US sanctions threaten Iran’s oil exports, production

Sara Vakhshouri

SVB Energy International

Washington

Iran’s energy industry started 2018 full of hope for growing oil production and exports. But risks abound, including new US sanctions, a possible global alliance against Iran’s alleged support of rebels in Yemen, and protests within Iran.

An international agreement called the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) of 2015 lifted international sanctions against Iran. JCPOA included China, France, Germany, Russia, UK, US, and the European Union (EU).

Iran promised to limit its nuclear program in return for relief from economic sanctions. But US President Donald Trump on May 8 announced a US withdrawal from the agreement.

Table 1 shows the degree to which Iran has increased oil production since sanctions were lifted. Despite new sanctions, Iran possesses the technical capability to increase oil and natural gas production further.

The US withdrawal likely will not have an immediate effect on Iran’s oil exports.

US sanctions alone will not be as effective as in 2012. Effective oil export sanctions require participation of at least one major buyer. Iran has attained a high oil market share in the EU since JCPOA. EU officials say they likely will continue importing oil from Iran regardless of Trump’s foreign policy.

Separately, the war in Yemen creates conflict between Iran and Saudi Arabia, potentially threatening oil flow across the Middle East if tensions escalate.

Iranian oil and petrochemical production also potentially could be threatened by the country’s largest civil unrest since 2009. Demonstrators took to the streets in Mashhad on Dec. 28, 2017, protesting the cost of living. The protestors were mostly from lower income brackets. Unlike previous widespread protests in Iran, no specific group is leading the latest demonstrations.

Trump, JCPOA

Iran faces two sanctions, one on oil imports and one on investment. Refiners have 180 days to reduce their imports of Iranian oil. Most international investors delayed engaging in oil and gas contracts in Iran, awaiting the Trump administration’s decision on sanctions.

In October 2017, Trump decertified Iran’s compliance with JCPOA. The EU and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) say Iran has complied with JCPOA’s terms.

Regarding Iran’s association with Yemen rebels who launch missiles at Saudi Arabia, the UN has found Iran to be in noncompliance with a ban on supplying arms to Yemen. A report to the UN Security Council earlier this year said investigators studied missile debris and military equipment in Yemen they believe to be from Iran.1

The 329-page UN report said inspectors “identified missile remnants, related military equipment, and military unmanned aerial vehicles that are of Iranian origin and were brought into Yemen after the imposition of the targeted arms embargo.”

Iran denies the report’s conclusions although US Ambassador Nikki Haley has said the report identifies Iranian weapons and ballistic missiles introduced into Yemen.

Houthi rebels in Yemen have repeatedly launched missiles at Saudi Arabia, including missiles fired at Riyadh in October 2017. Saudi officials said they intercepted most of those missiles.

Some political observers believe the missile launches encouraged new US sanctions on Iran.

“We see [the missile launch] as an act of war,” Saudi Foreign Minister Adel Jubair told CNN. “Iran cannot lob missiles at Saudi cities and towns and expect us not to take steps.”

French President Emmanuel Macron blames Iran for providing missiles to Yemeni Houthis. In November 2017, Macron said: “The missile [launched at Riyadh]…obviously is an Iranian missile” and demonstrates Iran’s ballistic activities.

The Iranian government increased security after the missile launch, expecting a potential counterattack in retaliation for the Houthi launch. No such attack had occurred as of early May.

Next steps

US and EU officials failed to find middle ground to renegotiate JCPOA, which SVB Energy believes was Trump’s desire from the beginning. Among EU members, France was the most critical of Iran’s missile program.

EU is encouraging Iran to follow JCPOA’s terms and stay in the agreement.

Separately, Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev signed an interim agreement in April to establish a free trade agreement between Iran and members of the Eurasian Economic Union. Medvedev suggests Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia could offer tariff concessions to Iran.

Many international investors are increasingly concerned about the Iranian-Saudi conflict. Some also are concerned EU allies could renew an international alliance against Iran.

SVB Energy believes EU’s policy position might get closer to Trump’s position if Houthi missile launches to Saudi continue.

Since the JCPOA, only French company Total SA had signed an upstream contract with Iran. Total on May 16 said it may withdrew from its South Pars Phase II development contract, which includes a force majeure clause allowing Total to exit without penalty in case of international sanctions.

Iranian officials made sure this clause applied only to an international sanctions alliance and not US unilateral sanctions.

Saudia Arabia also incentivized Total’s withdrawal from Iran by signing a $44 billion downstream joint venture between Saudi Aramco and Total in India.

Iran protests

The 2017 protests quickly spread across Iran. Unlike previous demonstrations involving urban, middle-class residents having political grievances, these demonstrations involved rural, poor Iranians upset with their financial status.

As of early January, more than 22 people had died in the street demonstrations and authorities had arrested thousands. Protesters cited economic grievances such as a high unemployment rate, government corruption, and price surges for basic goods, including groceries.

Critics have attacked Iran’s top officials: Supreme Ayatollah Sayyed Ali Khamenei, Iran President Hassan Rouhani, and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard for alleged corruption, poor policies, and focusing on world conflicts instead of Iran’s economy.

Power struggles among political groups within Iran also are behind the unrest. Other contributing factors are external. Iran-Saudi tensions have surged since Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman assumed power in Saudi Arabia, bringing a lack of trust and a new Saudi security strategy.

In May 2017, bin Salman said, “We are a primary target for the Iranian regime,” and he accused Iran of seeking to take over Islamic holy sites in Saudi Arabia. “We won’t wait for the battle to be in Saudi Arabia. Instead, we’ll work so that the battle is for them in Iran.”

Since then, Iranian fields and associated infrastructure experienced various incidents, including explosions. Iranian officials consequently increased security.

The protests spread to southern cities hosting major oil fields, ports, and refineries. Iranian government and security forces have since secured oil and gas fields, ports, refineries, and petrochemical and power plants.

Sabotage remains a risk to Iran’s oil infrastructure, which remains vulnerable to possible destructive acts by its own workers. Most oil workers are low paid.

Southern Iranians long have complained about poor economic conditions. Air pollution and water pollution compound the grievances. The discontent extends beyond Sunnis and Arabs to Persians and Shiites.

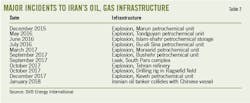

SVB has tracked about 40 suspicious incidents since December 2015 affecting Iran’s oil and gas fields and infrastructure. Causes of the incidents are unclear but Iran has no prior history of such a consistent series of incidents.

Whether foreign attacks, domestic sabotage, or technical errors caused these incidents, the outcome is the same: interruption of Iran’s energy supply. Interruptions will persist unless causes are clearly identified and addressed.

Iran’s Central Oilfield Co. took almost 60 days to extinguish a fire ignited by an October 2017 explosion on a rig drilling Well 147 in Ragsefid field.

Iranian officials also fear cyber-attacks on oil and gas operations from outsiders hoping to benefit from Iran’s domestic instability.

Table 2 shows the most significant incidents affecting Iran’s energy centers, including an explosion in a Tehran refinery and also a supply interruption to South Pars condensate production.

Government officials blamed the refinery explosion on leaking products. Consequently, 40,000 b/d of production from South Pars was temporarily shut in.

Separately, NIOC executives blamed a leak for cutting condensate production in late 2017. The leak’s location was not announced, but Iran’s condensate exports dropped by 150,000 b/d during September-December 2017 due to a domestic demand surge at the Persian Gulf Star refinery.

NIOC cut South Pars condensate term allocations to export buyers for second-quarter 2018, saying the condensate was needed for the Star refinery, Platts reported in March.

Exports of Iranian crude to South Korea, a major buyer of South Pars condensate, tumbled during the first 2 months of 2018, totaling 9.088 million bbl, 32% less than the total through February 2017, Platts said, citing Korea National Oil Corp. statistics.

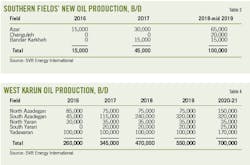

Table 3 shows new crude oil capacity that will be added from Iran’s southern fields. Investment is in place for additional production increases in 2018-19 but such plans could be affected by sanctions and a ban on oil exports.

Production capacity

If sanctions mean Iran cannot maintain and increase its exports, it will have to reduce production. Priority would be placed on continuing light crude oil production from West Karum oil fields. The southern heavy oil fields would be where production likely would be cut with new sanctions. Iran’s production had surged after sanctions were lifted in January 2016,

Output rose to more than 3.5 million b/d in May 2016 from less than 2.9 million b/d in late 2015. Output averaged 3.79 million b/d in the first half of 2017 and about 3.8 million b/d in the second half.

Iran is expected to use improved oil recovery (IOR) to maintain current production in its southern oil fields despite high natural decline rates. With sanctions lifted, these core regions rapidly increased output, mostly due to IOR. The southern fields quickly increased output by 500,000 b/d in first-half 2016.

Iran started preparing to increase production after the international agreement was announced in June 2015. Production then increased in January 2016 upon removal of the export ban.

In 2017, production grew by about 45,000 b/d. Production capacity of the southern oil fields is expected to rise another 55,000 b/d by June 2019.

Less developed fields also contribute to increased production. Table 4 shows most of Iran’s new oil production will come from the recently developed West Karun fields where production averaged 260,000 b/d in 2016, up from 100,000 b/d in 2015. Peak West Karun production during 2016 reached 280,000 b/d for the month of October.

Production reached 345,000 b/d by December 2017 and is expected to reach 380,000 b/d by mid-2018.

With no interruptions, Iran could increase production 180,000 b/d by mid-2019, of which 125,000 b/d would be from West Karun oil field and the rest from southern oil fields. If Iran’s upstream projects proceed as planned, production could reach 550,000 b/d by the late 2019 and 700,000 b/d by 2021.

Additional sanctions

A unilateral US effort will be less effective than an international alliance. EU’s previous ban on importing Iranian oil served as a foundation for coordinated sanctions that directly targeted Iran’s oil revenues and effectively reduced its exports. Anticipated oil price shocks were avoided in 2012 because other factors, such as rising US shale production and Saudi oil production, helped balance the market.

The EU repeatedly has affirmed its JCPOA support, saying sanctions would violate JCPOA’s intentions because Iran is complying with it.

Asian buyers started searching for substitute suppliers in case of new sanctions on Iran’s oil exports. The US-EU sanctions of 2012-15 excluded condensate, but new US sanctions likely could include condensate.

The pending reduction in Iranian oil imports is expected to begin with South Korea and Japan. China and India will try to gradually cut Iranian imports.

Asian buyers are looking to Norway as a substitute condensate provider. Iran, meanwhile, has prepared for possible sanctions by offering options such as receiving payments in the local currency of non-US countries to potential importers.

In April, Iran raised its exports to the highest since January 2016. By increasing its export volume, Iran could have slightly minimized the consequences of Trump reimplementing US sanctions.

The April export figure could be the measurement that US officials use for refiners’ import-reduction requirements.

EU refiners also have started looking for alternate sources in case Iran exits JCPOA or in case of renewed US-EU sanctions on Iran’s missile program.

It is important to consider a scenario by Nov. 4 in which tensions escalate in Yeman and Syria. The EU could decide to follow US sanctions on Iran. If this scenario happens, SVB Energy expects full EU support of US sanctions on Iran, making sanctions more effective.

References

1. Panel of UN experts on Yemen final report to UN Security Council, Jan. 28, 2018. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1GcS0FtU5FDqowTs7owVxdYJHuN9mPVvl/view

The author

Sara Vakhshouri is founder and president of SVB Energy International of Washington, DC. She has extensive experience in global energy market studies, energy security, and geopolitical risk with a special focus on the Middle East, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Mexico. Vakhshouri previously worked for both private and public Iranian energy companies, including the National Iranian Oil Co., during 2000-08. Vakhshouri has advised numerous energy and policy leaders, international corporations, think tanks, investment banks, and law firms on the global energy market, the geopolitics of energy, and investment patterns.