Double-expansion valve sequence reduces hydrate formation

Khalid Messaoudi

Sonatrach

Illizi, Algeria

Mohamed Khodja

Zahia Bouras

Sonatrach

Boumerdes, Algeria

A pair of valves positioned at the gas lift to produce double expansion addressed the main causes of hydrate formation in production from wells at Alrar-oil Rim field in Algeria, eliminating production interruptions and increasing output.

Clogging of pipelines and other oil and gas infrastructure as a result of gas hydrate deposition requires operators to budget for hydrate prevention, typically through a combination of thermodynamic inhibitors, insulation, and water removal.

Hydrate formation is most prevalent in the gas flow line network, especially offshore, in which transportation of unprocessed well fluids containing water occurs at an ambient temperature of about 4 °C. and a pressure of 50-500 bar. Such conditions can cause hydrate formation severe enough to block the pipe.

Alrar field

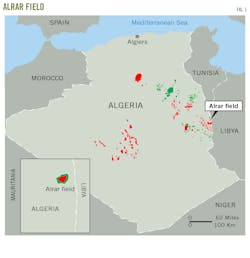

Alrar field is a prolific hydrocarbon province extending across Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya. The field, in Illizi basin, extends eastward from southeastern Algeria to the Libyan border (Fig. 1).

The discovery well in Alrar field was AL#01 well (originally ALA #1), drilled in 1961 in the F-3 reservoir interval. Alrar is divided by a major fault into western and eastern areas. But these areas communicate within the gas cap along the fault, with the pressure history of the western area showing no production from 1965 to 1995. Subsequent drilling has defined about 500 sq km of the eastern area and about 250 square kilometers of the western area as productive.

F-3 reservoir interval is sandstone, with hydrocarbons found in stratigraphic traps on a northward-dipping monocline. Alrar field has very large gas caps, a relatively thin oil rim, and downdip aquifer intervals.

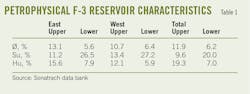

Development of Alrar-oil Rim started in 1969 with the drilling of five wells: NAL1#3, 1#6, 107, 1#0, and 1#1. NAL1#3 was the first well drilled in F-3’s Devonian reservoir on the northern part of Alrar field, and the gas-oil contact was found at 1,948 m. NAL106 was the second well drilled in the reservoir, with water-oil contact at 1,958 m. Table 1 outlines petrophysical reservoir characteristics.

The lower 30-40% of F-3 reservoir part is clayey and more compact than the upper part. The reservoir’s sandstone is divided accordingly: upper and lower.

Alrar-oil Rim has more than 35 producing oil wells, including 19 using gas lift.

Gas lift project

Development of Alrar-oil Rim included drilling 19 wells in the eastern sector and conversion of seven existing injector wells into production wells. Production from Alrar-oil Rim started mid-January 2006 with two wells, AL#5 and #7 (Manifold M6H), and an approximate flow rate of 436 cu m/day. Seven other wells AL5#8, 5#1, 5#4, 6#1, 6#2, 6#3, and 6#5 were connected to STAH’s oil treatment center at the end of 2006.

Problems at the field included reservoir pressure dropping and an increased water-oil ratio. In 2010 Sonatrach’s production engineering division (PED) performed a gas-lift engineering study. Due to the unavailability of equipment and the conditions required by PED, however, the gas lift project was postponed.1

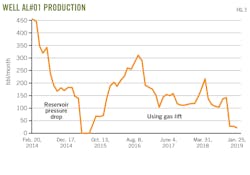

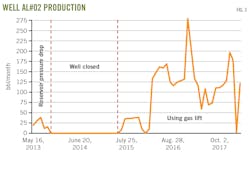

End-2013 through the beginning of 2014 marked the connection of many wells to the gas lift network. Fig. 2 shows well AL#01’s production profile before and after using gas lift. Fig. 3 shows AL#02’s post-connection production profile using gas lift.

Hydrate formation

Equations 1-3 calculate temperature fluctuations at the surface of the soil. Temperatures at a given depth are calculated using Equations 4-6.2

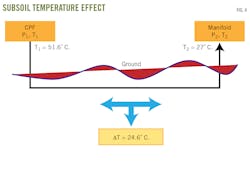

Alrar-oil Rim field subsoil temperature variations affected the gas-lift network (Fig. 4). Follow-up research defined the impact of radiant energy changes during the day and night.

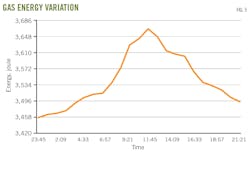

From the central processing facility (CPF) to the manifold a 24.6° C. difference of temperature meant the subsoil had absorbed energy. Fig. 5 shows the resultant variation of gas energy over 24 hr.

The Joule-Thomson effect impacted the Alrar-oil Rim gas lift network. The flow rate of the gas lift was affected by Joule-Thomson and hydrate formed at the flow control valve restriction. Hydrate deposition decreases the gas flow rate, eventually stopping production.

Case study

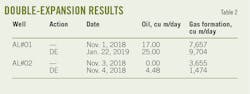

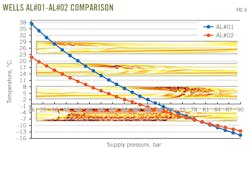

Evaluation focused on Wells AL#01 and AL#02, the most affected examples in the field. Figs. 3 and 4 present AL#01 and AL#02 production profiles and the impact of hydrate formation, visible as non-productive time (NPT) recorded each winter. Three years were selected for this study. Equation 7 calculates the degree of production restriction.

A noninsulated pipe used to transport the gas undergoes a polytropic transformation as a result of the partial heat exchange between the pipe and its environment. Equation 8 defines the polytropic state between the isothermal case and the adiabatic case. Equation 9 represents the variation of the temperature according to pressure, providing the range of the pressure favoring the appearance of hydrates.

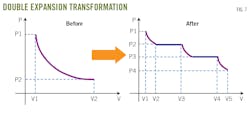

Adjustment involved installation of valves at a defined distance from each other to decrease supply pressure gradually until it reached recommended injection pressure (Fig. 7). Table 2 shows the results.

References

- Sonatrach data bank.

- Guellouz, M.S. and Arfaoui, G., “Potential of surface geothermal energy for the heating and air conditioning in Tunisia,” Review of Renewable Energies CICME’08, Sousse, Tunisia, Apr. 11-13, 2008.

- Naseer, M. and Brandstatter, W., “Hydrate formation in natural gas pipelines,” Transactions on Engineering Sciences, WITpress, Vol. 70, 2011.

- Jassim, E.I., “Modeling of Hydrate Deposition in Loading and Offloading Flowlines of Marine CNG Systems,” International Journal of Sustainable and Green Energy. Special Issue: Renewable Energy and Its Environmental Impacts, Vol. 3, pp. 1-6, 2014.

- Michail, V. and Gaganis, V., “Assessment of Hydrate Formation Parameters in Production Wells,” Master Thesis in Production Engineering, Technical University of Crete, September 2015.

- Straume, E.O., “Study Of Gas Hydrate Formation And Wall Deposition Under Multiphase Flow Conditions,” PhD Thesis – Postgraduate Program in Mechanical and Materials Engineering, Federal University of Technology – Paraná, Curitiba, p. 232, 2017.

- Guo, B.Y., Lyons, W.C., and Ghalambor, A. “Petroleum Production Engineering,” Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2008.

The authors

Khalid Messaoudi ([email protected]) is a senior petroleum engineer at STAH Production Division, Sonatrach, Illizi, Algeria. He began his carrier as a CNC programmer at SOREMEP-Survey Co. Metal and Plastic Realization, moving from there to a management position in material resources at STAAR- Engineering Civil Work Co. He next worked as an operations engineer at Sonelgaz before joining Sonatrach as a Level 2 petroleum engineer. He obtained his engineering degree (2006) through the University of Abou-Bakr Belkaid Tlemcen, where her also earned his post-graduate diploma of in material science (2012), and his PhD in mechanical engineering (2018).

Mohamed Khodja ([email protected]) is a director at the central directorate of research and development, Sonatrach, Bourmerdes, Algernia. He started his carrier as an engineer at the directorate of reservoir research of Sonatrach. He obtained his master’s degree of geosciences-risk and environment (2006) through the University of Louis Pasteur, Strasbourg, France, then his PhD in chemical engineering and environment (2008) through the National Polytechnic Institute, Toulouse, ENSIACET-Paul Sabatier University, and CRMD-Orleans University, all in France.

Zahia Bouras ([email protected]) is an English teacher in both the general and technical fields at the Algerian Petroleum Institute (IAP)-Sonatrach. She obtained her English degree (2004) through the University of Blida, Algeria, and a financial accounting diploma in 2006. She was responsible for IAP’s English-language ‘Drilling and Petroleum Options’ in 2010.