COMMENT: RELUCTANCE TO TRADE A RISKY POSITION IN OIL MARKET

Marshall ThomasThe oil industry is re-engineering, restructuring, down- sizing, etc. as part of a draconian effort to reduce costs and enhance profit margins. Benchmarking of corporate results against the competition is in vogue, with a view to challenging per- formance at every level of management.

PVM Oil Consultants Inc.

Teaneck, N.J.

The bold "can do" attitude behind today's oil industry revolution in management grinds to a halt when the subject is oil trading. Mention speculation, oil pricing mechanisms, market risk-taking, or derivative instruments, and many in senior management and the corporate boardroom lapse into worried silence.

We have seen what can go wrong when a commodity trading function is not tightly managed, and we have also seen the less visible negative impact when a supply function takes unwise risks under the umbrella of hedging. As the newspapers highlight rogue traders at Daiwa Bank and Barings and the spectacular market reverses at Metallgesellschaft and Showa Shell (Japan), the trading managers at many oil companies receive worried calls from their chief executive officers: "We are not speculating or playing derivatives, are we?"

The responses are typically, "No, boss, we only hedge. We never take big risks. No need to worry." The sighs of relief are audible. Everything is okay.

The reality is, everything is not okay. This is particularly the case at many companies in retreat from market participation. When an oil company finishes restructuring and reconcentrating business direction, setting new investment and performance criteria, it is still left with the huge variable of price. Any corporate management that fails to act aggressively in the trading sector by pursuing the best possible oil price as a buyer or seller isn't living up to its responsibilities to shareholders.

MARKET RETREAT

At a time when virtually all long term crude and product supplies are market-linked, the base load supply functions are inexorably connected and exposed to the vicissitudes of daily trading developments. The market linkages extend from the strictly domestic arena to the big European and Asian trading centers and interact one with another. This means the exposures are essentially built-in and unavoidable (whether one has an active or passive market approach).

By not trading, a company is taking a position: namely, not to choose the timing and opportunities available to "select" both a raw material price and a finished product value. The passive "price taking" role may be a valid corporate strategy. However, a company may be forgoing meaningful profits in the crude/refining/supply/trading chain with a passive approach. We think these choices must be conscious ones that are subjected to rigorous scrutiny.

MARKET IMPERFECTIONS

The oil markets and market pricing mechanisms are not perfect. Repeated references in the trade press to market manipulations, squeeze plays, and dissatisfaction about Brent- related pricing mechanisms are indicative of some long simmering structural problems associated with the markets. PVM assessed these problems in a multi-client study entitled Formula Pricing Mechanisms - The Search for New Solutions.

Today's oil trading maladies are largely the consequence of liquidity problems created by those who fail to see the need to participate in the markets, which they themselves rely on as the day-to-day value of their crude oil assets. The lack of trading volume pushes the trade publications into making price assessments on the basis of limited business, and discrepancies can and do result.A brief look at the Brent contract for differences (CFD) markets illuminates the issues at stake, as well as the scope and importance of the evolving markets. CFDs are over-the-counter instruments designed to enable market participants to hedge against fluctuations associated with the Dated (physical) Brent prices published in the trade press.

The Dated Brent quotes are used in the formulas that determine contract prices and oil company/producer nation income for much of the crude flowing into the Atlantic basin.

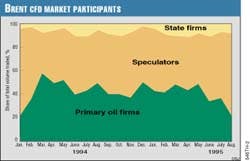

The growth in Brent CFD trading volume has been explosive, though the amount of trading activity is prone to some wide month-to-month swings (see charts).Contrary to common wisdom, the Brent CFD trade is not simply a playground for traders but involves a substantial amount of trading activity on the part of primary oil companies (majors, minimajors, and independent refiners alike). The amount of Brent CFD business done by speculators (both oil traders and the Wall Street players) is roughly equal to the combined volume of trade done by the primary and state oil companies. Within the ranks of the oil companies, the majors play the largest role in Brent CFD trade, with both the minimajors and independents also rather active.

WINNERS AND LOSERS

Participants in the Brent CFD trade have chosen to take a proactive role, even though they are aware the market is less than perfect at times. Rather than opt out, they have committed resources to understanding the dynamics of the market and figuring out how to profit from them. Participants believe that, since the existing market mechanisms are in place, it is their job to understand them and the consequences of doing business.

The sideline sitters and nonparticipants have a long litany of "reasons" for staying out of the markets that determine their bottom line. The approach of Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries producers in criticizing the spot markets rather than learning how to effectively participate is a prime example of how not to handle markets - and it has cost them untold millions of dollars.

Since there are winners and losers in every commercial transaction, it is not surprising that any pricing mechanism will in due course be viewed by some sectors of the industry as being abused, biased, or unfair. As views are articulated in public venues, they are seized upon by the nonparticipants as a vindi- cation of their decision to stay out of the market.

For all the noise about the imperfections of present pricing systems, structural change is slow in coming. While there is almost a natural industry lethargy when it comes to tackling trading issues, some changes may be coming.

THE DECISION TO TRADE

The question of whether to trade, and how much trading is appropriate for a specific company, should be addressed from two vantage points:

First, there is the philosophical decision on whether or not to get more involved in trading. That depends on what the company management has in mind, which in turn determines the degree of risk, the operating structures, and the management controls.

Secondly, if it is determined that trading activity will be a core business for the company, numerous practical issues must be addressed in a cohesive and organized fashion. Most signifi- cantly, senior management must develop a comprehensive understanding of trading-related issues. Given the implicit risks and corporate exposures, the job cannot be left totally to subordinates.

DEVELOPING A PROGRAM

To effectively build and manage a trading operation, internal staff resources (often under utilized) should be brought to the task. There is also a need to utilize available outside commercial expertise to provide an independent appraisal of trading structures and effectiveness.

Individual companies should undertake periodic commercial audits to ascertain the effectiveness of their market-related activities and to assess their policies and exposures in trading.

Such reviews should encompass the appropriateness of the trading instruments in use. Management control mechanisms should be reviewed to determine that "mark-to-market" mechanisms are in place, providing an independent evaluation of risk exposures.

Market participants need to periodically review the behavior of the various benchmark pricing instruments and critically assess the ever- changing character and composition of trade par- ticipants.

There should be an integration of the trading and market perspective into the short and longer term decision-making processes. Economic decisions should be reached with the direct input of those involved in the day-to-day commercial oil business.

TIME FOR CHANGE

Despite the barriers to change, restructuring of pricing systems could be in the cards on a number of fronts. Several primary oil companies are very concerned about the lack of liquidity in some market instruments - such as Dated Brent - the inadequacy of sour crude benchmarks, and the need to develop an Asian crude yardstick.

Among the issues presently attracting oil industry attention:

- Increased participation by all sectors of primary industry.

- Benefits to the market of better definition.

- The use of a broader "basket" of trade press pricing services for purposes of determining benchmark crude values in contract formulas.

- Development of more broadly based sour crude benchmarks in both the Mideast and in destination markets like the United States.

MESSAGE FOR MANAGEMENT

When the former Soviet Union and the eastern European satellites embraced capitalism, the senior management of state enterprises experienced an unprecedented "shock" in corporate culture.

The free market exposure, risk-taking, hedging, and speculation were all new experiences.

The pragmatic survivors of communism took a simple approach: They went "back to school" to learn about the new rules of the game, and how to play it profitably.

Many oil industry chief executive officers, directors, and senior managers (including the oil ministers of OPEC nations) would be smart to take note of the adaptability of former communist managers in facing up to the opportunities and challenges implicit in the commercial crude oil business. All of us involved in the commercial sector can contribute to this process of evolution and growth.