NPC study: Proposed regulations to sharply hike US refining costs

Most US refineries and many product terminals can expect exceptionally large costs in refinery and distribution investments within the next 6 years if recently proposed Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) emissions-control policies are implemented as scheduled.

Implementation is expected to cost billions of dollars and could result in possible supply interruptions, price variations, and some facility shutdowns, according to a study by the National Petroleum Council, the US energy secretary's oil and gas industry advisory panel.

NPC released the study late last month (OGJ Online, June 20, 2000).

The study, requested by the Secretary of Energy in mid-1998, investigated the potential impact of four major proposed alterations to product specifications, representing simultaneous changes and timing on a scale unprecedented in the petroleum industry.

Modifications include: reduction of the sulfur content of gasoline to 30 ppm (EPA's "Tier 2 rule" issued in December 1999); reduction of the sulfur content of on-highway diesel fuel to 30 ppm (Tier 2 rule); the elimination of methyl tertiary butyl ether (MTBE) and other toxic emissions from gasoline (EPA, Mar. 20, 2000); and a request by the automobile industry to reduce the driveability index (DI) of gasoline to 1,200 degrees F. The study did not examine the effects of vehicle emissions or the cost-effectiveness of the changes.

NPC examined existing reports and compiled new data to determine process technology availability and readiness, refinery production capability, product delivery considerations, and facility implementation requirements and capabilities.

Key to successful implementation of these proposals, according to NPC, is the timeliness of the permitting process, sufficient lead time for implementation, and the sensible sequencing of new requirements, with no overlapping of projects.

Simultaneous timelines for implementation would result in shortages of materials, supplies, and services. It would also create delays in meeting regulatory deadlines and increase the potential for temporary-but major-regional supply disruptions, along with significant price fluctuations.

In addition to the benefit of a cleaner environment, US consumers can expect higher prices for products as refiners recover their costs. Efficiency improvements may offset some cost increases, but it is unlikely that they will be sufficient to maintain premodification status quo financially.

With timely permits, however, and sufficient lead time to respond to each fuel-quality change, NPC says that it is possible for the industry to satisfy product demand for the more-stringent product specification requirements studied.

Gasoline sulfur reduction

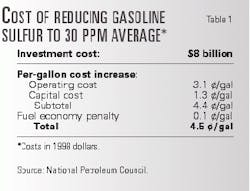

The NPC says an investment of at least $8 billion (1998 dollars)-twice the EPA's estimate-will be required to reduce sulfur content of US gasoline from the current level of 340 ppm to an average of 30 ppm during 2001-05. This estimate excludes California, where the industry has already invested about $4 billion for sulfur reduction in California gasoline supplies.

Costs could be higher still if a significant number of refiners implement fluid catalytic cracking feed sulfur reduction in addition to FCC product desulfurization.

NPC also examined the potential to reduce gasoline sulfur to levels lower than 30 ppm and said that, although processes exist to facilitate the lower levels, costs are expected to increase dramatically with each increment of sulfur reduction, and that most such technologies would be "operating beyond the range of demonstrated experience."

Desulfurization equipment must be installed in nearly every US refinery, along with 400 product distribution terminals and 1,300 product terminals.

The refinery processing cost increase to provide 30 ppm sulfur gasoline is estimated at about 4.5>/gal (Table 1), which includes operating and capital costs at refineries and in the product-distribution system. Table 4 shows individual factors that reconcile NPC's $8 billion investment estimate with the $4 billion March 1999 MathPro estimate, which is the basis for EPA's estimate.

These figures do not include additional costs to be incurred for blending, handling, and distributing low-sulfur fuels in refineries, pipelines, terminals, trucks, and retail stations.

If environmental permits can be acquired expeditiously, it is likely that engineering, equipment manufacturing, and construction resources will be sufficient to meet Tier 2 rule requirements during 2004-06, the report notes. However, engineering and construction resources will be tight during peak workloads and would be insufficient if there were an overlap of product specification changes or other substantial construction requirements.

An increase in stationary source emission-control requirements or a requirement for significant increase in fuel ethanol production could result in delays in meeting EPA timetable requirements.

Diesel sulfur reduction

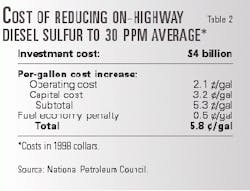

A $4 billion investment at 80% of US refineries over a 7-year period will be needed to reduce on-highway diesel sulfur to an 30 ppm average from about 350 ppm, according to the study. The cost increase of providing 30 ppm on-highway diesel is estimated to be about 5.8>/gal (Table 2). Even Californian refineries will require additional equipment, because on-highway diesel sulfur levels in California average about 140 ppm.

If the timetable calls for 30 ppm diesel fuel to be available in 2007 for model year 2008 vehicles, there should be sufficient industry resources to accomplish delivery with little risk of supply interruptions other than those normally associated with implementation of a new product specification program.

If, however, an earlier schedule (2006) were mandated, the program would overlap with the sulfur reduction in gasoline Tier 2 rule, resulting in inadequate engineering and construction resources during peak periods. The consequences would most likely be implementation delays, increased costs, and inability to comply with regulatory timeline requirements.

A mandate to reduce sulfur levels to below 30 ppm would automatically require greater investment costs for new, higher-pressure hydrotreating units in about 90 refineries. According to the study, it also would be very difficult for existing distribution systems to maintain the integrity of gasoline or diesel at levels below 30 ppm.

More study is needed, the report noted, to fully evaluate technology options, refinery operations, and the capabilities of distribution systems.

Cleaning diesel to this degree would necessitate new, higher-pressure hydrotreating units, sending costs upward, and would result in likely shortages and inadequate supplies. In question is the ability of existing distribution systems to maintain the integrity of gasoline or diesel with required sulfur content below 30 ppm.

MTBE in gasoline

Estimates of the cost of reducing or eliminating MTBE from gasoline have been put at $1.4-10.0 billion, depending on such variables as the specific requirements for renewable-fuel content standards and maintenance of air quality benefits.

If the renewable-content standard does not require volume increases or a shift from current geographic-niche use of ethanol, the lower figure would apply for replacing lost octane and volume, while retaining the current reformulated gasoline (RFG) air toxics reduction.

But a $5 billion investment (including $3 billion for doubling ethanol production) would be required for meeting the current oxygen requirements for RFG. If MTBE is to be replaced barrel-for-barrel, ethanol production must be quadrupled, requiring a $10 million investment. The cost increase to produce RFG in this scenario is about 2.4>/gal for PADDs I and III (Table 3).

Requiring MTBE elimination within the same timeframe as gasoline sulfur reduction would place severe constraints on the permitting process and would jeopardize compliance schedules and productivity.

Driveability index

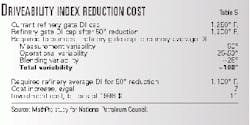

The auto industry has requested a reduction in DI (a measure of gasoline volatility), but NPC says that refiners may be required to invest as much as $11 billion to reduce the refinery gate DI cap to 1,200 degrees F., a 50 degrees F. reduction (Table 5).

Improvements in testing and operational variability might reduce total costs, and refiners are most likely to implement variability improvements.

The imposition of a more restrictive DI cap could lead to a reduction in US gasoline production.

An additional cost-benefits study is imperative before a change in DI specification should be considered, NPC emphasized.

Facilities impacts

Although existing distribution facilities can be modified to carry gasoline and diesel containing 30 ppm average sulfur, NPC found that operating costs will increase and that localized requirements may hamper cost-effective, dependable deliverability.

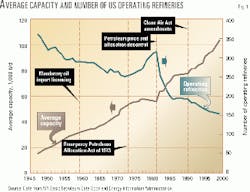

The number of US refineries has decreased at a steady rate since World War II, except for a period in the 1970s (Fig. 1). NPC expects this trend to continue, with some refineries closing and others expanding capacity to offset losses from shutdowns.

Refinery expansion is necessary to meet both demand growth and the more-stringent product quality requirements.

NPC found that reducing gasoline and diesel sulfur will require new equipment at virtually every refinery that has not yet made the transition.

US products demand

Petroleum products demand in the US tripled from about 5 million b/d in 1947, to more than 16.5 million b/d in 1999. Domestic sources provided the majority of supplies, with imports limited from nearly zero in the late 1940s to a high of 7% in the late 1980s.

Continuing increases in US light products demand are expected to average 1.9%/year between 1999 and 2005. The US refining community is expected to be significantly challenged in meeting this demand while simultaneously satisfying stringent product specification requirements.

There will almost certainly be some localized supply disruptions and price volatility, NPC predicted. And the industry's long-term capability may be reduced. In addition, some elements of the industry may employ commercially unproven technology that could yield lower costs but may represent a higher risk.

However, NPC believes short-term demand can be met if permits are granted expediently, sufficient lead time is available, and sequencing of fuel quality changes have minimum overlap.

null

NPC recommendations

NPC provided the following recommendations to help ensure a reliable supply of light petroleum products to US consumers:

- Base regulations on sound science and a thorough analysis of cost-effectiveness.

- Sequence fuel-quality changes with minimum overlap. This will help avoid delays and tight-resource scenarios.

- Complete studies before setting requirements. Significantly more study should be completed before EPA sets requirements for reducing gasoline or on-highway diesel sulfur below 30 ppm (EPA proposed in May a cap of 15 ppm on diesel sulfur [OGJ, May 17, 2000, p. 23]).

There is a significant risk of inadequate supplies should on-highway diesel sulfur levels below 30 ppm be mandated, according to NPC. By the same token, the current DI specifications should not be changed until a through analysis of the cost-effectiveness and potential impact on supply is conducted.

- Streamline the permitting process. By far, the factor having the most significant impact on the timely and cost-effective implementation of the new regulations is a prompt permitting process.

All facets of the project are built on the permitting base. The industry justifiably has concerns about the ability of regulatory agencies to review and approve the large number of necessary environmental permits in time to make required timely compliance possible.

If regulatory authorities become overwhelmed with the sheer number of permits needed, logjams will occur at the available permitting resources, resulting in engineering and construction resource constraints, higher costs, inability to meet mandated schedules, and product supply disturbances.

- Create regulatory certainty. Certainty in scope, timing, and requirements will allow the refining and distribution industries to make effective investment decisions. The EPA should clarify its position on individual state fuel requirements and eliminate uncertainty in the Tier 2 rule governing future gasoline-sulfur cap flexibility during processing unit downtimes so that refiners can plan effectively for necessary facilities.

- Promptly address environmental justice claims that arise during permitting.

- Allow offsets. Allow a portion of the emissions reduction resulting from use of lower-sulfur fuels to offset stationary source emissions resulting from new facilities required to produce the lower-sulfur fuels.

- Conduct reviews of past applications of new source reviews without retroactive reinterpretation.