Crude exports, gas imports possible development path for Mexico

John McNeece

Center for US-Mexican Studies

San Diego

Veronica Irastorza

NERA Economic Consulting

Mexico City

Mexico should consider focusing its exploration budget on crude oil while expanding natural gas imports from the US. Mexico’s imports of US gas have already grown dramatically, driven by high demand based on increasing use of natural gas as a fuel for electricity generation and declining supply in Mexico as well as ready availability and low prices of natural gas from the US. In fact, Mexico’s electricity system relies mostly on gas, more than 29 Gw of natural gas plants generating more than half the country’s power. Furthermore, Mexico’s government has announced the construction of five new combined cycle gas turbine (CCGT) plants.

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador proposes to reduce imports by increasing Mexico’s domestic production of natural gas. As one of the few energy goals in President López Obrador’s National Development Plan 2019–24, Mexico’s domestic production of primary energy, which includes natural gas and other raw sources of energy, is set to cover 100% of consumption by 2024, up from the current level of 70%.

It is not clear, however, that President López Obrador will be successful in growing Mexico’s gas production, considering state Petroleos Mexicanos’s (Pemex) inadequate exploration and development (E&D) budget for 2019 and President López Obrador’s announced policy against using fracking to extract natural gas.

This uncertainty means that Mexico will continue to rely on the US for its natural gas supply. Based on this assumption, there has been substantial expansion of both the cross-border gas pipeline network and Mexico’s domestic pipeline network. US forecasts indicate there will be plenty of gas available for export to Mexico at prices increasing only gradually from existing lows.

There is political risk involved in dependence on the US for natural gas, but there is a low probability Mexico would face a cutoff or cutback of gas from the US, considering the benefits accruing to US producers from sales to Mexico and US political, legal, and treaty barriers against such action.

Mexico could reasonably rely on imports of natural gas from the US while it tries to expand its own production. Mexico also could decide to focus on increased production of crude oil, which garners high prices in the world market, while relying on the US for most of its natural gas.

Rising consumption

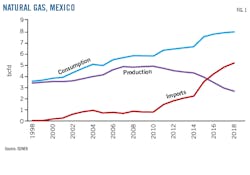

According to data from Mexico’s Secretaría de Energía (SENER), shown in Fig. 1, Mexico’s consumption of dry natural gas grew substantially between 1998 and 2018, reaching 8.1 bcfd. But production failed to keep pace with demand. Imports made up the difference, reaching 5.4 bcfd in 2018. Most of these imports came from the US.

After 2010, natural gas production declined while consumption grew significantly, driven mainly by the electricity sector’s replacement of fuel oil with gas. Mexico’s Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos (CNH) reported in September 2018 that if existing trends continued, Mexico would import 94% of all natural gas consumed in the country by 2030.

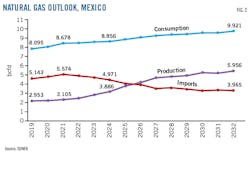

Under the previous administration, SENER projected Mexico would reverse this trajectory. Under a maximum production scenario, as set forth in its “Prospectiva de Gas Natural 2018-2032” (Fig. 2), SENER anticipated an aggressive turnaround, with an increase in production over the period 2019-32 and a corresponding reduction in imports.

Under SENER’s projections, production would grow rapidly from 3 bcfd in 2019 to 6 bcfd in 2032, a 100% increase. Consumption grows more slowly over the same period, to 9.9 bcfd from 8 bcfd, or 23%. By 2032 imports would decline to 4 bcfd.

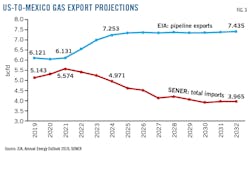

But the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) does not agree with this scenario. Fig. 3 shows EIA projections for natural gas exports via pipeline from the US to Mexico as compared with SENER projections for total imports.

EIA pipeline export projections are higher than SENER’s total import projections for each year in the period, with a growing differential over time. EIA pipeline export projections reach 7.4 bcfd in 2032, 88% higher than SENER’s total import projection of 4 bcfd for the same year.

EIA export figures are so much higher than the corresponding SENER numbers primarily because EIA anticipates significantly lower Mexican production of natural gas than SENER. Projections are inherently uncertain, but the large differential between EIA and SENER figures on US pipeline exports and Mexican total imports raises the question of whether Mexico can increase natural gas production above the downward-sloping historical trend as quickly as SENER projected.

SENER’s “Prospectiva 2018–32” was issued in November 2018, under the administration of Enrique Peña Nieto. President López Obrador has proposed his own National Hydrocarbons Production Plan, which contemplates growth in natural gas production over the course of his six-year term to levels even higher than those in SENER’s maximum production scenario.

At the same time, however, López Obrador seems to want that growth to occur without private participation. To that end, he cancelled the upcoming 3.2 and 3.3 bid rounds, both in Burgos basin, which would have been open to foreign investors. Round 3.2 sought bids for onshore blocks targeting mostly conventional natural gas. Round 3.3 targeted blocks of unconventional gas resources and was going to be the first bid for unconventional resources in Mexico.

President López Obrador has made it clear that he plans to reinvigorate Pemex and, through Pemex, Mexico’s hydrocarbon sector. This is a key part of his strategy of energy sovereignty. It will be Pemex’s responsibility to increase production of oil and natural gas. With respect to oil, President López Obrador has set a goal of increasing production from the 1.7 million b/d recorded at the end of 2018 to 2.7 million b/d by end-2024.

López Obrador has not set a specific goal for dry natural gas production. Under his strategy of energy sovereignty, however, there is an implicit goal for Pemex to increase production from the 2.8 bcfd recorded in December 2018 to a figure closer to projected 2024 demand of 8.9 bcfd. But Pemex will face severe budgetary issues in meeting these goals if it seeks to do so without the benefit of outside investment.

Pemex Exploración y Producción (PEP) will receive 210 billion pesos ($11 billion) under its 2019 budget for exploration and development of new hydrocarbon resources, covering both oil and gas. PEP will also receive tax benefits in the form of an 11 billion peso increase in the limit to the deductions it can take against its taxable income, giving it a total of 221 billion pesos for exploration and development. According to the Comisión Reguladora de Energía (CRE), however, PEP needs 406 billion pesos, nearly twice the budgeted amount, just to pursue the drilling areas assigned to it in Round Zero of the hydrocarbon auctions that took place under Peña Nieto.

Another way to look at the adequacy of Pemex’s exploration and development budget is to compare it and the corresponding performance goals with the expenditures and performance of other oil and gas exploration and production (E&P) companies.

The five largest US E&P companies by market capitalization (as of May 9, 2019)—ExxonMobil, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, EOG Resources Inc., and Anadarko Petroleum—collectively produced 2.56 million b/d of oil and NGL in 2018, and 6.2 bcfd of dry natural gas, solely from US operations, in each case roughly comparable to Pemex’s goals for 2024. The average aggregate E&P budget for these five companies on an annual basis over the period 2016–18 was $21 billion, or 1.9 times the $11.6 billion budgeted for Pemex E&P for 2019. The five companies spent an aggregate of $29.2 billion on E&P for US operations in 2018, 2.6 times Pemex’s 2019 E&P budget.

The E&P figures shown for the five companies are based on aggregate costs incurred by those companies for exploration and development for US operations only, as shown in the companies’ 2018 10-K securities filings, adjusted for comparison purposes to exclude costs for acquisition of rights to hydrocarbons in the ground since Pemex does not pay for such rights, which are owned by the Mexican state.

Even without evaluating the relative efficiency of Pemex versus the other five companies, these comparisons suggest that the $11.6 billion 2019 E&P budget for Pemex is insufficient to reach the goals that have been assigned to it. A reasonable benchmark for Pemex E&P expenditures going forward would be the $29.2 billion the five identified US companies invested in E&P for their US operations for 2018. But this is an enormous number.

The total amount Pemex paid to the Mexican government in 2018 as profit sharing tax (DUC) was $24.7 billion (470 billion pesos). For Pemex to have $29.2 billion annually for E&P, the Mexican government would need to give up the DUC as a revenue source, probably resulting in increased taxes on other economic actors. The government would also need to make contributions into Pemex from other revenue sources. This would be problematic for the Mexican state.

Another constraint on increased gas production is President López Obrador’s rejection of fracking. Fracking has had a striking impact on the US oil and gas industry, leading to huge investment in exploration in fields such as Eagle Ford and the Permian basin, and a significant increase in oil and gas production. Seventy percent of natural gas produced in the US now comes from fracking.

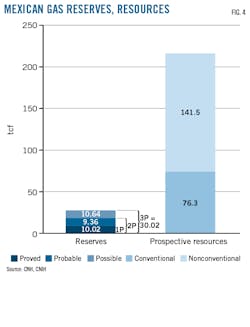

Most of Mexico’s prospective hydrocarbon resources are non-conventional, which would require fracking to exploit. Fig. 4 shows Mexico’s proven, probable, and possible reserves of natural gas (commercially viable gas deposits, at different levels of probability of recovery), as well as prospective resources (potentially recoverable gas deposits that are not commercially available due to the absence of ongoing projects).

In evaluating these numbers it is important to note that gas from non-conventional prospective resources requires fracking to release the gas from the rock that holds it. Accordingly, all prospective natural gas resources shown as non-conventional in Fig. 4 cannot be recovered without fracking. If Mexico rejects fracking as a production tool it will find it difficult to increase natural gas production, especially given that production over the last several years—derived primarily from conventional sources—has already been declining.

Mexico will continue to rely heavily on the US for its natural gas supply. The US Department of Energy (DOE) forecasts that there will be plenty of natural gas in the US available for export to Mexico. According to the “Annual Energy Outlook 2019 with projections to 2050” (AEO 2019), prepared by the EIA, US natural gas production will continue to exceed domestic demand for the foreseeable future, allowing for exports. There is also a large and growing network of cross-border pipelines that would facilitate increased exports of US natural gas into Mexico.

If Mexico relies on US natural gas, it will be subject to market prices for its purchases from the US and therefore subject to price volatility. But according to AEO 2019 and a separate DOE study regarding the impact of increased US exports of LNG on US natural gas prices, forecast price increases would be gradual and modest.

A degree of political risk also exists if Mexico continues to rely on the US for its gas. An impulsive US president like Donald Trump could try to bully Mexico with threats of a cutoff or cutback of US natural gas if Mexico does not do as it is told. But President Trump does not control the US natural gas industry, which is made up of many private companies with substantial resources and strong political connections.

President Trump would face serious political resistance if he tried to use natural gas as leverage against Mexico. The US natural gas industry earned $6.4 billion from natural gas sales to Mexico in 2018, a figure likely to increase in future years, and US producers would strongly contest the loss of this revenue. US producers would also be concerned that reduced natural gas sales to Mexico would lower US domestic gas prices for all producers. In 2018, US exports of natural gas to Mexico constituted 6.1% of total US production of dry natural gas and 52% of US dry natural gas exports. Reduced exports to Mexico would mean that US production of natural gas would further exceed demand, driving down prices. Legal and international trade limits also exist that would reduce the effectiveness of any effort to restrict the export of US gas to Mexico

The risks Mexico assumes by counting on the US for a substantial portion of its natural gas needs are manageable. Mexico could reasonably rely on imports of natural gas from the US while it tries to expand its own production. Complementing an effort to increase production, Mexico could also seek to reduce consumption through increased use of renewables.

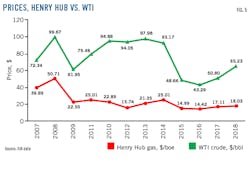

Mexico might also consider whether it should focus its efforts on increased production of crude oil while relying on the US for its natural gas needs. In US gas markets adjacent to Mexico the BOE price of natural gas has historically been much lower than crude oil. Fig. 5 shows the 2007-18 benchmark spot price at Henry Hub for natural gas as compared with the benchmark spot price per barrel for West Texas Intermediate crude oil.

These prices suggest Mexico could benefit economically by directing its limited exploration and development budget to the production of crude oil for sale at higher prices while purchasing natural gas from the US at lower prices. Mexico’s direct access to the US natural gas market makes this feasible. Mexico would still need to produce its own natural gas for those areas of the country that cannot obtain US gas at a low price, particularly in the south of Mexico, as well as for the manufacture of petrochemicals, which depend on the natural gas liquids included in raw natural gas and removed from the dry gas delivered from the US. But associated gas produced with the crude oil would be available for these purposes. Mexico could also selectively explore for domestic natural gas to supply its south while still allowing some shift of Pemex’s E&P budget toward oil.

The authors