Mexico's New Energy Era: Gas output to grow further in Mexico's Burgos basin

Aggressive exploration and development of the Burgos basin in northeastern Mexico is expected to result in substantial increases in nonassociated gas production over the next 2 decades, according to a report published by Gas Technology Institute, Arlington, Va.

Development of Burgos, Mexico's most important nonassociated gas basin, should go a long way toward meeting Mexico's surging gas demand.

As Mexico's gas industry expands and the North American gas transportation network becomes increasingly integrated, the report said, the future impact of Mexican gas supply on US gas markets could be significant.

The study also found that undiscovered resources in the Burgos basin may be dramatically larger than existing estimates published by Petroleos Mexicanos and the US Geological Survey.

The outcome of the Burgos exploitation program will be a key to Mexico's ability to meet its growing demand without greatly increasing imports from the US. However, GTI still projects that Mexico will remain a net importer of US gas through 2015.

The field program is centered on Reynosa and Matamoros and adjacent areas in the states of Tamaulipas, Nuevo Leon, and Coahuila (Fig. 1).

The Sabinas basin lies south of the Rio Grande River centered on Monclova, northwest of Burgos, and southwest of Nuevo Laredo. Pemex discovered 17 fields in Sabinas in the 1950s-70s and started production in 1976.

Apparently inactive in recent years, Sabinas produces from Cretaceous rocks and lacks the younger Tertiary section productive at Burgos.

Supply-demand projection

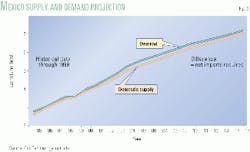

GTI's existing baseline projection is that Mexico's gas demand will grow faster than supply in the near term, mainly due to rapid industrial growth, clean air goals, and construction of gas-fired power plants (Fig. 2).

GTI put Mexico's 1999 gas market, 5.6% of the US gas market, at 3.59 bcfd supplied by 3.57 bcfd of Mexican production and minor imports from the US.

The institute projects that demand growth rates will average 6.8% in 2000-05, 3.2% in 2005-10, and 2.1% in 2010-15. It projects domestic supply growth at 6.1%, 3.5%, and 2.4%, respectively.

This leads to demand of 5.5 bcfd in 2005, 6.5 bcfd in 2010, and 7.2 bcfd in 2015, compared with projected domestic supply of 5.3 bcfd in 2005, 6.2 bcfd in 2010, and 7 bcfd in 2015.

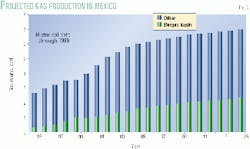

GTI sees Burgos basin output climbing from the 1999 rate of 970 MMcfd to 2.3 bcfd in 2015 (Fig. 3). Associated gas production from southeastern Mexico will also increase substantially, in line with crude oil production gains there.

Net imports to Mexico are expected to increase from less than 150 MMcfd the past few years to 267 MMcfd by 2005.

Export capacities as of December 2000 are 970 MMcfd to the US from Mexico and 1.37 bcfd to Mexico from the US, some of it through bi-directional pipelines.

Thus Mexico, if it exported no gas to the US, could import 38% of its current annual demand, found the study, conducted for GTI by Energy & Environmental Analysis Inc.

Emphasis on Burgos

Pemex has exclusive E&D rights in Mexico and has until now emphasized oil developments.

Most gas production is associated and dissolved gas from oil fields in southeastern Mexico far from major consuming areas in the north and northeast.

Pemex, starting in 1998, began to apply advanced 3D seismic, drilling, and hydraulic fracturing techniques to expand Burgos basin dry gas production.

Pemex figures show North Region gas production growing to 447 bcf/year in 1999, including 354 bcf from Burgos, from 200 bcf in 1995 when Burgos contributed 110 bcf.

Pemex reports completing 100-125 wells/year throughout Mexico in most of the 1990s, reaching 234 completions in 1999. By comparison, the Texas-Louisiana Gulf Coast province claims 2,500 of the 20,000-23,000 completions/year in the US.

Burgos basin drilling rose to 194 wells in 1999 from 9 wells in 1993, with 1999 success rates of almost 100% for development drilling and more than 50% for exploratory drilling.

Burgos production grew 26-51%/year in 1997-99, but monthly data in 2000 show it leveled off in mid-1999. The reason is unclear but could be pipeline capacity constraints.

About 85% of 1999 Burgos production came from the eight largest fields, the largest contributors being Culebra and Arcos (Table 1). The other six fields are Arcabuz, Cuitlahuac, Merced, Monterrey, Pandura, and Reynosa.

Burgos basin evolution

Burgos exploration began in the 1920s, before nationalization of the industry in 1950, as oil companies tried to extend known Tertiary producing trends from Texas into northern Mexico. Burgos began producing in 1945.

Major Burgos productive intervals are Paleocene, Eocene, Oligocene, and Miocene in age.

Producing formations are equivalent to the Fleming Group of Miocene age, Vicksburg, Frio, and Anahuac of Oligocene age; Upper Wilcox, Mount Selman, Cook Mountain, Yegua, and Jackson of Eocene age; and Midway and Lower Wilcox of Paleocene age.

More than 100 gas accumulations were discovered through 1997, when Pemex announced a $5.5 billion, 15-year project to increase gas production from 500 MMcfd at the time to 1.4 bcfd and maintain that rate through 2007. The company said it would drill more than 1,000 development wells and 50 exploratory wells.

Because outside oil companies have not been permitted to operate in Mexico since nationalization, Pemex has contracted most of the Burgos work to service companies, including Schlumberger Ltd. and Halliburton Co.

Whereas a large share of earlier production came from high-permeability Frio and Vicksburg reservoirs, more recent development has concentrated on low-permeability Wilcox sands.

Below the Burgos Tertiary sequences are Cretaceous sediments, and below them is a Jurassic section that does not produce in the region but could have significant potential. The Jurassic section correlates with the highly productive Norphlet sandstone occurring off Alabama.

Burgos, Texas Dist. 4

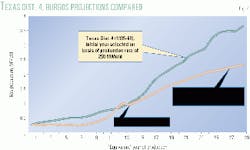

GTI projects Burgos production rising to 2.3 bcfd by 2015, with growth rates averaging 13%/year the next few years and moderating after that, said John Cochener, GTI project manager.

The institute compared Burgos with Texas Railroad Commission Dist. 4, a 15-county coastal area north of the Rio Grande, because of close geological similarities.

Dist. 4 reached 250 MMcfd in 1935, and production rose to 3.6 bcfd 29 years later and to 4.5 bcfd in 1971. Burgos produced 250 MMcfd in 1987, and GTI's projection is for it to be producing 2.3 bcfd in 2015 (Fig. 4).

Given that Dist. 4's growth occurred in earlier decades, when production technology was far less advanced, prospects appear good for substantial growth at Burgos.

Size of the productive area may also indicate greater potential from Burgos than even GTI has forecast.

Dist. 4 covers 17,200 sq miles. Burgos production is developed on 10,000 sq miles, but the basin's extent is far greater. Reaching out just 50 miles from the existing productive area yields an area of 40,000 sq miles, more than double the size of Dist. 4.

Gas output considerations

Mexico's 1999 raw natural gas production totaled 4.8 bcfd, including 3.5 bcfd of associated gas and 1.3 bcfd of nonassociated gas. The volumes include venting and flaring, reinjection, and shrinkage.

Dry, marketed volumes were 3.6 bcfd in 1999.

The large difference between raw gas production and dry marketed production relates to extensive venting and flaring in southeastern basins. Mexico vented and flared 2.8-5.6% of gross production in the 1990s, compared with about 1% in the US, US Energy Information Administration figures show.

Crude oil exports provide major revenue to the Mexican government. GTI assumes that Mexico's 3 million b/d of oil production will grow to 3.4 million b/d in 2001, 3.7 million b/d by 2002, and gradually stabilize around 3.8 million b/d through 2015.

Much of the increase is expected from the Cantarell nitrogen enhanced oil recovery project in the Bay of Campeche. Injection of nitrogen avoids reinjecting produced natural gas for pressure maintenance and frees this gas for domestic sales.

The Mexican energy undersecretary in 1999 said Mexico would expand production to more than 900 MMcfd by 2007 in the Macuspana province in southern Tabasco, but no further details about this project have been forthcoming.

Resource estimates

Existing estimates of undiscovered resources in the Burgos basin appear to be quite conservative, the GTI study found.

Some 7.6 tcf of gas resources are proved in more than 100 accumulations in the Burgos basin.

The Pemex assessment of reserve-appreciation potential for the Burgos basin is 4.2 tcf by GTI's allocation, and the USGS assessed conventional new field potential to be 5.5 tcf as of Jan. 1, 1993, in a study released in 1994.

This 9.7 tcf can be compared with GTI's current volumetric estimate for the Texas Gulf Coast of more than 100 tcf for similar geological conditions. Volumetric yield analysis involves the determination of ultimately recoverable hydrocarbons, discovered and undiscovered, per cubic mile of sedimentary rock.

GTI projects hydrocarbon yield of 0.230 MMboe/cu mile for the Texas Gulf Coast. The USGS 1994 assessment plus Pemex data on proved recovery and reserves appreciation give a yield of 0.048 MMboe/cu mile, very low compared with most other North American producing areas.

An additional 11-65 tcf of gas resources would be required to increase the volumetric yield to the 0.075-0.200 MMboe/cu mile observed in the US. The additional gas could come from any combination of reserve appreciation, new fields, or nonconventional reservoirs.

The addition of 11-65 tcf of gas would result in a total undiscovered resource base of 21-75 tcf, equivalent to 2.7-9.8 times current proved recovery, GTI found.