 3.5%/year over the same period.

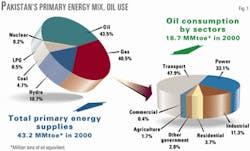

More than 80% of the oil consumed is in the transport and power sectors, both of which have grown considerably (Fig. 2).

In the last 20 years, fuel oil has been the major driver for petroleum product demand; in the future, however, its consumption depends on the pace of substitution by natural gas in power generation. This growth in de mand was not supplemented by increases in refining capacity, and the import bill for petroleum products has risen to an undesirable high of $2 billion/year in recent years. The new Pak-Arab (PARCO) 100,000-b/d refinery commissioned last year will partially and temporarily ease the import situation.

Government regulation

In the past, the government regulated all aspects of the downstream business in Pakistan. The old system was marred with inefficiencies, which provided little incentive for the oil marketing companies (OMCs) and their dealers to operate efficiently and supply quality products.

The price structure of petroleum products was closely regulated, with taxes and subsidies maintaining uniform prices throughout the country. This is being changed, however, as the government has embarked on a process to carry out deregulation of the downstream oil sector.

Deregulating prices and revising margins are already under way. State-run oil company Pakistan State Oil has been privatized, and an independent body, the Petroleum Regulatory Authority, will oversee both upstream and downstream petroleum business in the country.

Product demand forecast

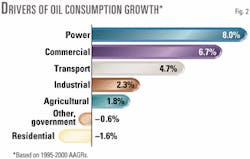

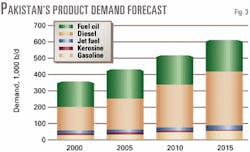

The overall demand of petroleum products in Pakistan should grow 3-4%/year in the 2001-15 period. This demand will grow at almost 4%/year up to 2005, then taper off in the subsequent years.

These estimates assume a real gross domestic product growth rate averaging 4%/year.

The transport sector (gasoline and diesel) has been the biggest consumer of oil products, growing at 4.7%/year. It will maintain its role in the future, driving the growth of oil products con sumption. Gasoline consumption will grow at 4.6%/year from 2001 to 2015, and diesel consumption will grow about 5.5%/year in the same period (Fig. 3).

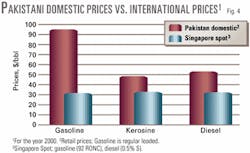

There are several factors that must be considered in forecasting diesel and gasoline consumption. First, the current domestic price of diesel in the country is significantly lower than that of gasoline, which is heavily taxed.

This has led to a distorted consumption pattern, biased in favor of diesel. In the future, however, if the downstream oil sector undergoes full-fledged deregulation, domestic prices in Pakistan might align with international prices. Therefore, this differential would be reduced (Fig. 4), making diesel relatively less preferable to gasoline.

Diesel is not the only substitute for gasoline-the high domestic price of gasoline has made compressed natural gas a viable alternative for motor vehicles.

Although CNG use is currently limited, it will grow rapidly, especially since the government has been actively promoting its substitution for gasoline.

CNG is environmentally friendly, and its use will ease the burden of importing oil products.

Furthermore, diesel-price increases are restricted because kerosine is heavily subsidized. A high price differential between kerosine and diesel will increase the incentive to adulterate kerosine into diesel, which is already occurring (Fig. 4).

Both diesel and kerosine are considered the "poor-man's fuels" in Pakistan, whereas gasoline is considered a "luxury commodity." Diesel mostly is used in public transport. Kerosine is used for cooking, heating, and lighting in low-income rural areas which are not linked to the country's gas and electricity network. Kerosine consumption will decrease as urbanization increases in the country.

Fuel oil is used for power generation in Pakistan, and its use has grown at 10%/year over the last 10 years, primarily because of the increase in the number of thermal independent power producers during this period.

Fuel oil now generates almost 40% of Pakistan's electricity. This is the result of a 1998 decision to use fuel oil for thermal power plants at a time when the price of oil was relatively low. Since then, however, an increase in oil prices has made this heavy dependence undesirable, as it translates into huge import bills.

Now, the government wants to substitute natural gas for fuel oil in power generation. The fuel oil forecast, therefore, takes this factor into account. We estimate that a real GDP growth of 4%/year warrants a growth in power generation of 5%/year. With a moderate pace of substitution, fuel oil consumption will grow 1-2%/year until 2015.

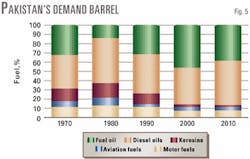

The changing role of fuel oil in power generation has resulted in a changing demand barrel over 30 years. And this will continue, as the current share of fuel oil in total demand will decline in the future (Fig. 5).

Refining capacity; future balance

Pakistan's refining capacity increased significantly with the commissioning of the PARCO refinery last year.

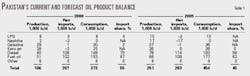

This long-awaited addition in refining capacity has brought somewhat of a temporary relief in the import situation. A demand increase of more than 4%/year over the next 5 years brings about an increase of only 1%/year in the same time period, owing to an output increase of 8.6%/year (Table 1).

This addition is by no means sufficient because Pakistan will continue to import about 60% of its diesel and fuel oil through 2005 and has been planning for new refinery projects accordingly.

One such project is a joint venture with Iran to build a 120,000-b/d refinery. If the project materializes, construction will commence in 2003, and the refinery will start operation by the end of 2005. The refinery would process heavy Iranian crude, and the diesel produced would be used in Pakistan. Unleaded gasoline would be exported to Iran.

Refinery planners in Pakistan need to consider the fact that, although the country can absorb incremental output of fuel oil and diesel, there is currently a surplus of gasoline. Markets outside Pakistan will need to be identified for selling the surplus.

Pakistan now exports gasoline at a rate of 100,000 tons/year.

On a regional context, Asia-Pacific as a whole has experienced a significant increase in its refining capacity. Conse quently, from 1995 to recent years, the region's net imports of gasoline and middle distillates have decreased. Indeed in the recent past, the region has become a net gasoline exporter.

This implies that new refiners in the Asia-Pacific region will face increased competition for export markets.

For now, the government allows the OMCs to import diesel on their own, which is a significant step towards deregulation. Oil imports into the country had been the government's responsibility.

This year, about 70% of the diesel imported will be furnished by a term contract with the Kuwait Petroleum Corp. The remaining portion will be imported by Shell Pakistan Ltd. and Caltex Petroleum Corp., other OMCs operating in Pakistan.

Deregulation; price decontrol

The govern ment of Pakistan traditionally has managed the import, refining, distribution, and pricing of petroleum products. The role of OMCs operating in the country was restricted to procuring products from the state-owned oil company and then storing them at their installations.

The products were then transported to the OMCs' depots throughout the country. From there they were supplied to retail sites to be sold at government-prescribed prices.

In the past, the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Resources set and maintained uniform prices of petroleum products throughout the country, irrespective of the distance of retail sites from the depots or installations. This was achieved through a freight pool system.

The government maintained a particular price structure by means of subsidies and taxes. For example, gasoline was highly taxed, but kerosine was subsidized.

Although well intentioned, the system aimed at promoting parity among various economic groups.

It provided limited incentive for OMCs and dealers to operate efficiently because business was being run on set margins that were incorporated into the prices.

Furthermore, it was becoming strenuous for the government to fund the freight pool system. The ministry, therefore, began phased deregulation of the downstream sector.

The freight pool system is being abolished in stages. As a first step, the secondary freight pool system, which involves sales of products from OMCs' depots to the retail sites, has been dissolved. This enables the OMCs to set prices at the retail sites, with the government fixing prices up to the depots.

The second stage will involve dissolution of the primary freight pool system, resulting in a complete deregulation of prices.

The funds saved from the secondary freight pool will be used to furnish the long-awaited increases in dealer margins, which recently have been increased to 3% from 1% of the final retail price. Current plans propose continuation of deregulation of product prices and a phase-out of subsidies over a period of 3 years.

These changes could bring domestic product prices in line with international prices, which would vary through out the country, depending on freight costs and other strategic considerations of the OMCs.

For now, the Oil Companies Advisory Council, on which all the OMCs are represented, has been authorized to revise final retail prices, given a fixed ex-depot price.

These revisions will be made once every 2 weeks, based on the international price of oil and the current exchange rate.

The benefits of deregulation will not be passed on to the consumers until the government removes surcharges from the price structure; these are significant for products like gasoline.

It remains to be seen how quickly this will occur because these taxes and surcharges are a significant source of rev enue for the government. For in stance, the development surcharge on petroleum products contributes up to $550 million/year to the government's revenues.

The transition of the downstream oil sector to a more market-oriented structure will be facilitated through incorporation of a Petroleum Regulatory Authority. This organization will function independently of the government and will oversee both upstream and downstream segments of the business in the country.

The implications of deregulation cannot be assessed accurately at this point. Several possibilities exist, ranging from full-fledged deregulation, as in the case of Thailand and Australia which impacts existing marketers and refiners, to controlled deregulation in which new entrants do not have unrestricted access to the market, as in Japan's case.

With these changes taking place at the marketing level, the questions are when and to what extent the benefits of a free-market downstream sector will be experienced by the players involved.

The author

Hassaan S. Vahidy holds an MA in economics from the University of Hawaii at Manoa and an MBA and a BS in engineering. He is currently a senior associate at FACTS Inc. and a researcher at the East-West Center in Honolulu, involved in downstream oil and gas research for the Asia-Pacific and Middle East regions. Prior to this position, Vahidy worked for Royal Dutch/Shell in Pakistan.