Iranian oil buybacks: a formula no one likes

Iran's thriving oil industry in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s-when its daily crude oil production reached the highest in the Middle East in 1 year and subsequently remained the second highest within the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries-suffered massive losses during the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war.

Even with production capacity gradually built up since the ceasefire to about 4 million b/d-up from a 1.3 million b/d output in 1981-the National Iranian Oil Co. (NIOC) is still a small shadow of its 1974 self, when output surpassed 6 million b/d.

The restoration of the petroleum sector to its prerevolution rank has become a high priority, if not almost an obsession, in Iran's 1990s economic agenda. And the goal of 5 million b/d of capacity has been incorporated into each of the country's three successive 5-year economic development plans-with the latest now stretching to 2004.

Despite valiant efforts by three different oil ministers, half a dozen structural reorganizations of NIOC into scores of spin-off companies, and interminable changes in the oil ministry's senior management cadres, the 5 million b/d output target is not yet in sight. The latest agreements with companies from Italy and Japan are expected to raise sustainable output capacity to 4.4 million b/d from less than 4 million b/d today.

Physical, technical, and political factors have been responsible for the delay.

Physically, considerable war damage, poor maintenance of the oil wells, and imprudent and excessive extraction from aging reservoirs have been the main reasons for continued production shortfalls.

Technically, the absence of indigenous oil technology and modern management know-how, along with a crippling shortage of investment capital, have made substantial involvement by foreign oil companies almost inevitable.

Political hurdles

Washington's economic sanctions involving US oil companies' trade and investment in Iran's oil industry and the ILSA (Iran-Libya Sanctions Act) statute extending the boycott to foreign energy entities have also served as holdups to substantial capacity expansion.

Politically, and by far the most stubborn handicap, however, has been the Islamic Republic's ideological position and the constitutional injunction against foreign ownership of mineral resources.

Iran's foreign economic policy for almost the last 100 years has always been an oil-dominated one. The Iranian oil nationalization in 1950 and subsequent do- mestic takeover of oil production, refining, and marketing has since made "local control" almost a matter of political faith. Built on this ultranationalistic sentiment, Article 81 of the post-revolution constitution-spawned by the so-called Islamic Marxists and prominent "red clerics"-strictly bans any "concessions" to foreigners in production or commerce. No foreign ownership-and, by some interpretations, no production-sharing-is allowed on energy investment or operation.

Buy-back model

To circumvent this constitutional ban amidst a desperate need for foreign capital and updated technology, a formula called buy-back, starting in 1995, has since served as a standard model for Iran's oil and gas deals with foreign firms.

Under this misnamed model-there is no purchase or sale involved-foreign energy companies agree to invest a specific amount in a designated field for output enhancement or new exploration in return for a given compensation. These compensations ordinarily consist of a sum, covering initial investment plus interest and profit, to be received "in kind" over several years out of the project's output once it is completed.

The contract terms are usually for about 7 years, and returns to foreign investments commonly involve a recovery period of about 5 years. In this arrangement, foreign investors receive no direct equity stake in the venture, but they are generously compensated for their capital and technical inputs. And, should the project's output be insufficient to meet the investor's contractual entitlements, the difference will be made up by the NIOC, out of other projects' outputs.

Over the past several years, a number of oil and gas deals have been concluded between NIOC and such foreign energy majors as TotalFinaElf SA, Royal Dutch/ Shell Group, and ENI SPA, among others. Yet, out of 24 development and 17 exploration projects offered to international oil companies (IOCs), fewer than a dozen contracts worth a combined $11.5 billion have so far been officially reported as finalized-against an ambitious target of close to $50 billion (see table).

Apart from NIOC's frequent internal reshuffling and its staff's technical inability to screen project bids on time, the slow progress in negotiations over a multitude of contracts has been mainly due to the unpopularity of the buy-back formula in both domestic and foreign circles. Iranian politicians of various stripes in and out of the Majlis (national assembly) have repeatedly denounced the buy-back terms as insufficiently safeguarding the national interests, while IOCs have found the formula insufficiently attractive for the prospective venture.

Iranian objections

Objections in various Iranian quarters to the buy-back arrangements point to several presumed drawbacks:

- Foreign contractors receive a hefty return (London Interbank Offered Rate plus 1% interest; 15-20% profit) on their investment, without assuming any geological risk, as the fields are already discovered and well-defined. Nor do they take any financial risks resulting from a potential decline in world oil prices, because their returns are fixed and guaranteed.

- IOCs have no incentive to complete their projects below the cost budget, no obligation to employ their state-of-the-art technologies, and no desire to transfer know-how to the host country as long as they can get away with it.

- Foreign parties tend to maximize output extraction in the first few years of the operation in order to recoup their investments within a scheduled time, without attention to an optimum recovery schedule over the reservoir's lifespan and regardless of possible permanent damage to the oil fields.

- Because the total project outlay, the duration of repatriation of investment, and the share of the contractor in the new finds are fixed and given, Iran may actually lose in the venture if its OPEC quota is not in- creased, or if oil prices decline, in future years.

- Buy-back contractors usually shy away from exploration projects and are customarily attracted to development of already-discovered fields.

- Because the formula involves no long-term investment, it does not necessitate an effective transfer of the latest technology to the host country.

- Foreign contractors currently offer no guarantees of a certain level of production once the project is finished and bear no responsibility for the shortfalls from projected targets.

Foreign investors' objections

Buy-backs are equally disliked by foreign investors. From an IOC's standpoint, the formula offers inadequate incentives compared with the production-sharing agreements (PSAs) available in some other oil producing countries, such as Kuwait and Venezuela. Complaints are legion:

- Foreign companies are mere NIOC service contractors; they cannot "own" any oil or gas reserves to show as their assets. And if oil prices should rise in the coming years, there is no share for IOCs in new higher profits.

- The short duration of buy-backs is not conducive to long-term investment planning. The limited span of projects requires that foreign companies line up a string of several separate deals to build up a meaningful long-term business relationship with the country-not an easy or practical task.

- Because the Iranian government generally insists on only a 10% contingency reserve for cost overruns, foreign companies that exceed the 10% allowance will have to make up the nonrecoverable difference, which will reduce projected returns on investment.

- Obligations to give local contractors some 30% or more of the total contract value are found to be not only a costly nuisance but also an incursion into total returns.

- Because NIOC takes over the buy-back projects once they come on stream, foreign companies fear that Iran may not be able to operate them as efficiently as might be expected, and thus they may be blamed for the outcome.

Reforms proposed

In view of these dissatisfactions on both sides, NIOC has recently proposed to insert some risk-reward provisions into the new buy-back contracts whereby foreign investors would be penalized if they do not reach agreed production targets but would be rewarded if they exceed the targeted output.

On the issue of responsibility for prudent and efficient operation, once the project is finished and handed over to NIOC, it is suggested to have a joint supervisory committee oversee and monitor post-project operations-thereby placing the responsibility for optimum output decisions on both parties.

Neither of these new terms is equally satisfactory to both parties.

The arguments are compelling. On Iran's side, it is argued that overshooting or undershooting oil production targets-as the basis for rewards and penalties-can always be attributed to, or blamed on, circumstances beyond the foreign contractor's control. On the IOC's part, it is held that tangible rewards for extra performance may not be meaningful as long as the IOC's role in post-handover production is limited to "monitoring" and not "deciding" the field operations.

Given both sides' lukewarm response to the new buy-back terms and Iran's current legal restrictions on PSAs, future arrangements may ultimately tend to favor more-conventional service contracts for engineering, construction, and transfer, whereby NIOC will assume total control and whereby IOC will serve as hired contractors. And once Iran succeeds in increasing its foreign exchange reserves, or possibly enters the world capital markets on its own, the current buy-back model is thus likely to lose its present significance.

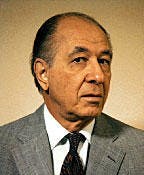

The author

Jahangir Amuzegar, a native of Iran, is an international economic consultant based in Washington, DC. He served in the Iranian government as minister of commerce (1962-63), minister of finance (1963), and ambassador-at-large for economic affairs in Washington (1963-79). He represented Iran and several other countries on the executive board of the International Monetary Fund during 1974-80. Amuzegar has written more than 50 articles and 7 books on Iran, oil, and economic development, including his latest book, Managing the Oil Wealth: OPEC's Windfalls and Pitfalls (1999). He has taught at a number of US universities and received his MA in economics from the University of Washington and his PhD in economics from the University of California-Los Angeles.