OPEC'S EVOLVING ROLE: OPEC capacity potential needed to meet projected demand not likely to materialize

It was in the aftermath of the first oil price shock of 1973-74 that the question of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries' production capacity was initially raised.

Until then, no one had bothered to tackle this secondary issue, as OPEC's capacity was regularly increasing by leaps and bounds-especially during the prolific 1960s. For the major international oil companies operating in OPEC-member countries, it was an embarrassment of choices rather than limitations. Back then, there was no concern about a capacity ceiling; the sky was the limit. When, for example, a supergiant oil field such as Iran's Marun could be tapped for 1 million b/d within 10 years of its discovery (for an ultimate capacity of 1.5 million b/d), why should the industry worry about capacity limits?

Historical background

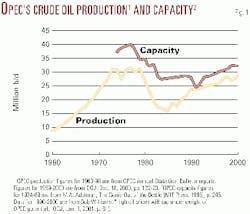

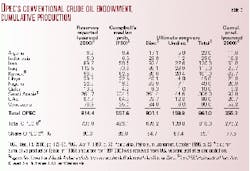

In 1974, OPEC's total production capacity stood at just over 37 million b/d for an average annual output of 31 million b/d-a safe spare capacity of over 6 million b/d, or 20% of total production (Fig. 1). OPEC capacity would peak at roughly 40 million b/d in 1977, before beginning a gradual decline that bottomed out in 1991 at 24.3 million b/d and then inched back to over 31 million b/d a decade later. It is worth noting that the two major capacity decreases were the direct consequences of the two Persian Gulf wars of 1980-88 and 1990-91.

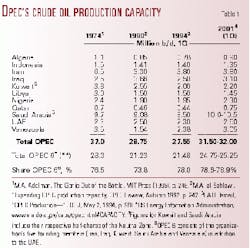

A breakdown for OPEC capacities in selected years is presented in Table 1. As can be seen, Saudi Arabia now accounts for a third of OPEC capacity, and the OPEC 6 (namely Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Venezuela) control roughly four-fifths of total capacity. Furthermore, during the 1990s, individual capacities within OPEC remained rather stable, and total capacity grew by only 10%, or 3 million b/d. The lion's share of this increase went to Venezuela, which doubled its capacity (up 1.5 million b/d), and Saudi Arabia (up 1.0 million b/d).

Present production, capacities

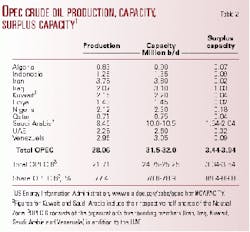

During the first quarter of 2001, OPEC production and capacity, respectively, stood at 28.1 million b/d and 31.5-32.0 million b/d (Table 2). These statistics yield an implied surplus capacity of 3.4-3.9 million b/d, roughly equivalent to 12-13% of actual output.

As a general rule, for any sustainable production level, an excess capacity of at least 10% should be available as margin. In other words, OPEC's present excess capacity is only a notch over the required minimum.

This state of fact is far from surprising, because in order to develop and subsequently maintain an excess capacity, two major requirements have to be fulfilled: 1) the extra capacity has to be created-an expensive proposition estimated at an average of $7,500/b/d of capacity for the Persian Gulf area1; and 2) its upkeep has to be paid for year-in and year-out. Saudi Arabia must be paying at least $1 billion/year for the upkeep of its 1.5-2.0 million b/d spare capacity, or roughly $500-650/b/d of mothballed capacity.

Thus, not many OPEC members can afford to pay such yearly expenses for sustaining a surplus capacity. Here again, Saudi Arabia seems to be a minority of one among OPEC members. In addition, if Iraq also has a substantial surplus capacity, this has more to do with geopolitics and UN sanctions than with any deliberate policy planning.

Reserves, cumulative production

Estimates of global petroleum reserves in general and that of OPEC in particular have always been, and will tend to remain, the subject of intense debate among industry experts.

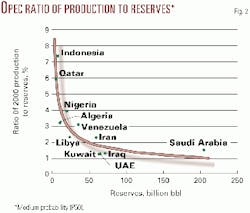

Divergence over reserve estimates is the rule rather than the exception. For example, as can be seen in Table 3, there is a 250 billion bbl discrepancy between the proved OPEC oil reserves reported to OGJ and the median probability (P50) compiled by C.J. Campbell. In this article, OPEC's petroleum reserves (i.e., P50 discovered, undiscovered, and ultimate) will be based upon the latter's estimates (as presented in Table 3) in order to preserve consistency among different types of reserves.

Interestingly, in a general comparison of Tables 2 and 3, a link was found between OPEC members' production in 2000 and their respective median-probability P50 reserves: the former was found to be inversely proportional to the reserves' square root (Fig. 2). A nonlinear fitting of the resulting trendline yielded this equation:

Y = 13.55/ the square root of X, with a standard error of 0.99% on production.

Capacity dynamics

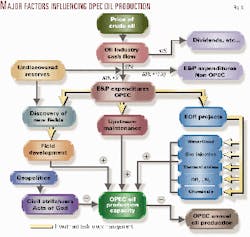

In general terms, crude oil production capacity is a dynamic concept that is constantly changing with time; planning and investment are required just to maintain it at a given level. OPEC is no exception to that general rule.

Five major factors will influence OPEC production capacity over time (Fig. 3). Four of these factors are somehow dependent on the price of crude oil, because not only do "crude oil prices and price expectations provide a crucial component in investment decisions,"2 but they also impact directly industry's overall cash-flow. And as BP Chief Executive John Browne of BP has noted, "Historically, the industry has reinvested a remarkably consistent 60% of cash flow."3 This general rule was once again underscored in the past few years as the consequences of the price trough of 1998 and the price upswing of 1999-2000 became clear; in 1999, worldwide drilling activity shrank by 25%,4 and in 2001, it is expected to jump by at least 20%.5

The five major factors influencing capacity are succinctly reviewed here, beginning with the positive ones:

- Upstream maintenance. This factor is crucial for most OPEC producers, because their most prolific fields are very old-especially those of the OPEC 6 (Table 4). And naturally, the older the field, the more attention and maintenance work it requires.

- Enhanced oil recovery projects. Secondary and even tertiary recovery are very much on the agenda of all OPEC members, because this still is the easiest and cheapest way to boost production-provided adequate technologies and management systems are used.

- New discoveries. In the long term, though, only fresh oil fields will significantly crank up production capacities. And future discoveries depend upon two factors: 1) amount of undiscovered reserves and (2) capital investment for exploration and production. But, at a certain stage, even money might prove unable to secure new discoveries (e.g., in the US).

- Annual production from reserves. The larger the production from reserves, the more negative the impact on production capacity. Any restraint on crude output evidently helps to maintain capacity. For example, Iraq was forced twice (in the 1980s and then in the 1990s) to drastically curtail its production; this unwanted boon will come back to pay dividends in the 21st century.

- Geopolitics. Last, but certainly not least, geopolitics can come to upset programmed capacity expansion in any of the OPEC countries; all being Third World countries, none is immune to the effects of civil strife or war. That is especially true of the six OPEC countries bordering on the Persian Gulf-the world's most volatile region after Jordan's West Bank and the Balkans.

OPEC's future capacity

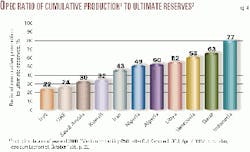

Of the 11 OPEC members, the five smaller producers-namely Algeria, Indonesia, Nigeria, Libya, and Qatar-don't stand much hope for future capacity expansion, as they are already struggling to keep on par. All five have already produced at least half of their ultimate reserves (Fig. 4). Record-holder Indonesia has even produced over three fourths of its estimated oil resources.

Moreover, the five's undiscovered reserves amount to a total of 20 billion bbl (Table 3), which represents only one eighth of OPEC's total. These undiscovered reserves are also a pittance when compared with the five's total discovered reserves of 123 billion bbl.

Thus, for any future increase in production capacity, the limelight will inevitably have to fall upon the OPEC 6 countries.

OPEC 6

In terms of undiscovered reserves, the OPEC 6 account for no less than 87.4% of the organization's undiscovered reserves, a figure that speaks for itself.

The predicament of these six members will be briefly reviewed; their order of precedence will be in reverse to their respective undiscovered reserves:

Predictions of major organiztions

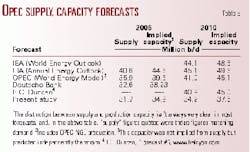

The major predictions of some international organizations for oil supply in 2010 and 2020 are summarized in Table 5. Most of these forecasts seem highly optimistic and rather improbable, but they already have been discussed in detail elsewhere8.

Suffice it to say that, on the one hand, the long lead times required by the global oil industry to discover, develop, and bring to market reserves should be highlighted.

And, on the other hand, it should be borne in mind that if the price of crude oil is right (as amply advocated by Prof. M.A. Adelman of the Massachussets Institute of Technology,9 that allows for added investment (Fig. 3) and thus enhanced capacity-building.

Conclusion

Relying on OPEC to provide the oil required for increasing world demand over the next 2 decades doesn't seem justified, and the present predictions for future OPEC capacity made by international experts look very much improbable, especially given the petroleum industry's inevitable long lead times.

Unless the world would be ready for an extraordinary effort as, for example, addressing itself to the "$1 trillion structural underinvestment in the energy industry" noted by Archie Dunham, the Conoco Inc. chairman and CEO, at the March 2001 Middle East Petroleum and Gas Conference at Dubai,10 there doesn't seems to be much hope to attain the capacities presently being predicted.

Finally, geopolitics could still come to upset the most sophisticated of plans. Two Persian Gulf wars were fought in the past 2 decades. "Jamais deux sans trois" goes the adage.

Acknowledgment

The author wishes to thank Miss Behdis Islamnour for having designed and compiled the articles' tables and figures.

References

- Among others, see I.A.H. Ismail, "OPEC Production-2," OGJ, May 9, 1994, p. 62.

- E.J.P. Browne, "A Global Outlook and Prospects for the 1990s," OIL GAS-European Magazine, 1/1992, p. 14.

- Ibid.

- OGJ, Mar. 20, 2000, p. 70.

- OGJ, Jan. 8, 2001, p. 22.

- Luis E. Giusti, "Venezuela's energy opportunities rest on political climate, new legislation," OGJ, Jan. 8, 2001, p. 56.

- Fadhil J. Chalabi, "The Opening of Iraq," OGJ, Feb. 14, 2000, p. 41.

- A.M. Samsam and F. Shahbudaghlou, "IEA, OPEC oil forecasts challenged," OGJ, Apr. 30, 2001.

- M.A. Adelman, "The Genie out of the Bottle," op. cit. (note 2).

- Bob Tippee, OGJ Online, Mar. 27, 2001.

The author

Ali Morteza Samsam Bakhtiari is a senior expert in the corporate planning division of the National Iranian Oil Co., Tehran. He specializes in questions related to the global oil, gas, and petrochemical industries, with special emphasis on the Persian Gulf and OPEC. Formerly, he lectured on design and economics at the chemical engineering department of Tehran University's Technical Faculty. He holds a PhD in chemical engineering from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology at Zurich.