Outlook for US gas supply improves if production efforts are stepped up

This is an update of a recent article by the author in which he painted a rather pessimistic picture of the future of US natural gas production based on the Potential Gas Committee’s Dec. 31, 2004, report.1

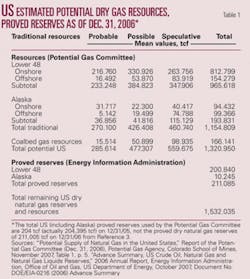

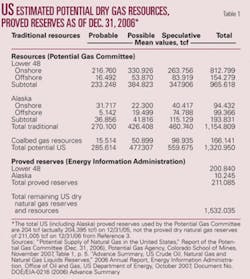

The new total remaining dry gas resource volume of 1,320,950 tcf on Dec. 31, 2006, estimated by the PGC2 represents an increase of 201.695 tcf from the Dec. 31, 2004, value in spite of a decrease in the coalbed methane value.2 To the end-2004 resource must be added the end-2004 proved reserves of 192.513 tcf.

As noted on Table 1, the PGC in its end-2006 estimate of remaining US dry gas reserves and resources of 1,525 tcf used an obsolete end-2005 value of 204 tcf for its estimate of total remaining dry US gas supplies (actually 204.385 tcf) instead of the end-2006 value of 211.085 tcf (Lower 48 states 200.840 tcf plus 10.245 tcf in Alaska.3) Thus, the corrected end-2006 value of potential US gas resources and proved reserves is 1,532.035 tcf.

Future US production

In order to arrive at an estimate of how much US gas remains for future production, cumulative production through the end of 2006 must be added.

In its Dec. 31, 2006, report, the PGC estimated this value at 1,091 tcf on Table 5, p. 8,4 or a total original resource base using the corrected value for end-2006 proved reserves of 2,623 tcf.

Assuming that total US dry gas production follows an symmetrical inverted bell-shaped (sigmoidal) curve as originally proposed by the eminent geologist M. King Hubbertwho correctly projected US peak crude oil production by this method1the peak in total US dry gas production would occur when one-half, or 1,311.5 tcf, have been recovered.

Subtracting the 1,091 tcf already produced leaves only about 221 tcf before production would plateau.

At projected dry gas production levels of 19.35 tcf in 2010 and 19.60 tcf in 20155 we would have 11.3 years of slightly rising production levels remaining unless an all-out effort is made to tap what are believed to be vast remaining conventional and unconventional (tight formations, Devonian shales, and coalbed methane) resources.

The latter seems likely as discussed below. This does not even include the potentially enormous resource of more than 100,000 tcf of methane locked in hydrates in nine US coastal plays and one small Arctic onshore play in Alaska.

Worldwide needs

In view of the importance of gas with an carbon to hydrogen atomic ratio of 1:4 compared with 1:2 for oil, 2:1 for coal, and 10:1 for wood as the obvious transition fuel to a carbon-free US and global energy system and the encouraging 2007 report by the PGC, a stepped-up US and global effort to increase gas production is clearly indicated.

This requires first of all more US and international pipeline capacity, notably from Alaska to the Lower 48 states, more Russian Gazprom pipelines to Europe and a new pipeline to China, and a continued increase in liquefied natural gas production, tanker transport, and receiving and gasification facilities in the US, Europe, India, and China.

In addition, it calls for a serious effort to develop the methane hydrate option globally to recover a significant portion of the roughly 700,000 tcf of methane locked largely in coastal deposits and in terrestrial deposits in subarctic regions such as Siberia.6

In Table 2, the encouraging data of US reserve replacement from 1994 through 2006 are summarized. It is an update of Table 6, Parts 1 and 2, in a recent article by the author7 and shows the US exploration and production industry’s remarkable ability to more than replace dry gas production with reserve additions.

From 1994 through 2006, only in 1998 was the value below 100% (83%). In all other years, reserve replacement exceeded gas production by as much as 131% to 163% (2005). In connection with the encouraging 2005-06 PGC biannual report summarized in Table 1, this offers great promise that the US will be able to meet its consumption needs for at least 11 years as noted above, although that is not nearly enough if current US power generation by inefficient (about 30-35%) coal-fired steam-electric plants were to be replaced by efficient (60%) gas-fired combined cycle plants to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by two-thirds as discussed in detail in Reference 7.

It therefore seems imperative to develop and commercialize Integrated Coal Gasification-Combined Cycle (IGCC) plants modified with a catalytic water gas shift step with more steam (CO + H2O " CO2 + H2) of the raw synthesis gas and removal and sequestration of the CO2 in suitable underground formations to produce a more than 90% pure hydrogen stream for efficient combined-cycle power generation or as a source of hydrogen for fuel cell-powered surface transport.

In Table 3, US gas supply and consumption data (historical for 2003 and 2005 and projections to 2030) published by the Energy Information Administration are summarized.8 Table 3 shows a peak in dry gas production of 20.79 tcf in 2020, slightly more optimistic than the projection based on the Hubbert methodology discussed earlier.

It can be seen that net pipeline imports and imports will decrease from 3.01 tcf in 2005 to 0.92 in 2030 and that LNG imports will rise only modestly from 0.57 tcf in 2005 to 4.53 tcf in 2030 due to resistance to the construction of new receiving terminals in the US and global competition for supplies. This further increases the urgency of increasing domestic production of gas, including serious pursuit of the methane hydrate option.

The importance of Russia in the global gas supply system is summarized in Table 4 received in a private communication from Pace Global Energy Services in Washington, DC. Russia is the largest gas reserve holder with 1,680 tcf as of Jan. 1, 2006, out of a total of 6,182.7 tcf,9 or 27%.

Gazprom is the major player in the Russian gas industry and the major source of supply for much of Europe and the countries of the Former Soviet Union. Of special importance would be the construction of a pipeline to China for power generation to reduce its dependence on coal.

Returning to the prospects of the role of unconventional gas production in US gas supply, there is general agreement that it will provide about 10 tcf from the Lower 48 states to supply a total of roughly 20.5 tcf in 2030.5 A recent article by Vello A. Kuuskraa et al.10 makes a detailed analysis of how this volume might be increased.

Nevertheless, it seems increasingly clear that US gas supply, except possibly for LNG imports, will reach a plateau around 2030, unless the positive outlook for increased unconventional gas production is realized.

Outlook

In view of the limitations on US gas supply as a transition fuel to a sustainable energy system which will require 30-50 years, it is clear that we must accelerate the commercialization of the gasification of coal and lignite, the most abundant US and global energy resource, into hydrogen and synthesis gas for the production of synthetic liquid fuels and methane using technologies which permit the removal and sequestration of most of the CO2 formed.

Sustainable energy systems by definition use inexhaustible and emission-free energy sources such as solar photovoltaic and solar thermal power and wind and hydroelectric power whose availability is limited and which also have some negative environmental impacts.

In addition, the research, development, and demonstration on environmentally benign and economically feasible recovery of methane from the vast US and global resources of methane hydrates must be accelerated. The apparently insurmountable limitations on the use of biofuels as a major sustainable energy source to replace fossil fuels are beyond the scope of this article and have been discussed by the author in two earlier articles and widely in the energy press.1 11

Acknowledgment

Thanks are due to the Potential Gas Committee of the Potential Gas Agency, Colorado School of Mines, for making its new Dec. 31, 2006, assessment of potential and proved gas resources and reserves available for this update of future US gas supplies, and to Pace Global Energy Services of its analysis of Gazprom as a source of gas supply for the FSU, much of Europe, and potentially China.

References

- Linden, H.R., “Global oil, gas outlook bright; US gas production nears plateau,” OGJ, Vol. 104, No. 44, Nov. 27, 2006, pp. 20-28.

- “Potential Supply of Natural Gas in the United States,” report of the Potential Gas Committee (Dec. 31, 2006), Potential Gas Agency, Colorado School of Mines, November 2007, Table 1, p. 5.

- “Advance Summary, US Crude Oil, Natural Gas and Natural Gas Liquids Reserves,” 2006 Annual Report, Energy Information Administration, Office of Oil and Gas, US Department of Energy, October 2007, Document No. DOE/EIA-0216 (2006).

- “Potential Supply of Natural Gas in the United States,” Report of the Potential Gas Committee (Dec. 31, 2006), Potential Gas Agency, Colorado School of Mines, November 2007, Table 5, p. 8.

- “Annual Energy Outlook 2007 With Projections to 2030,” Energy Information Administration, Office of Integrated Analysis and Forecasting, US Department of Energy, February 2007, Document No. DOE/EIA-0383(2007), February 2007, Table A14, p. 160.

- Linden, H.R., “Reversing the Gas CrisisThe Methane Hydrate Solution,” Public Utilities Fortnightly, Vol. 143, No. 1, January 2005, pp. 34-41.

- Linden, H.R., “Coal No MoreWhat If?” Public Utilities Fortnightly, Vol. 144, No. 9, September 2006, pp. 62-66, Table 6.

- “Annual Energy Outlook 2007 With Projections to 2030,” Energy Information Administration, Office of Integrated Analysts and Forecasting, US Department of Energy, Document No. DOE/EIA-0393 (2007), February 2007, Table A13, p. 159.

- Radler, M., “Oil production, reserves increase slightly in 2006,” OGJ, Vol. 104, No. 47 (Dec. 18, 2006), pp. 20-24.

- Kuuskraa, V.A., Godec, M., and Reeves, S.R., “Unconventional Gas-Conclusions, Outlook sees resource growth during the next decade,” OGJ, Vol. 105, No. 43 (Nov. 19, 2007), pp. 47-53.

- Linden, H.R., “Let’s Focus on Sustainability, Not Kyoto,” The Electricity Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2, March 1999, pp. 56-67.

The author

Henry R. Linden is Max McGraw Professor of Energy and Power Engineering and Management and director of the Energy & Power Center at the Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago. He has been a member of the IIT faculty since 1954 and was IIT’s interim president and CEO in 1989-90, as well as interim chairman and CEO of IIT Research Institute. Linden helped organize the Gas Research Institute (GRI), the US gas industry’s cooperative research and development arm that merged with the Institute of Gas Technology (IGT) in 2000 to form Gas Technology Institute. He served as interim GRI president in 1976-77 and became the organization’s first elected president in 1977. He retired from the GRI presidency in April 1987 but continued to serve the group as an executive advisor and member of the advisory council. From 1947 until GRI went into full operation in 1978, he served IGT in various management capacities, including 4 years as president and trustee. Linden also served on the boards of five major corporations for extended terms in 1974-98. He worked with Mobil Oil Corp. after receiving a BS in chemical engineering from Georgia Institute of Technology in 1944. He received a master’s degree in chemical engineering from the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn (now Polytechnic University) in 1947 and a PhD in chemical engineering from IIT in 1952.

An overview of russia’s gas supply characteristics

- Russia has an unparalleled reserve base (27% or 1,680.0 tcf of world total of 6,182.7 tcf as of Jan. 1, 2007[Reference 9]). E&P revenues are a major component of the economy.

- Russia is the world’s largest gas exporter, and domestic consumption is second highest in the world after the US.

- Gazprom is the major player in the Russian gas industry and is strongly aligned with the Russian government. Gazprom holds Russia’s gas reserves, and produces a total volume almost as large as the entire US market.

- Most of Russia’s supply has historically come from three giant fields in the Nadim-pur-Taz region (Yamburg, Urengoy, Medvez), but these fields are in decline. To replace these fields, Gazprom will be forced to develop more remote fields on the Yamal Peninsula or in the Barents Sea.

- Gazprom’s production target is 20.5-20.8 tcf by 2020 from a level of 19.1 tcf in 2004. Development of these new fields will be highly capital intensive, and it is unclear if Gazprom will be able to attract sufficient capital to fund these projects.

- Gazprom will also try to increase purchase from other Russian companies and from Central Asia.

- Gas exports are exclusively pipeline supplies to the Former Soviet Union and Continental Europe but the first LNG exports will take place when the Sakhalin LNG plant is commissioned, scheduled for 2008. Other planned LNG projects are aimed at the North Atlantic market.

- Leading gas customers include Germany, the Ukraine, Italy, Turkey, Belarus, France, Hungary, Czech Republic, Poland, Austria, Slovakia, Netherlands, and UK. Gazprom controls the export pipeline system and maintains a monopoly on gas exports.

- Gazprom has publicly expressed its disagreement with several aspects of the European Commission’s proposed regulations to promote European Union energy market competition.

Source: Pace Global Energy Services, “Russian Gas Supply to Europe,” p. 4, July 2007, private communication, November 2007