Snøhvit development prospects hinge on LNG commerciality

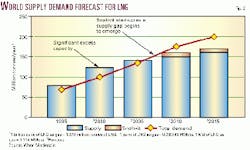

Gas discoveries in the Snøhvitarea of the Barents Sea-currently only marginal economically-could become commercially viable if sufficient LNG markets materialize within the next 6 years, according to a new report by Edinburgh analysts Wood Mackenzie.

Financial feasibility of the Snøhvitproject also will depend on the Norwegian government's provision of full tax advantages to the operators, WoodMac concluded, and on the operators' broad employment of the most recent advances in LNG technology.

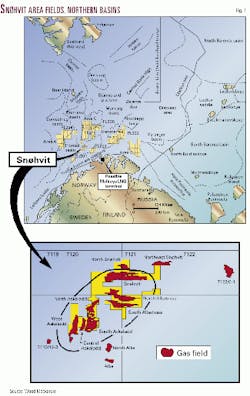

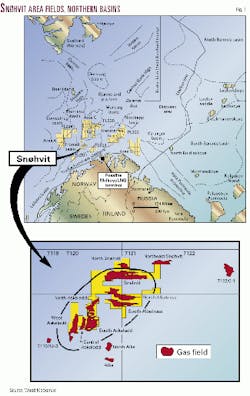

Snøhvitis located in Norway's Hammerfest basin, in the southern Barents Sea. Three fields-Snøhvit, Askeladd, and Albatross-make up the Snøhvitarea. The remoteness of the area makes exploration, production, and transportation costly. Because the distance from existing gas export infrastructure is so great, the Snøhvit partners are planning a multiple-phase LNG program with dual, phased pipelines from the fields to a proposed single-train, onshore LNG plant in Norway.

Statoil would operate facilities for its partners, currently TotalFinaElf SA, Norsk Hydro AS, Amerada Hess International Ltd., RWE-DEA AG, Svenska Petroleum Exploration AB, and Norway State DFI (see table). The operators expect to begin production in 2006.

Statoil and other leaseholders in the Norwegian sector have drilled 56 wells in the area to date and, although they have discovered no commercial oil reserves, they have found a substantial core recoverable resource of about 6.5 tcf of gas and 170 million bbl of condensate in the fields. Operators plan to begin an expanded exploration-appraisal program this summer and expect to drill another nine wells over the coming 2 years.

Capital costs for the project are estimated at 26 billion kroner (2000 value), with total annual operating costs of 500 million kroner, including a carbon dioxide tax levied on at least part of the project.

Snøhvit facilities

Current development plans for the Snøhvit LNG project will require construction of a single-train LNG terminal on the small island of Melkøya near Hammerfest. If a second train were built, WoodMac observed, it would increase output and improve project economics.

Plans call for 18 horizontal wells in the fields-5 in Snøhvit 5 in Askeladd, and 8 in Albatross-and a 140-km, 27-in. multiphase pipeline to deliver condensate and natural gas from the fields to the plant.

Phased development, using the one-train facility, would have condensate-rich Snøhvit field production on stream first, followed by Askeladd 8 years later and Albatross 14 years after initial production begins. Gas produced early from Askeladd could be injected into Snøhvit wells to enhance liquids production.

The project will probably require compression facilities in later phases, both on a floating field platform and onshore, in order to boost recovery.

The partners expect production to reach 4.5-5.6 billion cu m/year (435-542 MMcfd) of natural gas and about 20,000 b/d of condensate. The field gas contains 4-7% CO2, which would require removal at the plant. Statoil will most probably reinject the CO2 into an offshore aquifer, WoodMac noted, which would require a smaller-diameter pipeline-probably 6-8-in.-and one or more injection wells.

After removing CO2 and reserving sufficient gas for the production and liquefaction processes, owners could produce 5.5-6.9 million tonnes/year of LNG for sale. Regasification would then free 387-485 MMcfd of natural gas deliverables. At this production rate, the three fields would have a life expectancy of about 40 years.

Area history, development

Exploration drilling began in the Norwegian sector of the Barents Sea in 1980, with several substantial gas-condensate discoveries made in the central part of the sea in the Snøhvit area. Core gas reserves in the fields are contained in Middle-Lower Jurassic sandstone structures in 300-340 m of water.

While commercial oil discoveries have been elusive, Snøhvit field does contain about 500 million bbl of oil within a thin zone at the base of the reservoir. A rapid breakthrough of gas and water during the production test spelled the end of oil production attempts, as recovery was consequently deemed noncommercial.

Because of technology limitations during early exploration and development, discoveries were not encouraging, and drilling ceased in 1994. However, in an attempt to stimulate continued exploration, Norwegian authorities revised licensing terms in 1996. The revisions enabled group applications, the award of greater equity shares, elimination of drilling commitments for some awards, and the expansion of blocks. Licensing activity continued in 1997 as the Barents Sea Project.

Norsk Hydro, which has had success producing oil from thin oil zones in West Troll, investigated new oil production options for Snøhvit but shelved them in 1999. The picture for oil does not remain totally bleak, however. Recent advances in technology may soon improve commercial prospects for the fields, and exploration plans for the next 2 years could well result in discoveries of oil deposits in more-favorable production environments. The Norwegian Petroleum Directorate is eager to maximize recovery of oil reserves in the Barents and will encourage further investigation of methods to accomplish that goal, notes WoodMac.

The huge Barents Sea region, vastly underexplored compared with the North Sea, contains several distinct geological provinces that hold the potential for major hydrocarbon discoveries.

To date, almost all finds have been located in the Hammerfest basin. Four wells are scheduled for 2000: Norsk Hydro plans to drill one in Area A, in the western part of the sea (Fig. 1); Agip SPA will drill two, on PL229 and PL201, southeast and southwest of Snøhvit; and Statoil will drill the fourth farther east on PL202 in the Nordkapp basin. The company will target Lower Jurassic-Triassic plays in this salt basin, which is dominated by diapir traps.

LNG markets

Establishment of sufficient LNG markets by 2006 is critical to the economic feasibility of the Snøhvit development scheme, the WoodMac report emphasized. Discussions for an earlier LNG gas sales agreement with the Italian electric utility ENEL broke down in 1993, and the owners then shelved that project.

Operator Statoil and six partners (see table) are reportedly interested in attracting additional strategic partners such as gas utilities and other upstream buyers. Gaz de France has expressed an interest in the project in the past. Snøhvit partner TotalFinaElf, itself one of the largest global LNG players, is likely to take a leading role in the venture and could provide a primary market base, according to WoodMac.

The Mediterranean region and US East Coast, viewed as prospective market areas having the most significant demand growth potential, will be principal target markets for Snøhvit LNG. The high cost of LNG transportation gives the Norwegian location a delivery advantage over other supply sources in competing for US and European LNG markets.

Additional growth markets are concentrated in Turkey and in Atlantic markets such as Brazil, Spain, Portugal, and the US. WoodMac notes that Snøhvit is not designed to compete with Norwegian pipeline gas sales, but will, instead, complement them.

Taxes

Total tax liability will have a key impact on the financial viability of the project. The WoodMac report notes that Norway employs a separate tax base for onshore and offshore facilities: onshore rates, which cover standard industrial activities, include a 28% "corporation tax," while offshore upstream oil and gas activities are subject to an additional "special tax" at a rate of 50%.

Norwegian authorities currently favor taxing the entire project, including all LNG terminal facilities, at the higher offshore tax rates. WoodMac reasons, however, that local support for the venture will likely result in political pressure to grant favorable tax status to the project and that two-thirds of costs of the onshore LNG plant will probably be subject only to the more favorable onshore taxation.

Tax advantages would significantly enhance the project's economics. In its feasibility assessment, WoodMac speculates that half of the total operating expenditures will likely fall under the preferable onshore taxation, and half will be taxed at the higher offshore rates.

Economics

The onshore-offshore designation can affect rate of return on investment, which is often decisive for the advancement of marginal projects such as this. Norwegian authorities could restrict the rate of return to a pretax level of 7% by designating the onshore facilities as "infrastructure," which would be a tradeoff for taxing them as onshore facilities.

Financing is expected to be relatively easy, given Norway's low political risk. The ability to offset interest payments against the high marginal tax rate also could turn out to be a bonus for participants when seeking financing. WoodMac's assessment of economics models a break-even LNG price scenario of $2.60/Mcf.

Other variables can affect this project's profitability, positively or negatively-cost increases or decreases, higher or lower production, and fluctuations in the exchange rate-between the time of project initiation and on-stream deliveries. Any or all of these could affect the economics of this undertaking in the future, but the WoodMac study concludes that the project, at this phase of planning at least, is marginal.