Developing the field

Great White, Silvertip and Tobago – the Perdido development’s three fields – contain many producing zones, large volumes of hydrocarbons in-place, and a considerable amount of uncertainty.

Much of the oil and gas from Perdido will come from the Paleogene geological system, which includes the M. Oligocene Frio Sds., L. Eocene WM12 Sd., and the L. Paleocene WM50 Sds. Together, these three reservoir zones are known as the “Lower Tertiary,” reservoir intervals in the Gulf of Mexico that no other operating company in the gulf has tapped before. Some industry analysts are calling the Eocene the most significant oil trend since the discovery of Prudhoe Bay.

A major part of the current plan is to drill as many of the wells as possible from the host platform, rather than from mobile deepwater vessels that complete the wells, then leave the drilling location. That offers two main advantages. First, drilling from your own platform is less expensive than hiring a deepwater rig. Second, having access to the wells from the host platform allows petroleum engineers to learn more about the producing zones and to make adjustments as needed. The downside of drilling most of the wells from a central location is that the wells are often highly deviated, which increases their cost.

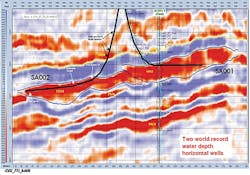

Perdido’s first satellite wells, of course, were drilled from mobile offshore drilling units (MODUs), which allowed development of the field to start while the spar was being built. In December 2008, the Noble Clyde Boudreaux set a world record by completing a production well in 9,356 feet (2,852 meters) of water. The Boudreaux also pre-drilled 22 wells to about 2,500 feet below the mud line at the spar location. Two of these wells have been deepened to the WM12 Sd. The remaining 20 wells will be deepened later to their reservoir targets and then completed. The MODU was released from the field in November 2009 after completing some 2.2 million man hours without a lost-time incident. Development drilling is continuing now from the spar and from Noble’s newest ultra-deepwater rig, the Danny Adkins.

A challenging environment

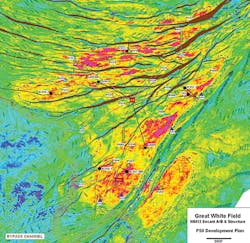

Great White, the largest of Perdido’s three fields, is one of a series of very large, heavily-faulted anticlines known as the Perdido Fold Belt, which is a very different geological environment than most of the Gulf of Mexico. A deep submarine canyon cuts across the field, and one escarpment near the spar is nearly 1,500 feet (457 meters) high. The reservoirs are also far from other areas of oil and gas production in the gulf.

“That is challenging for many reasons,” Eikrem says. “The rugged sea floor makes it harder to install subsea equipment and pipelines, and the extreme water depth makes drilling more difficult. We also have a wide range of permeability in our reservoirs, the reservoir pressure is low, and there are significant differences in the quality of the oil.”

On the heavy side, the API gravity in the M. Frio at Silvertip Field is as low as 16 degrees. The lightest oil runs about 38 degrees in the Great White Field’s WM50A Sd.

“But even with Perdido’s challenges,” Eikrem says, “there is real growth potential out here because of the size of our asset. The volume in place is phenomenal. If we can access it economically, this project will go on for many years.”

Early drilling program

Great White was discovered in 2002, and all of Perdido’s exploration and appraisal wells were completed by the end of 2004.

By the end of 2009 the project had eleven exploration and appraisal wells including two sidetracks. In addition, eight development wells had been drilled and six had been completed. The current plan calls for as many as 35 wells, with about two-thirds of them drilled from the spar. The most distant satellite well so far is on the seabed about eight miles from the host. Development drilling is scheduled to continue beyond 2016.

Rigging up the spar

“When I first started on this project in January 2003, it was wide open,” Shumilak says. “We were still trying to figure out what the reservoirs were like, and how in the world we were going to develop something in 8,000 feet of water.”

Shumilak’s group moved from supporting the Subsurface team to designing the wells, then turned its attention to the spar’s drilling rig. Weight was always an issue. Putting wellheads and much of the separation equipment on the seabed made the spar itself smaller and lighter, but the drilling rig was going to add a lot of weight that had to be supported by the buoyancy of the spar.

“Once we decided we were going to put a spar out there, our team began working on specifications for the rig and our interface with the spar,” Shumilak says. “We needed a rig powerful enough to drill long, complicated wells, and a spar that could support it. There was a lot of give-and-take, trying to marry the rig to the spar. We worked extensively with the spar and mooring team and with the topsides team.”

Building a new rig for the spar would be expensive, and as it turned out, unnecessary. Until 2007, the Helmerich & Payne (H&P) 205 had been on Shell’s Ram Powell deepwater platform in the Gulf of Mexico. The rig had a good working history and safety performance, and it was no longer needed on Ram Powell.

“We demobilized the H&P 205 rig from Ram Powell and took it to the Kiewit Offshore Services yard in Corpus Christi in February of 2007,” Shumilak says. “There we made some upgrades, because the rig had been working on a TLP. The motions and stresses are different on a spar, so we needed to modify the rig.”

A tension-leg platform, for example, has very little pitch and roll, but it will drift on its mooring lines in a slow figure-eight. Spars don’t drift as much, but they will pitch more than a TLP. To compensate, the H&P 205 rig’s skid beams and skid base were modified. There were also structural upgrades to the rig floor and derrick.

“The H&P 205 was in the Kiewit yard at the same time they were building our topsides,” Shumilak says. “That was convenient, because we could easily go from one to the other. There was a lot of interface management.”

The work on the rig was completed in December 2008, but it was not taken offshore until July 2009. The H&P 205 installation was completed the following month and the rig was immediately put to work installing Perdido’s first two subsea separator caissons. Most of the experienced crew that had operated the H&P 205 on Ram Powell stayed with the rig and are now on the Perdido spar.

“A number of H&P’s rotating crews also work exclusively for Shell, and that enhances our safety program,” Shumilak adds. “Even though they move from one facility to another, they know our safety culture. They know the way we work and operate, and they know our foremen and superintendents.”

As the rig neared completion in the Kiewit yard, for example, new crew members were brought in to work with the experienced hands. As one of the foremen said, “We’re building the safety culture here that we’re going to take offshore with us.”

One popular safety program is called, I stopped a drop! On a drilling rig that is 15 stories tall, dropped objects are a serious hazard. A forgotten tool in the derrick or any small item that vibrates loose can be deadly. As one rig hand explained, “A one-pound bolt falling from 100 feet up makes quite a dent.”

Workers who point out such hazards are rewarded, and they have the satisfaction of knowing that they may have kept someone else from getting hurt.

Safety offshore

Working offshore is inherently dangerous. The work is non-stop. People are moving equipment that weighs tons, yet the offshore safety record for the Perdido development has been outstanding.

“I give a lot of credit to the onsite leadership,” Shumilak says. “Day in and day out, the Shell foremen and all the site leads stressed safety. They focused on it in their pre-tour meetings in the morning and in all of their pre-job planning. They talked about safety again at the end of their shift. Safety has been a continual theme offshore, and it really pays off.”

Because of the extreme water depth, remotely-operated vehicles (ROVs) like this one were used to complete much of the subsea work.

The way contractors managed their experienced people is a good example. Anyone who was new to a particular job – regardless of his or her time in the field – was called a “short service” employee. The number of short service employees was kept to a minimum, but when anyone did fall into that category, mentors were always nearby.

An integrated team

From the beginning of the project through the end of 2009, Perdido’s contractors and Shell employees logged more than 10 million man hours without a lost-time injury. That is just one measure of Perdido’s success. Shumilak credits a strong integrated team and good management.

“One thing I’m most proud of is the integrated team we had throughout this project, and the freedom that management gave us to explore new ideas, ” he says. “We began with a whole range of possibilities and solutions, so we gathered an experienced team of civil engineers, rig folks, subsea engineers and production specialists. The interface and communication was outstanding. Without that, we couldn’t have pulled this off.”

From the beginning, the team had few constraints. If a project as bold as Perdido was going to be successful, creativity and flexibility were the keys.

“The solution we have right now didn’t even come up until three months before we went to decision gate three, which is System Selection,” Shumilak says. “We had decided to build a spar with DVA dry trees, but artificial lift and flow assurance were still problem areas. That’s when G.T. Ju, our Subsea lead, suggested that we combine the two into a wet-tree DVA system instead.”

The design team thought it over. Management gave them two months to evaluate the idea and make a proposal.

“We rounded up all the project leads, explained the idea and started working,” Shumilak recalls. “We came back, pitched our case, and management bought in. The ability to do that was fantastic. Without it, I’m sure that our final solution would not have been as good.”