Looking at Offshore Europe's prospects in a global context

Offshore Europe has seen over 30 years of continuous exploration and development activity, culminating in these record numbers: 438 fields in operation, producing about 6.5 million b/d of oil and condensate-about one quarter of the world's offshore oil output-and 20 bcfd of natural gas.

Norway and the UK together account for 88% of oil production in the region and the Netherlands 73% of its gas. But despite its large North Sea production, Europe is a net importer of both.

During 1995-99, Norway accounted for 67% of the region's new reserves that came on stream, mainly due to the start-up of Troll gas field. For 2000-04, Norway's new prospective developments are comparable to those of the UK, which accounts for nearly 50% of the reserves prospects for Offshore Europe.

In the past, Offshore Europe-the North Sea in particular-has been dominated by large fields (some delivering in excess of 400,000 b/d) and by highly productive individual wells (one in Norway's Draugen field is reported to have produced 70,000 b/d of oil).

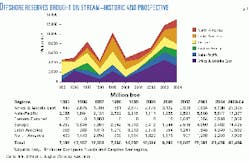

Over the past 5 years, the total worldwide oil and gas reserves bought on stream have varied greatly, with the major peaks being due to the start-up of offshore gas fields; in this respect, Offshore Europe has been the most important offshore region in the world.

Changing global picture

Looking to the future, the global offshore picture begins to change: 33% of the prospective reserves are in the Middle East (in particular the giant South Pars field); 20% in the Asia-Pacific region; 17% in Europe, which has some large prospects in 2003; and 7% in North America.

In terms of offshore production activity, Offshore Europe has been quietly going about its business, with other regions of the world grabbing headlines and commentators continually talking of the eventual decline of the region. The production of liquids and gas over the past few years have set new records not only in terms of volume, but more importantly, in increases in productivity.

Considering producing fields, Europe at 6.5 million b/d has an offshore oil production capacity second only to the Middle East. A further 0.9 million b/d is under development, and 0.6 million b/d is in the planning stage. The majority of these are likely to be tied back to the existing infrastructure as small satellite fields using subsea technology.

Looking to future prospects, Offshore Europe remains second only to the Africa-Middle East category (Fig. 1). Europe currently produces about 33% of the world's offshore gas and accounts for 23% of gas reserves under development and 20% of that currently planned for development during 2000-04. Gas production is likely to grow in light of the impending liberalization of the Euro pean gas markets and a continual shift from other fossil fuels in order to reduce emissions. In many regions, gas is regarded as the fuel of the future-none more so than Europe in 2004.

A factor favoring activity is that the marginal tax takes in some of the Northwest Europe continental shelf countries are perhaps the most attractive in the world (the UK has about a 22% take and Ireland 25%-the Irish one in particular reflecting the high costs of exploring in its deepwater Atlantic province).

Facilities

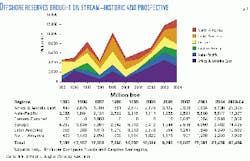

The Infield Systems database identifies 9,198 platforms installed worldwide and in prospect to 2004. Historically, most have been installed in the Gulf of Mexico, which, as shown in Fig. 2, also experienced a boom in the second half of the 1990s, then a decline as the shallow-water areas reached maturity.

Future prospects for Europe are good in terms of platform numbers, but these are mainly small units that reflect the region's mature status.

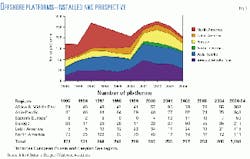

The total kilometers of pipelines installed offshore has grown from 4,531 in 1995 to 6,858 in 1999 (Fig. 3). The market has in the past been divided between three major regions of Asia-Pacific, Europe, and North America. However, in future years, the data indicates that the greatest growth may be in the Asia-Pacific and Africa-Middle East regions, as major new fields are bought on stream and large-diameter gas pipelines installed.

The market tends to split into two parts, up to 16-in. diameter and greater than 16 in. The larger diameters are usually associated with major gas trunk lines, often carrying the production of a number of offshore fields. The smaller diameters are often associated with flowlines, carrying the production of one or more wells to a platform.

The other primary segmentation is between rigid steel and flexible lines. Flexible flowlines are primarily associated with subsea well completions, where they offer the convenience of ease of lay (and recovery at end of field life), higher insulation values than steel, and greater adaptability for dynamic applications.

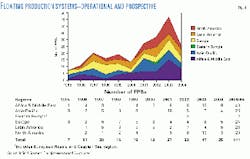

There are 41 floating production systems (FPSs) of various types operating that were installed up to 1995 and, in the past 5 years, 75 units have come into operation. But in the next 5 years, 144 are under consideration (Fig. 4). With the exception of Eastern Europe (for purposes of this study, this regional category includes Russia and the former Soviet nations bordering the Caspian Sea), the trend towards floaters is global, as in many situations, they become the production method of choice. Of those under consideration for the future, the greatest numbers of prospects are off West Africa.

There are now a substantial number of offshore installations both on the surface and subsea throughout the world. As exploration moves into ever-deeper water, subsea wells will increasingly become the preferred development option.

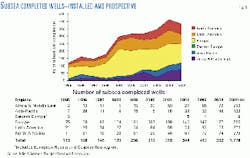

Europe has more subsea wells installed than any other region of the world (Fig. 5). Within the region, the UK has the greatest numbers of existing installations and future prospects at 419, followed by Norway at 274. Subsea well tie-backs are the most favored method of exploiting the numerous small field prospects that exist in the North Sea.

Europe is a major player in the subsea arena in the medium-term outlook, despite the growth of other regions such as West Africa and the deepwater Gulf of Mexico. However, the use of well numbers alone masks the average production rate of European subsea wells, which are significantly higher than other regions of the world. With tougher economic constraints on field developments, higher installation and maintenance costs have to be offset against greater output.

Prospects for Offshore Europe

Despite oil prices having spent several months hovering around $30/bbl, majors such as BP Amoco PLC and Royal Dutch/Shell have been basing their field development economics on $14/bbl.

At first sight, this might seem overly cautious, but a look back over the past decade shows that oil prices have averaged $18/bbl. Now there are signs that, at long last, the majors are raising their oil price expectations. In a move that might signal the real beginnings of the upturn, in late July, BP Amoco PLC CEO John Browne announced that his company had raised its oil price assumptions to $16/bbl. Although some might regard this as a small move, we believe that it is the signal to the world that oil industry activity is about to enter a period of strong growth.

In terms of Offshore Europe, a fundamental change is already under way. It is now a mature region dominated by prospects for large numbers of small fields. During 1995-99, reserves totaling 26 billion boe were bought on stream by 186 field developments, for an average of 142 million boe/field. During 2000-04, there are 315 field prospects with reserves of 14 billion boe, for an average of 45.8 million boe/field. So field development prospects are, on average, one third their previous size.

Of the 315 fields in prospect, the greatest number, 122 (39%), are being considered for development as subsea satellites. A further 100 (32%) are planned for development with fixed production platforms.

Field depletions and removal of installations is due to become a major issue in future years. During 2000-04, in theory, 111 fields will have reached the end of their life spans, resulting in 43 platforms and 163 subsea well completions requiring removal. However, in practice, this will be greatly dependent upon oil price levels and the prospects of tie-backs of new wells to existing platforms. The total cost of removal is likely to be very large, and most of it will be met by tax credits from host governments to the operators. The costs of removal of the Ekofisk structures in the Norwegian sector is estimated at 7.8 billion kroner ($850 million) by operator Phillips Petroleum Co.

Europe's competitive edge

The demand for hydrocarbons-particularly natural gas-continues to grow, and despite higher production costs than some other regions, Offshore Europe offers the very real advantages of political stability and close proximity to markets.

Offshore Europe has in the past been a high-cost region due to the impact of a harsh physical environment, overregulation, and state involvement. The historic total cost of production in the UK sector has been $13/bbl. In 2000, this is expected to fall to $10/bbl, but Southeast Asia and South America will be cheaper.

Although much faith is put in the ability of new technology to reduce offshore costs, such technology also offers the same advantage to other regions, so this factor is unlikely to give Europe any competitive edge as a production play.

In our view, there are two major factors that can give Offshore Europe a major competitive advantage:

- As long as European offshore infrastructure remains intact, it can offer the potential of cost-effective tie-backs for new small fields or "remote" pools of oil and gas in existing reservoirs. In this respect, the hasty end-of-life removal of platforms and pipelines may be shortsighted.

- Secondly, the tax system can be used to its fullest extent to encourage development of the many small fields that might not otherwise be viable when viewed against other international prospects. European governments must recognize that the potential cash-cost benefits of increasing imports of oil and gas need to be balanced against the socioeconomic benefits arising from having a local producing industry, generating not only hydrocarbons, but jobs and an industrial infrastructure that can sell oil industry technology to the developing world.

In short, Europe is a major player in the global offshore industry and, if costs can be restrained, will continue to be so for the foreseeable future. But the nature of the game has changed, and the future belongs to those operators who can offer cost effective development solutions for the sub-50-million-bbl field.

And there remains another lingering concern. The North Sea has attracted some outstanding technical and commercial innovators. The problem is that many of the service and supply companies that have resulted are locked into this single industry, oil and gas. Every industry has its cycles, and to be totally committed to a single one holds a high potential for eventual commercial disaster. Many oil service companies, as proved by the most recent downturn, need a policy of diversification into new, nonoil markets. An initiative is needed, and we offer a suggested title for it: Diversify or Die. Oil and gas is not the only offshore industry.

References

The data in this article are drawn from two sources: Infield Systems, a database containing details of existing and proposed global offshore field developments (www.infield.com); The Offshore Europe Report, which forecasts the market for Offshore Europe in a global context for 2000-04 (www.dw-1.com).

The author-

John Westwood heads the industry analysts Douglas-Westwood Associates and has, over the past 13 years, been responsible for over 120 specially commissioned oil industry business studies. He previously spent 12 years working in the underwater contracting industry and has served on the boards of offshore industry companies in the UK and Norway. His e-mail address is [email protected].