E. Mediterranean gas work faces geopolitical hurdles

Full development of giant natural gas discoveries in the eastern Mediterranean Sea depends on solutions to tough geopolitical problems. Groups led by Noble Energy Inc. have found fields off Israel and Cyprus, most of them in ultradeep water, that might contain 40 tcf of natural gas or more. New production promises to keep Israel, where gas demand is growing by as much as 17%/year, self-sufficient for years.

But future development will push gas deliverability beyond the needs of Israel and its immediate neighbors, with which relations are always touchy. Much new supply will have to be exported in some amount, somehow. While proposals for pipelines and LNG schemes have emerged, they all face problems related to economics or international relations—or both.

Strongly influential in the geopolitics of eastern Mediterranean gas development is Turkey, which also has rapidly growing requirements for natural gas as well as a developing role as a bridge for gas flowing between the Caspian Sea and Europe. Also like Israel, the country has dicey relations with some of its neighbors.

Emerging potential

Deepwater potential in the eastern Mediterranean became evident with the 2009 discoveries of deepwater Tamar gas field and smaller Dalit field.

For Israel, the start-up of Tamar production in March 2013 was especially timely. Output from offshore Noa and Mari-B fields, discovered in 1999-2000 by the Yam Tethys joint venture of Noble, Delek Drilling, and Delek affiliate Avner Oil & Gas Exploration was in late stages of decline. Delivery of Egyptian gas via the short El Arish-Ashkelon marine pipeline, which once filled 40% of Israel's gas needs, ceased in 2011 because of political disruptions in the supply country. Early last year, Israel was importing LNG to meet its gas needs.

Tamar, with a discovered resource estimated by Noble at 10 tcf, now produces an average 750 MMcfd of gas through a pipeline to the Mari-B platform. Peak deliverability is 1 bcfd. Noble plans to expand that to 1.5 bcfd next year, in part by adding compression at the Ashdod onshore terminal, which receives gas from Mari-B.

Tamar production will get a boost from the 2013 Tamar Southwest discovery, which is to be tied back to Tamar facilities for a production start next year. Noble estimates the gross mean resource of Tamar Southwest at 700 bcf.

In February, Noble signed agreements to sell 66 bcf of gas from Tamar field to two industrial customers in Jordan over 15 years. Deliveries will begin in 2016, when pipeline connections are complete. Gas supply has been a problem for Jordan since 2011, when the Egyptian uprising started a continuing series of disruptions to operation of the Arab Gas Pipeline, which carries gas to Jordan and Syria and serves Lebanon via a spur without transiting Israel.

Questions about exporting Israeli gas gained heft with the discovery in 2010 of Leviathan field, which like Tamar lies in more than 5,000 ft of water. With a discovered resource of 19 tcf, Leviathan promises to be able to yield far more gas than Israel and its neighbors need and to receive supplemental supply from several nearby discoveries, including the strategically important Aphrodite strike in Cypriot water.

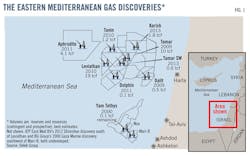

Fig. 1 shows eastern Mediterranean gas discoveries in which Delek and affiliates hold interests of varying size with Noble. Not shown is the undeveloped Shimshon discovery of 2012 made by a group led by ATP East Med BV. The operator is a unit of ATP Oil & Gas Corp., which entered bankruptcy not long after the discovery because of problems related to the 2010 Macondo blowout in the Gulf of Mexico. The Shimshon well, drilled to 14,445 ft subsea in 3,622 ft of water south of Leviathan and Tamar fields, cut 62 ft of gas pay.

Also not shown on Fig. 1 is a discovery called Gaza Marine made in 2000 by a group led by BG Group off Gaza under a license from the Palestinian Authority. Development has been blocked by Israeli jurisdictional objections and concern about the use of revenue from gas sales.

The discoveries off Israel, Cyprus, and the Palestinian Territory have aroused interest in other coastal countries. Turkey in November 2011 signed an agreement with Shell for exploration in the Mediterranean and in the southeastern part of the country. Lebanon, with territorial waters near some of the Israeli discoveries, passed a hydrocarbons law in 2010 and planned to open its first offshore licensing round last year but has delayed bidding three times because of political conflicts. Part of one of the blocks identified by Lebanon extends into a narrow, 330-sq-mile area of dispute with Israel. Licensing off Syria will be improbable as long as the country remains riven by civil war.

In a future exploratory project with potential to change the eastern Mediterranean play fundamentally, Noble plans in the first half of 2015 to drill a deeper pool test at Leviathan to 24,600 ft in 5,400 ft of water. The target: a Lower Cretaceous sandstone the operator considers oil-prone.

Export schemes

A full menu of schemes for exporting Eastern Mediterranean gas unfolded before anyone knew how much gas legally would be available for transport outside the region. The needed clarification came last year, when the Israeli High Court of Justice upheld a June decision by a committee of ministers capping exports at 40% of total reserves discovered off the country. The decision ended a political controversy centered on Israeli concern about long-term gas supply.

The new regime allows for balancing of share limits among fields and caps the exportable maximum for any single field at 75%. If resource volumes under current estimates are developed into reserves, 16 tcf would be available for export from offshore Israel and as much as 14.25 tcf from Leviathan field alone.

Export schemes proposed or discussed include these:

• LNG from a liquefaction plant on the Israeli coast, requiring a marine pipeline about 100 miles long to reach the probable site.

• LNG from a plant at Vasilikos, Cyprus, requiring a 125-mile pipeline.

• LNG from floating liquefaction facilities at Leviathan, Tamar, or Aphrodite field.

• A pipeline from the Leviathan-Tamar area to Turkey, a subsea distance of 250-280 miles.

• A pipeline from Leviathan-Tamar to Egypt, about 125 miles.

• A pipeline to Greece via Cyprus and Crete, with marine distances of 745-950 miles, depending on routing.

Developments in the latter half of 2013 and early this year will influence planning for the export of gas from eastern Mediterranean fields.

In October, Noble, after drilling and testing an Aphrodite appraisal well 4 miles east of the discovery, lowered the field's gross mean resource estimate to 5 tcf from the original 7 tcf. Noble said further appraisal would be needed for a full assessment. At the new level, an onshore Cypriot LNG project would need supplemental supply from Leviathan or other fields nearby.

And in February, Noble signed a nonbinding memorandum of understanding to make Woodside Petroleum a 25% partner in the Leviathan license as a way to bring LNG expertise to the project. The signing upgraded and changed an in-principal agreement signed in December 2012. Under the deal, still subject to regulatory and other approvals, Woodside would pay as much as $2.5 billion, plus contingencies based on future production and exploratory results, for a 25% interest conveyed by Noble and its current partners—Delek Drilling, Avner Oil Exploration, and Ratio Oil Exploration. Noble would remain operator of upstream activities, and Woodside would become operator of an LNG development.

Geopolitical complications

Among all the gas-export schemes under discussion, a pipeline from the deepwater fields to Turkey might seem to make the most economic sense if distance and markets were the only considerations. In the eastern Mediterranean region, though, geopolitical risks loom especially large.

Turkey, like Israel, has rapidly growing requirements for natural gas, nearly all of which it imports. Of about 1.5 tcf of gas imported in 2011, according to the US Energy Information Administration, most came from three pipeline suppliers: Russia 67%, Iran 19%, and Azerbaijan 9%.

Turkey also has aspirations to be a transit country for natural gas as important as it already is for oil. It moved strongly toward fulfillment of that goal last year when the consortium developing giant Shah Deniz gas-condensate field in the Caspian off Azerbaijan approved a second phase of investment, having earlier identified the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline as its favored transport link to Europe. That project and the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline will link with the Southern Caspian Pipeline across Azerbaijan and Georgia to form the Southern Energy Corridor (SEC)—a strategically important way for Caspian natural gas to move to Europe without crossing Russia.

Initially, after offtake of about 580 MMcfd under contract to Turkish buyers, the SEC will deliver slightly less than 1 bcfd to Europe. That's less than one sixth of the amount to be delivered by the planned South Stream Pipeline, which is to carry Russian gas across the Black Sea, including Turkish waters, to Europe. Turkish approval of South Stream transit of its offshore territory is widely seen as a concession to the country's need for cordial relations with its main gas supplier.

Gas from the Israeli fields would diversify Turkish import sourcing and ease concerns about expandability of the SEC's throughput capacity given Turkey's own growing gas needs. But Turkey's relations with Israel are in a state of uneasy repair after collapsing in May 2010 over the killing by Israeli military forces of nine people, eight of them Turkish, aboard the passenger ferry Mavi Marmora. That vessel and several others were carrying activists thought to be testing an Israeli blockade of Gaza during a period of high tension. The Israeli government has apologized for the killings, and the governments of both countries have made unsteady progress toward restoration of diplomatic relations.

Even if Turkey and Israel solve their diplomatic problems, a pipeline from the deepwater Israeli fields to Turkey faces political and security risks that at least would complicate financing. It also would require the cooperation of Cyprus, which remains in conflict, albeit relaxing, with Turkey.

Turkey and Cyprus

Tension in Cyprus predates the island-nation's independence from the UK in 1960, before which Greek Cypriots had advocated unification with Greece while Turkish Cypriots sought partition. The legacy of this sometimes-violent struggle is a de facto division of the island into a Turkish north and Greek south and the longstanding presence of a United Nations peacekeeping force.

Officially, in the view of all countries except Turkey, the Republic of Cyprus governs the entire island. Alone among nations, Turkey views the northern part of the island as the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. The UN in 2008 began working toward a negotiated settlement between Turkish and Greek Cypriots that would make the island a two-part federation. Negotiations stalled in 2012 but resumed last February.

Lingering disagreements over the rights of Greek and Turkish Cypriots and over maritime borders unsettle the outlook for offshore oil and gas development.

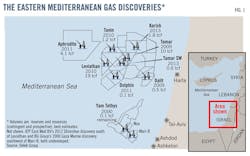

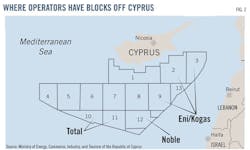

After Noble and partners made the deepwater Aphrodite gas discovery on Block 12, the government of Cyprus held a second licensing round offering a dozen other blocks (Fig. 2). Total won licenses to two of them, and a combine of Eni and Korea Gas Corp. won three.

Turkish Cypriots object to what they see as Greek Cypriot unilateralism in these initiatives and argue that agreements governing oil and gas work should involve them and be made only after a settlement establishing federal governance. Turkey, in support of the Turkish Cypriot position, has used warships to monitor offshore oil and gas activity.

According to the Greek Cypriot position, issues related to energy should be subject to international law, which it sees as supporting its actions, rather than UN negotiations. This position agrees that Turkish Cypriots should share in the economic benefits of oil and gas work, but some Greek Cypriot politicians argue that, in the absence of a settlement of the north-south conflict, Turkish Cypriots have no claim to influence over how resources should be developed.

In the conflict over maritime borders, Turkey claims pieces of what Cyprus identifies as its Blocks 1, 4, 5, 6, and 7. The Turkish Cypriots have proposed to allocate their own blocks for Cyprus as a whole, with some of them overlapping Cypriot Blocks 1, 2, 3, 8, 9, 12, and 13.

The maritime-boundary and partition issues were overshadowed for several months last year by a financial crisis that began in March and threatened the Cypriot economy with collapse. The European Union and International Monetary Fund in April 2013 provided a 3-year bailout package worth €10 billion.

Stabilization of the Cypriot economy removes a distraction from the diplomacy required for the removal of one impediment to full exploitation of the eastern Mediterranean's gas—and maybe oil—potential. Other impediments remain. Diplomacy will be needed for them, too.

Acknowledgment

Many insights in this article emerged in a workshop, Energizing Peace: Security Enhancement Opportunities of Eastern Mediterranean Energy Resource Development, in which the author participated Mar. 13-16 in Istanbul. The US government's Near East South Asia Center for Strategic Studies conducted the event under Chatham House rules, which allow reporting without attribution or identification of participants.

About the Author

Bob Tippee

Editor

Bob Tippee has been chief editor of Oil & Gas Journal since January 1999 and a member of the Journal staff since October 1977. Before joining the magazine, he worked as a reporter at the Tulsa World and served for four years as an officer in the US Air Force. A native of St. Louis, he holds a degree in journalism from the University of Tulsa.