Brazil's energy crisis complicates progress in gas, power markets, but outlook brightening

Brazil is in the middle of a dramatic electricity crisis. The electricity shortage is leading the government to imple- ment a rationing program under which three fourths of the 170 million Brazilians have been told to immediately cut consumption by 20% or face blackouts and power interruptions.

The government claims that the measures are needed because Brazil is facing its worst drought in decades. This has affected the country's power generation capacity, which is 95% dependent on hydroelectric plants.

However, at least two other important factors can be pointed out as causes for the current energy crisis: 1) the country's negligence in perceiving that energy demand growth had been consistently outstripping the increments in generation capacity growth during the last decade and 2) the lack of corre- sponding policy initiatives to provide incentives for new power capacity, particularly thermal plants.

Brazil's economy, the world's eighth largest, grew a robust 4.4% last year, and initial forecasts were for a similar performance this year. However, 6 months of obligatory electricity ration- ing will certainly make that target unrealistic. With approaching general elections scheduled for yearend 2002, fears of recession, inflation, and the loss of foreign investment are rising. The government is taking countermeasures, including the opening of electricity opportunities to private companies and the announcement of direct state investment in power generation and electricity transmission. While some new capacity may be confidently projected, increases in power gen- eration must both meet expected growth in demand and make up for the lack of investment in recent years.

For the newborn Brazilian natural gas industry, the outlook for the next few years is interesting. Despite the delays in long-awaited regulations regarding prices and tariffs, many gas and power projects are finally coming through. Opportunities in gas transpor- tation and distribution, as well as challenging ventures in gas-to-power will certainly emerge in all parts of the large Brazilian territory.

Brazil's energy requirements

Brazil is a stable democracy with a population of about 170 million inhabitants, a territory of 8.55 million sq km, and a gross domestic product of $600 billion (2001 estimate). It has the world's fifth largest territorial area, sixth largest population, and eighth strongest economy, accounting for about 40% of Latin America's wealth. The country has solid political institutions and no significant restrictions on foreign investments. The economy has remained consistently stable since 1994, when annual inflation dropped from two-digit monthly figures to civilized annual rates lower than 3%.

The dynamism and diversity of Brazil's economy, coupled with the sizeable consuming market it represents, has quickly attracted investors of all types and origins during the last decade. Major changes in the constitution and the establishment of new regulatory frameworks for critical sectors such as oil and gas, electricity, telecommunications, transportation, water, and sewage, among others, were crucial factors for Brazil's economic transformation. On the other hand, Brazilian enterprises that have quickly learned the new reality of worldwide competition became stronger and gained new markets, using their important local knowledge within the country or stepping into other territories with competence and creativity.

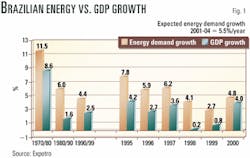

But not everything has prospered, however. Although it is clear that Brazil's opening has been positive for the country, some ramifications were not seriously considered. The main problem seems to be the immediate increase in energy demand caused not only by the intensity of the national economy but also by the rising living standards of the population. Despite registering energy demand growth rates consistently above GDP growth for various years (Fig. 1), Brazil seemed not to notice that, irrespective of annual rainfall, it would need to source new ener- gy to satisfy increasing expectations by a population that had repressed its energy needs for years.

Brazil's energy balance clearly characterizes the country as being much like a thirsty nomad that reaches an oasis of economic stability after having erratically marched through a desert of hyperinflation and recession. The wanderer quenches his thirst but is now used to normal water intake. Brazil has equally depleted its energy reserves to satisfy its unleashed, formerly repressed demand, after economic stabilization. But the new comfort level of its citizens and companies has also brought the country to new levels of energy use that will have to be sustained and increased throughout the years to come.

Current energy mix, targets

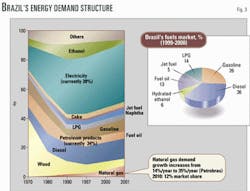

Brazil's energy requirements and sources are summarized in Fig. 2 for static 1998 and 2005 numbers. Fig. 3 shows a picture of the country's energy demand structure from 1970 to 2002.

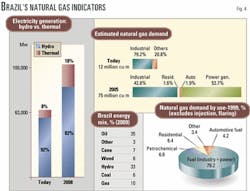

The ramp-up of the participation of natural gas in the country's energy mix is a consistent projection from governmental and private sources in Brazil. A negligible energy commodity as recently as 10 years ago in Brazil, natural gas has suddenly become the most important alternative to hydroelectricity in Brazil's energy policy plans. Today, hydropower plants still generate 92% of the country's energy. In Fig. 4, a comparison with thermal plants in the forecasts for 2008 leads to a market share of 18% for thermal plants vs. 82% for hydro (this comparison excludes nuclear energy). As a result, the share of natural gas in the overall energy mix is expected to reach 10% in or before 2008.

Brazil's new generation capacity to be installed throughout 2001-02 is expected to be of three types: gas-fired thermal plants (9,073.4 Mw), new hydro plants (6,381.20 Mw) and the so-called "small hydropower units" (PCHs, or "pequenas centrais hidrelétricas") that will account for an additional 400 Mw in generation capacity. The list of the main projects announced as of this writing is provided by Figs. 5, 6, and 7.

Trends in the average annual increase in new generating capacity in Brazil is reflected by Fig. 8, showing the discrepancy between what was done in the "dormant" recent years and what is projected now that the country has awakened to the energy problem. The same graph also shows the evolution of energy supplies during these periods.

Brazil's gas systems, opportunities

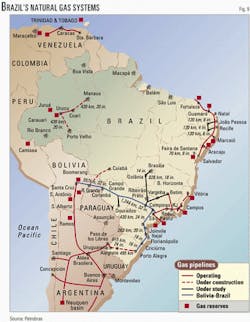

Brazil has three distinct natural gas systems, each comprising supply sources, transportation and distribution lines, and consuming markets (Fig. 9).

The South-Southeast system is by far the most important, in terms of magnitude (Fig. 10). The system has the Bolivia-Brazil pipeline (Gasbol) as its backbone, and the region is formed by the southern, southeastern, and central-western states of Brazil. Today, the system encompasses the gas reserves of Bolivia and northern Argentina to the west, and the offshore producing basins of Santos, Campos, and Espírito Santo off the Brazilian Atlantic coast to the east. The main gas carrier is the Gasbol pipeline (operated by TBG) coupled with some existing pipelines linking Campos basin gas with the São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro markets. The markets currently supplied range from Corumbá and Campo Grande, located at the entrance of Bolivian gas into Brazil, through all the main industrial centers of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro states and the coastal regions of Paraná, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul states.

This immense area is rapidly developing based on energy-intensive industries. The region represents 82% of Brazil's industrial output and 66% of the country's GDP. Its 90 million inhabitants consume 75% of the nation's energy production. In light of the current energy crisis, several thermal pow- er generation projects have popped up throughout the region. Many of them will constitute important anchors for the consolidation of natural gas as a regional energy source.

The plans for the expansion of the existing system include the links to additional supply sources in Argentina, other alternative routing for Argentine and Bolivian gas (through the looping of Gasbol and the construction of lines linking Rio Grande do Sul state to the northern Argentina states and crossing Uruguay to linking Porto Alegre to Buenos Aires. The discovery and development of new gas reserves off the Brazilian coast is widely expected, given the amount of exploratory efforts that will result from the sale of blocks in three recent international bidding rounds. Petroleo Brasileiro SA has been carrying out exploration for 2 decades in the region and has recently been allowed to also join forces with strong private partners through directly negotiated joint ventures. Other projects in the Southeast region involve branches of the main Gasbol trunk line to the city of Cubatao (130 km), in the state of São Paulo, and another from Cam- pinas to Rio de Janeiro, to complement the current supply coming from the Campos basin to six thermal plants there. This will be the second line between São Paulo and Rio. A pipeline already exists between these cities, named Gaspal, but the expansion of its current capacity was ruled out due to regulatory constraints. The new São Paulo-Rio project is programmed to have a 10 million cu m/day of capacity.

As to new markets, expansions are expected to occur towards main centers such as the capital city Brasília, Belo Horizonte (third most populous city of the country, capital of Minas Gerais state), and Goiânia and Cuiabá (capitals of Goiás and Mato Grosso states, respectively). Industrial complexes such as Vitória (Espírito Santo state) and the Londrina-Maringá axis (in Paraná state) will also welcome the access to natural gas for their energy-intensive activities.

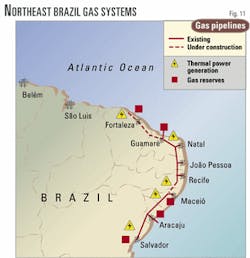

In the Northeast system, the main regional carrier is Nordestão Pipeline (operated by Transpetro, a wholly owned subsidiary of Petrobras). Nordestão is composed of segments including Guamaré-Cabo, Guamaré Fortaleza, Pilar-Cabo, Pilar-Atalaia, and Atalaia-Aratu. These total almost 1,600 km of pipelines that integrate the whole region throughout the coast, where the greatest portion of potential natural gas consumption is located. There is also a good possibility for the discovery and development of new offshore reserves. The Equatorial Margin basins (namely, Potiguar-Ceará, Barreirinhas, and Pará-Maranhão) were some of the attractions of the third and latest bid round organized by the National Petroleum Agency (ANP). These basins had already attracted the attention of the majors in 2000, when great consortiums were formed to operate blocks off the Amazon River mouth (Foz do Amazonas basin). On the Atlantic margin, formerly underexplored basins such as Camamu-Almada, Cumuruxatiba, and Pernambuco-Paraíba will probably be additional targets for existing operators in the active Recâncavo and Sergipe-Alagoas basins. The viability of imported sources of gas, expected to result from LNG projects planned for both Suape (Pernambuco state) and Pecém (Ceará state) will greatly depend on regional pricing practices, the competition with local reserves, and especially the attractiveness of the North American markets for LNG.

On the marketing side, electricity generation will certainly have to set the stage in providing demand scaled to pull the development of the industrial, commercial, and residential gas consumption markets in the future.

Surprisingly enough, automotive gas is gaining growing confidence and preference among drivers in the coastal capitals of the Northeast.

Local distribution companies will have a crucial role in mitigating the risks for the gas production chain, and their margins will also have to enable significant investments in distribution pipelines to bring gas to the interior.

The Amazonian system maintains its usual slow pace, and the level of political animosities between the govern- ment of Amazonas state and Petrobras has risen lately due to the state's launch of an international tender calling for equity participation in Amazonas state's local distribution company, Cigás, for the transportation of natural gas from the port of Coari to Manaus. The state's bid did not specify any type of transportation mode, but all the speeches at the launching ceremony were clearly favorable to any type of river barging system rather than pipelines. Although the official arguments ranged from environmental concerns to the flexibility of deliveries along the river, the true reason for this preference may lie in a regulatory reason: If a pipeline is built, the regulations regarding its construction and the transportation activities will be federal (mainly ANP's), while barging the gas downriver could be considered as part of the local distribution system, remaining in the hands or under the jurisdiction of the state.

Gas prices, E&P, transportation

Demand for gas in Brazil is expected to grow from 3% of the energy mix to an estimated 10% by 2005, a great portion of this to feed an average 5,000 Mw/year of increases in thermal power capacity.

Petrobras expects to be marketing 70 million cu m/day of gas by 2005 (Fig. 13), of which 64% will come from the company's own production. This growth in gas sales is expected to be split 51% thermal power, 41% industrial, and 8% other uses.

In August 2001, the federal government announced the long-awaited regulations for the pricing of natural gas to be sold to thermal plants under the so-caled "Emergency Thermal Program." Gas producers will be expected to carry intrayear foreign exchange risk. A tracking account mechanism will be used to capture the related cost, which will be included in annual gas price readjustments. Considered as a reasonable interim solution, given the total lack of better alternatives within the Brazilian gas industry scenario, the allocation of economic risk within the limited portfolio of gas producers, with tracking account mechanisms subject to the regulator's mood, might function well in a preliminary phase.

However, as the immaturity of the gas market in Brazil passes and Petrobras's dominance in the gas production and transportation sectors diminishes, a more market-oriented resolution will be required to guarantee continuous E&P investment.

E&P investment in Brazil is expected to focus heavily on oil rather than gas exploration, given the historic predominance of associated gas. Nevertheless, some regions of Brazil have gas-prone areas of interest, and very soon some new gas-producing provinces will start to compete with imported gas, as both reserves and consumption keep a constant growth path. Well-organized, isolated systems could attract new E&P investment to regions such as the Amazon and the Northeast.

Meanwhile, LDCs are expected to play an important role, in terms of the development of new markets and uses and as a major risk mitigator along the chain. Within 5-10 years, the tendency will be for transactions in the wholesale market to gradually move from wellheads and consumer sites to hubs at major interconnections of interstate or intrastate pipelines.

In the Bolivia-Brazil gas trade, some significant changes, especially in pricing, might still occur. Over the last few years, the wellhead price for Bolivian gas rose from $0.75/Mcf to about $1.80/Mcf under a contract that ties the price to a basket of fuels. This volatility has been a factor that in- creased the reluctance of investors in gas projects to make long-term financial commitments. A more stable gas price would seem to benefit both buyers and sellers, given the abundant supply in Bolivia and only one significant market. We would expect the new contracts to have a floor and a ceiling for gas prices, leaving a range of $1.10-1.40/Mcf for variations.

This is a sensitive issue for Bolivia, because gas sold through the existing Gasbol pipeline could represent about 8% of that country's GDP; a less volatile formula would enable the country to maintain its position as Brazil's main supplier for the long term. Bolivia's gas reserves of about 38.8 tcf (proven plus probably, according to recent government estimates) compare favorably with Argentina's 26.4 tcf (proven) and Brazil's current 7.6 tcf (proven). The projections of imported gas supplies compared with domestic sources is given in Fig. 13. Capacity of the first Bolivia-Brazil pipeline is currently 17 million cu m/day and is expected to grow to a maximum of 30 million cu m/day by 2003. A second pipeline is now being strongly considered.

The regulations on transportation activities, despite having to deal with the special hegemony of Petrobras, cannot afford to be unfavorable to new investment in infrastructure, a clear bottleneck in the Brazilian chain. The recently implemented open-access regime has to guarantee the flexibility of the sources of supply for natural gas to compete for markets. It will be important that Brazil honors its tradition of respecting and enforcing contracts in order to have take-or-pay or ship-or-pay clauses effective, for instance. This will assure future investments. Some regulatory uncertainties regarding the limits of the jurisdiction between federal and state governments (special cases in the Amazon and the Northeast) will dominate the scene in the next 2 years. However, it is expected that the lack of a business culture of gas (and liquids) transportation will be overcome with entrance of new players.

Electricity in Brazil

Since 1964, when the state-owned holding company Eletrobrás was created to control the power sector, Brazil's power expansion model was fed by external financing, government re- sources, and public tariffs. In the early 1980s, the Brazilian debt crisis virtually brought international lending to an end. Then, the internal fiscal turmoil virtually exhausted the public sector's ability to make investments in the energy sectors. To worsen matters even more, the hyperinflation years corroded the actual value of the power tariffs, further damaging investment capacity.

During the 1990s, the government decided to completely remodel Brazil's power sector. First, in 1993, an attempt to renegotiate debts among energy companies was conducted. In 1995, constitu- tional amendments were enacted, introducing the possibility of direct private investment in the power market in Brazil. In 1996, a new regulatory board was created: ANEEL, the National Electricity Agency (Agância Nacional de Energia Elétrica). Two years later, a federal law defined the new legal framework for the sector.

In parallel to this, a privatization process started with the sale of Escelsa, a local distribution utility, in the state of Espírito Santo in 1995. The government decided to trigger the subsequent privatization of local distribution companies in the states, aiming to reduce the possibility of default in the sector. The federal government even offered incentives to the states, by anticipating the revenues to be obtained from privatization. As a result of the sale of state distribution companies, some 65% of all electricity distribution is currently in private hands. Major multinationals have entered the market, such as France's Electricite de France, Spain's Endesa SA and Iberdrola SA, and US-based AES Corp., Enron Corp., and Reliant Energy. Losses in the power distribution sector diminished by 9% during 1995-99, while productivity jumped 136% as distributing companies, as a group, moved from a -3% return on assets in 1993 to a 4.3% return in 1999.

The same successful experience was not to be reproduced with electric power generation companies, precisely the sector where increases in capacity were urgently needed. Only four generation companies were sold from September 1996 to October 1999: Cachoeira Dourada in the state of Goiás, Gerasul in the state of Santa Catarina, and Paranapanema and Tietâ in the state of São Paulo. And there have been no strong incentives for the new owners to increase their output.

Clearly, the federal government lost momentum, as the political opposition to privatization in the sector mounted. Putting Furnas, which supplies mostly the states of Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro, up for sale caused strong animosity between President Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Minas Gerais Gov. Itamar Franco.

Franco refused to accept the privatization of Furnas and started a fight with AES, the largest private shareholder in the electrical utility, Cemig, in his home state. Similar political and corporate entanglements were expected in connection with the sale of Chesf, the company that generates energy for the entire Brazilian Northeast.

Without good reason to proceed-considering this process was not ex- pected to increase the government's popularity in the first place-and in the absence of a strong leader, as was the case with telecommunications privatization, the reform of the electricity sector came to a halt, and private investments have been canceled or delayed.

As to gas-fired power plants, the lack of proper regulation added un- certainty for po- tential investors. A positive aspect was guaranteed gas supplies from Bolivia and Argen- tina, and the government helped the construction of the Bolivia-Brazil natural gas pipe- line through Petrobras. However, the use of natural gas to generate electricity was not immediately adopted, as it was not clear to the investors how they would pay for the gas supplies in US dollars while collecting energy prices from Brazilian consumers in local currency, plus taxes.

Regulators have also failed to encourage investment in electricity transmission lines. Thus, the effects of the dry season in the states of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Minas Gerais could have been offset by importing energy generated elsewhere in the country. As things stand currently, all transmission lines are at full capacity.

Energy crisis implications for gas

One of the major drivers for growth in gas demand in the 2001-5 period is expected to be the thermal generation plants. This growth has been heavily delayed in recent years, primarily due to the lack of regulatory resolutions (including gas prices), which has prevented the financing of independent power producers.

Recent gas price resolutions removed major impediments to the Priority Thermal Plant Program: a maximum price equivalent to $2.581/MMbtu, with annual readjustments and overall maximum volume limited to 40 million cu m/day. Due to the harsh reper- cussions of the energy crisis, there has been a mobilization of a high-level government team to resolve the so-called "structural issues" (i.e., tariffs, contracts, financing parameters, environmental licenses, taxation, old versus new energy competition). Firm willingness and support (direct or indirectly through Petrobras, the national development bank BNDES, or Eletrobras) has been given by the federal government to install an additional 2,200 Mw of new thermal power generation capacity by yearend and then continue with yearly additions of at least 5,000 Mw until 2005. Direct investments in important interregional transmission lines have been announced.

As a result of the energy crisis, economic growth prospects have affected confidence in the country's potential. Gloomy feelings about job security coupled with a direct, traumatic impact in the comfort of everyday life has raised uncertainties over the govern- ment's capacity to manage the electricity sector. This is reflected directly in the voters' views. Recent polls by the main weekly national magazine, Veja, detected some impressive figures: 55% of the voters blamed the government for the energy crisis, 20% blamed the lack of rain, 15% the lack of conservation policies, and only 6% pointed out privatization as the main reason. Yet, 77% still declared to be proud of being a Brazilian, while 91% of the voters declared to be willing to follow the necessary rationing measures.

On the economic front, growth prospects will be affected, mainly by the direct impact of energy rationing on industries. GDP forecasts have been reduced from 3.5-5.0% to 2.5-3.5% in 2001 and from 4-6% to 2.2-3.5% in 2002. On the political front, the energy crisis significantly damaged President Cardoso's popularity and consumers' general level of confidence in the economy, increasing uncertainty regarding the 2002 presidential election. Government's ability to manage the succession will now greatly de- pend on economic growth, as the support from the coalition parties could weaken as result of recent political crises. Although energy rationing will inevitably slow the economy, the government is starting to receive positive signs from its campaign on rationing results and the new generation capacity increments. Oppo- sition parties and isolated candidates are expected to use the energy crisis as leverage for their political platforms. However, none of them have gained the full confidence of citizens yet, as their energy policy plans remain too theoretical and superficial. Just proposing the halting of the privatization processes or the massive direct investment by the state just does not seem sufficient anymore to convince the new, demanding Brazilian voter, avidly thirsty for the energy comfort his country is certainly able to provide.

Bibliography

ANP (Agância Nacional do Petróleo), "Indústria Brasileira de Gás Natural: Regulação Atual e Desafios Futuros, Series ANP, No. II, Rio de Janeiro, 2001.

Ferreira, Alcides, "Brazil Energy Woes: California (Bad) Dreamin'," InfoBrazil.com, São Paulo, Apr. 6, 2001.

Folha de S. Paulo (André Soliani), "Petrobras joga for a US$1 milhão por dia," São Paulo, Jun 10, 2001.

Linhares Pires, José Claudio, "Desafios da Reestruturação do Setor Elétrico Brasileiro," Discussion Paper, BNDES, Rio de Janeiro, March 2000.

Merrill Lynch (Frank McGann, Marcus Siqueira), Latin America Oil and Gas Update, New York City, June 5, 2001.

New York Times (Larry Rohter), "Brazil, Fearful of Blackouts, Orders 20% Cut in Electricity," New York City, May 19, 2001; "Energy Crisis in Brazil Brings Dimmer Lights and Altered Lives," New York City, June 6, 2001.

Prates, Jean-Paul, "Regulatory and Economic Aspects of Brazilian Gas Markets," speech and presentation at Latin Gas 2001, Sheraton Towers, Rio de Janeiro, May 2, 2001.

Prates, Jean-Paul, "Brazil's Gas Supplies: Repercussions of the Energy Crisis," speech and presentation at the Brazil Energy Roundtable of the Institute of the Americas' Gas and Power Markets Convergence, Rio de Janeiro, June 25, 2001.

The author

Jean-Paul Terra Prates holds an LLB from the Law School of the University of Rio de Janeiro, a Masters degree in economics and management (Mastère Specialisé en Economie et Gestion) from the Institut Française du Petrole, Paris, and an MS in energy management and environmental policy from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He has experience in international petroleum agreements, working at Petrobras Internacional SA during the 1980s, and for the last 10 years has been working as a strategic consultant and energy attorney for petroleum and energy companies entering the Brazilian market. Prates remains involved in the developments of the opening of Brazilian petroleum sector, especially regarding its regulatory and institutional aspects. He acted as a legal advisor for the Ministry of Mines and Energy and the National Petroleum Agency at the first phase of the new regulatory process. Prates is a founding partner and executive director of the multidisciplinary energy consulting group Expetro, headquartered in Rio de Janeiro, and a member of the law firm Prates & Carneiro Advogados, the first Brazilian law firm to specialize in energy counseling.