Oil-price patterns—2 (Conclusion): Biggest uncertainty among forces shaping oil price: politics

Manouchehr Takin

Centre for Global Energy Studies

London

With the price of crude oil elevated in the first half of the 2000s by failure of world oil supply to keep pace with growing world oil demand—as was argued in the first article in this series—demand seems poised to grow again (OGJ, Apr. 7, 2014, p. 32).

Expectations for world oil demand have increased following higher consumption in member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development toward the end of 2013. For 2014, world demand could increase by 1.4 million b/d—higher than the 1.3 million b/d increase in 2013. Oil supply outside the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries could increase by 1.6 million b/d in 2014—higher than the 1.4 million b/d increase in 2013. These estimates suggest that the supply-demand balance in 2014 would be more or less similar to that in 2013 and that OPEC would similarly be able to manage the market. Uncertainties remain for both demand and supply, but OPEC is expected to control the market in 2014.1

What's next?

The future price of crude oil depends on the future balance between the flow of world oil supply and demand for oil. The global economy is the most important parameter affecting the oil market, but the economy is itself affected by the price of oil.

The interplay theoretically can be explained as a system with feedback loops and in dynamic equilibrium, persistently perturbed by the changing priorities of politicians, investors, industry professionals, traders, and financial players but, most importantly, by technological breakthroughs and the application of novel techniques. It is impossible to be completely accurate in foreseeing all these possibilities and predicting their future trends. That is why all long-term forecasts provide a number of scenarios based on the level of technology, the status of the economy, government policy, OPEC behavior, and other parameters. Most published long-term oil price forecasts and assumptions cover a range from less than $100/bbl to more than $200/bbl.

No forecast is intended here. However, it is fruitful to follow the analysis of the past 2 decades with a brief discussion of various parameters affecting the future of the oil market.

Future demand

The state of the world economy directly affects the demand for energy and for oil. Any improvement in economic performance will soon be reflected as an increase in demand for oil. Conversely, a recession will soon be reflected as a decrease in demand for oil. Therefore, the important factors for the future of the oil market are how quickly the industrialized countries come out of recession and how fast their economies grow.

Even more critical will be the economic performance of the rest of the world. Future growth of world oil demand will be in these countries. They have large and still growing populations, and most of them are still in their early phases of economic development and will continue to require increasing inputs of energy and oil.

Oil demand of the industrialized countries is not expected to grow that much; for some, oil demand could in fact decline in coming years.

Demand for oil will also be influenced by public policy, such as mandatory speed limits, standards and specifications for the efficient use of energy and oil such as fuel consumption of vehicles, conservation measures, and insulation requirements for buildings. Policy measures also include mandatory substitution of oil by other energies, as well as government subsidies and grants supporting these policies. For example, an increase in the mandatory miles-per-gallon specification for car manufacturers in the US could result in a reduction of about 2 million b/d in future US oil demand in comparison with the case of continuing with former specifications.

Environmental considerations in all countries increasingly direct public policy aimed at reducing the consumption of oil, though most of these policies will have a medium to long-term impact. For example, the more stringent fuel-efficiency specification for vehicles will begin to reduce gasoline and diesel consumption when new, more-efficient vehicles gradually replace less-efficient vehicles now in the fleet. However, some public policies affect demand immediately, such as the imposition of a lower speed limit as was ordered by former President Richard Nixon following the Arab oil embargo in 1973.

The price of oil itself is an important factor in demand for oil, although its effects, direct or indirect and short-term or long-term, vary. Consumers themselves react to price changes. For example, they can respond immediately to a price increase by driving less. They also can respond in the longer term by buying fuel-efficient vehicles.

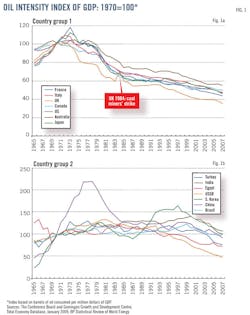

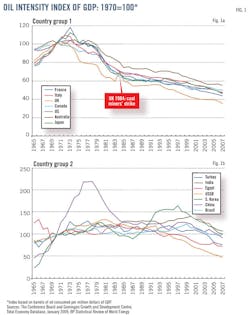

Figs. 1-2 show historical records indicating the potential of these factors of demand. They clearly show that in the last few decades the world has become more efficient in the use of energy, especially oil, and also in the substitution of oil by other energies and that this trend is continuing. These achievements are not usually discussed in the trade press but are clearly shown in historical records as the declining oil intensity of the economy; that is, barrels of oil consumed per million dollars of gross domestic product in real terms.

Oil intensity fell by about 50% for industrialized countries between 1970 and 2007 (Fig. 1a). A similar trend, although less pronounced, is observed for the developing and emerging economies (Fig. 1b). The oil intensity of GDP of these countries remained high during their economic development phase but stabilized and has been declining since the 1990s. The computations shown in these figures applied only through 2007 to avoid distortions of the financial-economic crisis and the oil price collapse in 2008.

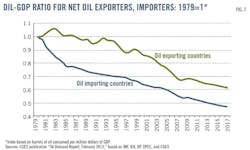

However, other computations by the Centre for Global Energy Studies cover the period beyond 2008. A summary of the results of such computations for two groups of countries, namely net oil-importing and net oil-exporting countries, is shown in Fig. 2 with extrapolation to 2017. As expected, the oil exporters are less oil-efficient, but they have also been reducing their oil intensity, especially since the 1990s, as was shown for a selection of emerging market economies in Fig. 1b.

Future supply

As explained in the first part of this two-part series, many producing countries have strong potential for the growth of their oil production, e.g. Brazil, Iraq, Mexico, Libya, and others. The investments and exploration and development operations in these countries need to be closely followed, project by project, in order to estimate future supplies. In any case, the estimates have to be updated periodically.

Present expectations are that disappointing world oil supply performance over the last decade might not last long. Delayed field-development projects will finally reach completion, and disruptive political situations could improve. The declining production of old fields could be arrested and even reversed by new investment and the application of modern technology. New oil provinces could be found and brought on stream. Supplies of unconventional oil, such as from shale and tight formations, could rise. The surprising success of US oil production could potentially be repeated in the rest of the world.

However, all these encouraging potential supplies will take time to reach their final producing phase. There is strong public opposition to hydraulic fracturing and even to conventional oil and gas operations in many countries. Fracturing is banned in France, and local residents have been protesting against such operations in the UK. No definite forecast can be given under such fluid situations. These conditions, like developments in countries with high potential for conventional production, have to be closely monitored in order to make estimates of future supplies, and the estimates need to be periodically revised and updated.

Oil is a finite resource. The more that is produced, the less is left to discover. Thus, in principle, world oil production cannot go on increasing forever. It will reach a peak and then begin to decline. However, the date of this peak has been hotly debated for almost a century. Each time this topic is examined, new information has become available on the size of the resource base and the state of technology, and a new peak-oil date is estimated—always later.

The advances in exploration and production technology have resulted in the discovery of more resources, and oil production has continued growing, so the goal posts have been shifting. The impressive rebound of US oil production is the latest example.

Examining the market

The presently high oil price is supported by supply constraints. However, an important factor for the oil market will be the role played by OPEC. The organization's policy is to maintain "stability" in the oil market, implying that OPEC will defend an oil price floor. Based on statements by the Saudi and other OPEC authorities and considering the kingdom's budgetary requirements, this price floor is not far below $100/bbl. This could be considered the oil price that OPEC will defend.

However, there is a limit to the extent to which OPEC can defend a price. In a scenario of global recession and collapse of oil demand and increasing global oil supply, the organization will not be able to defend a high price for long. The short-term needs of OPEC member countries could override their long-term priorities and break their production discipline, leading to over-production and a collapse of the price of oil. This has happened before. However, as noted above, the realities of budgetary requirements of OPEC countries themselves and political pressure and lobbying by various government and nongovernment organizations have resulted in OPEC (and some non-OPEC) actions to arrest the collapse of the price of oil and maintain it at a level deemed reasonable.

The greatest uncertainty in the future of the oil market is the influence of politics. Political uncertainty is a problem not only in producing countries, with their reemerging resource nationalism, interference by governments, changing regulations, taxation or export permits, or political turmoil and revolutions; political uncertainty is equally a problem in consuming countries, where governments impose sanctions on oil-producing countries and ban operations of oil companies.

An example is the imposition of limitations by the US and European governments on Libya, Iraq, and Iran dating back to the 1980s and 1990s. In fact, one could argue that the fivefold increase of the price of oil discussed in this series would not have occurred had various sanctions not been imposed and had the international oil industry continued investing and operating in those three countries in the past decades.

Under those conditions, oil supply to the world market would have been 5-10 million b/d higher than it is now, and it is quite likely that the price of oil would have remained in the $20-30/bbl range.

Reference

1. For more details, see Centre for Global Energy Studies, Monthly Oil Report, Vol. 23, No. 1, Jan. 27, 2014.

CORRECTION: The source shown in Fig. 6 of the first part of this series was incorrect. The correct source is CGES.