An impairment comparison of two oil price crashes

James Herr

Alvarez and Marsal

Houston

As social distancing and stay-at-home orders related to COVID-19 in March 2020 led to store and office closures and reductions in travel, it was clear that the economy would be negatively impacted. But when oil prices and stock prices began falling at a rate greater than the oil crash of 2014, a second wave of impairments was expected—by both industry and investors—to hit financial statements of oil and gas companies in first-quarter 2020 and beyond. However, the size of the impairments and the duration of the wave were uncertain.

Three quarters later there is some clarity. This article includes impairment analysis from the 2014 and 2020 oil crashes using data collected from 504 international and US publicly traded companies active in the oil and gas industry during either crash, which include companies currently operating as well as companies that went bankrupt over one or both of those periods. The companies are further separated and analyzed by industry sectors: integrated, E&P, midstream, downstream, and oilfield services.

2014 oil crash

The run up of oil prices since 2002 caused by increasing global demand and supply constraints from the US/Iraq war as well as from OPEC had been unprecedented, with prices going from under $20/bbl to over $100/bbl over the span of a decade. The global 2007-08 financial crisis led to a temporary reversal of the trend, amid concerns over the global economy’s health, but it would only take until 2011 for oil to recover to its pre-crisis pricing.

In contrast to the oil price drop in 2008, the price downturn in late 2014 was primarily a supply-driven shock, as marginal US shale producers’ continued ramp-up of oil production led to OPEC’s response to combat US shale producers with aggressive pricing in hopes of growing market share, thinking that lower prices would put US shale producers out of business. And while for the most part equity prices didn’t collapse by as much as oil or gas prices (which fell by more than 70% and 60%, respectively, from their high points in June 2014 to their low points in February 2016), the drop in price did lead to significant equity devaluation over investor concerns of prolonged market oversupply and lack of focus on cost efficiency. Figure 2 shows how oil and gas equity sector indexes other than downstream were negatively impacted by the price drops over this period, with declines ranging from 45% to 61%.

The crash led many publicly traded companies to incur substantial impairments in the energy industry globally, ranging from tangible assets such as plant, property and equipment, and oil and gas reserves, to intangible assets such as goodwill. In this article goodwill refers to accounting goodwill, which is defined similarly both for US GAAP and IFRS-reporting publicly traded companies – that is, the excess of total consideration paid for an acquired entity over the fair value of net assets acquired.

In the run up to $100/bbl oil, many companies had been working feverishly to consolidate through acquisition, leveraging both synergies and an increasing oil price to satisfy risk-averse investors, leading these companies to record sizeable amounts of goodwill, intangible asset and reserve asset values.

Figure 3 shows aggregate definite-lived tangible and intangible asset values, excluding goodwill (further referred to as Assets) by sector for publicly traded oil and gas companies from 2005 through third-quarter 2020. These Assets are primarily composed of machinery and equipment and oil and gas reserves. As some of the largest oil and gas companies, integrated companies make up a significant portion of the asset base (>60%). Oil and gas companies across all sectors saw tremendous growth in Assets from 2005 through 2013, the year prior to the 2014 oil crash, with the value of Assets more than tripling in size to $4.0 trillion at June 2014, compared to $1.3 trillion at the end of 2005.

Before discussing the magnitude of the writedowns for Assets related to the 2014 oil crash, its useful first to understand the required conditions for recognizing an Asset writedown for publicly-traded companies in accordance with financial reporting standards. International Accounting Standard Board’s International Accounting Standard (IAS) 36 and the Financial Accounting Standard Board’s Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) 360 cover the requirements for recording a definite-lived asset writedown in a company’s financial statements under International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and US generally accepted accounting principles (US GAAP), respectively. While IAS 36 covers the impairment rules for both definite- and indefinite-lived assets, US GAAP covers indefinite-lived assets such as goodwill in a separate topic (ASC 350).

Definite-lived assets are tested for impairment when a trigger event occurs, which may be when an asset’s value may no longer be fully recoverable or when the fair value of the asset is more likely than not below its carrying value. IFRS asset impairment recognition requires the carrying value to exceed the recoverable amount, defined as the greater of value in use or fair value less cost to dispose, while US GAAP more conservatively a) requires the the undiscounted cash flows over the primary asset (or asset group’s) life be less than that asset’s (or asset group’s) carrying value in order to recognize any potential impairment and b) does not allow recovery of asset value in future periods.

Based on financial reports from oil and gas companies, Figure 4 summarizes total Asset impairments by quarter and industry sector over the 2-year period beginning from the start of the price decline in June 2014. In total, Asset impairments exceeded $400 billion, with 53% of those impairments coming in the fourth quarters of 2014 and 2015. The Asset writedowns over the 2-year period represented a total reduction of 10% from the June 2014 Asset base.

Integrated and E&P companies led total Asset writedowns, representing more than 90% (59% and 32% shares, respectively) of Asset writedowns among all sampled companies. While integrated companies’ Asset writedowns alone represented approximately 59% of all Asset writedowns over the period, the integrated sector losses represented only 5% of the sector’s starting Asset base. Nearly a quarter of those writeoffs came from Petrobras, with a $17 billion writeoff in 2014 and a $12 billion writeoff in 2015 due to both graft and overvalued assets.

In comparison, E&P companies saw a loss of 27% in its Asset base, while oilfield service companies saw a loss of 12% in its Asset base. For E&P companies, the loss mainly came from lower reserve values/re-evaluations. For oilfield service companies, this related both to PP&E and definite-lived intangibles from prior acquisitions.

Similar to integrated’s small Asset writedown of their base, downstream and midstream recorded losses of only 6% and 2% off their June 2014 bases, respectively. This would be expected, given that declines in downstream asset values are generally offset by a benefit from widening crack spreads with a decline crude oil prices, while midstream is generally better shielded from impairments due to a) lower exposure to commodity risk based on fixed transportation pricing and b) longer-lived assets which at least for companies under US GAAP, make recognizing Asset impairments more difficult under ASC 360 rules.

Companies that went bankrupt in this period recognized asset impairments of just under 50% of their base over the same period, while solvent companies recognized on average an Asset writedown of 9%.

Since goodwill on a company’s books represents the excess of prior transaction prices above the value of acquired assets and for E&P companies generally the transacted price does not include any goodwill, the aggregate goodwill base was just under 5% of the aggregate Asset base in June 2014. Figure 5 shows goodwill values from 2005 through 2020 by sector. Aggregate goodwill grew by just over 8% per year between 2005 and first-half 2014, leading to a near doubling of goodwill over that period by reaching just over $160 billion by June 2014.

The midstream sector was a heavy driver of the growth in goodwill over that 9-year period, with significant growth in 2012 and again in 2014, as US shale drilling was heating up in spots like the Permian and Bakken. In fact, midstream accounted for nearly half the growth in goodwill over that period. The growth in midstream goodwill was primarily due to four large transactions: Kinder Morgan’s purchase of El Paso Corp., Energy Transfer’s purchases of Southern Union and Regency Energy and Devon Energy’s acquisition of EnLink Midstream LLC. The E&P sector saw a significant reduction of goodwill over that period, with most of that coming in 2008 with a $26 billion goodwill impairment from ConocoPhillips, related to goodwill from both its 2006 acquisition of Burlington Resources and the 2002 merger between Conoco and Phillips.

While goodwill did not appear to exhibit the same consistent run-up in values as the Assets did between 2005 and 2013, if we remove the substantial goodwill impairment by ConocoPhillips in 2008, it would exhibit a small run-up in value between 2005 and 2013, albeit still with a substantially smaller annual compound annual growth rate (CAGR) than that observed for the Assets.

In contrast to Asset writedowns, financial reporting for goodwill (and other indefinite-lived intangible assets) impairments are covered under US GAAP’s ASC 350 and IFRS’ IAS 36. Under ASC 350, the amount of goodwill impairment would be determined by the excess of the carrying value over the fair value of the reporting unit, up to the total amount of goodwill on the balance sheet. Under IFRS, goodwill impairment would be determined by the excess of the carrying value over the recoverable amount of the cash generating unit, also up to the goodwill balance.

Figure 6 summarizes total goodwill impairments by quarter and sector over the 2-year period beginning from the start of the price decline in June 2014. In total, goodwill impairments over that period exceeded $45 billion, representing a reduction of 30% off the existing goodwill base at the end of June 2014. E&P and oilfield services combined for 68% of all goodwill impairments over the period (at 33% and 35%, respectively). However, E&P’s smaller goodwill balance (based on write-offs in 2008) led to elimination of more than 62% of E&P existing goodwill balances, while oilfield services’ impairments only removed 43% of its starting goodwill balance. Downstream was the least impacted, with a 2% share of total oil and gas companies goodwill impairments, which led to just an 8% reduction of downstream’s starting goodwill value base.

2020 oil crash

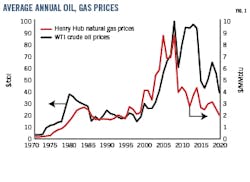

After reaching a low of nearly $26/bbl in February of 2016, the WTI crude oil price had since recovered to float around an average price of $60/bbl up through the beginning of 2020. But as Figure 1 shows, the oil price started declining in January 2020, due to the coronavirus’ impact on the global economy, exacerbated by global price war between OPEC and Russia in March 2020. Oil prices fell from a high at the end of January of just over $63/bbl to a low of $21/bbl at close on Friday, Apr. 17. By Monday, the oil price for the next month’s (May) delivery dropped to nearly negative $40/bbl before returning positive by day’s end. At the end of June 2020, the WTI price was still below $40/bbl. In contrast to the 2014 crash, natural gas prices didn’t suffer as much, falling from a Dec. 4, 2019, closing price of $2.43/MMbtu to a March close low of $1.70/MMbtu, a drop of just over 30%.

As shown in Figure 7, equity prices for publicly traded oil and gas companies declined more consistent with oil prices than with gas prices. The equity prices of the companies fell between 50% and 70% at its worst in March 2020, then recovered a portion of that loss afterwards, but at the end of June 2020 were still off from their December values by more than 35%.”

In contrast to the 2014 oil crash, where Assets had been growing at a CAGR of 14% per year, the growth in the Asset base for oil and gas companies had slowed in the run-up between 2015 and the 2020 crash, with Asset values growing by only 5% per year over that period (Figure 3).

Goodwill, on the other hand, grew faster after the 2014 oil crash, with a CAGR from 2016 through 2019 of 11% compared to just 8% prior to the 2014 oil crash (Figure 5). While some of that was due to the lower goodwill base after heavy goodwill impairments in 2014 and 2015, the larger driver came from midstream transactions, driven by the new TCJA tax rules making limited partnerships and LLCs a less-favorable entity structure relative to a C-corp structure. Notable midstream acquisitions included Enbridge’s acquisition of Spectra Energy and MPLX’s acquisition of Andeavor Logistics LP.

Figure 8 shows Asset writedowns between fourth-quarter 2019 and third-quarter 2020. Impairments nearly doubled from fourth-quarter 2019 to first-quarter 2020, and then declined to unremarkable amounts in third-quarter 2020. E&P and integrated companies shared nearly equally the impairment losses compared to total impairments, representing 88% of all impairments over the four quarters shown.

In looking at the magnitude of impairments between the two crashes, first-quarter 2020 impairments exceeded fourth-quarter 2014 impairments by over $20 billion, with a greater share of E&P companies impairing assets in first-quarter 2020 relative to fourth-quarter 2014.

In second-quarter 2020, Asset writedowns reached $60 billion, with almost 30% of those impairments related to BP’s $17.5 billion write-down associated with its lower oil price forecast and COVID-19-adjusted outlook. Interestingly, Asset writedowns declined substantially in third-quarter 2020 compared to prior quarters, which is inconsistent with the pattern observed in the 2014 crash. For the 2014 oil crash as seen in Figure 6, the fall-off in Asset writedowns from first-quarter 2015 to second-quarter 2015 was small, while the fall-off from 2020 second quarter to 2020 third quarter was substantial, as shown in Figure 8. This would indicate that many companies tended to impair assets earlier, likely due to the sharper drop in oil prices in the 2020 oil crash relative to the 2014 oil crash.

Assuming a similar pattern with the one observed in the 2014 oil crash and a continued low oil price environment, we will likely see another uptick in impairments in fourth-quarter 2020 for Asset impairments that may exceed $100 billion. Exxon said in fourth-quarter 2020 that it expects an asset impairment at yearend 2020 of up to $20 billion, with Shell following up with an announced $4.5 billion in additional asset impairments from prior quarters. However, the introduction of COVID-19 vaccines and OPEC+’s December decision to restrainedly increase production by 500,000 b/d in January 2020 may lead to reduced impairments for the quarter.

Figure 9 summarizes total goodwill impairments by quarter and sector over the four quarters from fourth-quarter 2019 through third-quarter 2020. In total, goodwill impairments over the period exceeded $58 billion, representing a reduction of 22% off the existing goodwill base from the end of third-quarter 2019. Most of those impairments were incurred in first-quarter 2020, with oilfield services making up 43% of total impairments, while midstream came second, with 26% of total impairments over that period. Despite the 22% reduction in the goodwill base, at the end of third-quarter 2020, goodwill on oil and gas sector publicly traded companies’ books still totaled more than $161 billion, which, if we observe a similar pattern to the 2014 oil crash, would indicate another wave of yearend goodwill impairments for most sectors.

Looking at companies that declared bankruptcy, a similar number of operating publicly-traded bankruptices was observed when comparing the 2014 crash to the 2020 crash (just over 20) despite the first crash period being twice as long as currently observed for the second crash period. Bankrupt companies in both crashes tended to impair their assets (both for Assets and for goodwill) nearly twice as much as non-bankrupt companies.